In the last issue of The New Republic, Lawrence Lessig published the unfortunately titled article “Against Transparency.” In it he criticizes what he calls the “naked transparency movement.”* The article has drawn several responses, with Ellen Miller and Michael Klein’s being the best and most direct. I’d like to offer a libertarian perspective.

In the last issue of The New Republic, Lawrence Lessig published the unfortunately titled article “Against Transparency.” In it he criticizes what he calls the “naked transparency movement.”* The article has drawn several responses, with Ellen Miller and Michael Klein’s being the best and most direct. I’d like to offer a libertarian perspective.

Lessig’s thesis is that the revolution in government transparency that modern information technology makes possible is a double-edged sword because what it uncovers is simply the general corruptibility of government–and he speaks of Congress in particular. Tools like MAPLight.org show that there is a strong correlation between campaign contributions and legislative votes. Some of these may indeed be corrupt bargains, and some may not. But the fact is that “the contributions are corrupting the reputation of Congress, because they raise the question of whether the member acted to track good sense or campaign dollars.”

Because citizens are prone to rational ignorance (although Lessig insists on relabeling the concept “lack of attention-span”), they will not investigate individual votes or other actions very deeply, and they will unfairly ascribe a certain susceptibility to influence to all in Congress. As a result, the naked transparency movement won’t inspire reform, but instead “will simply push any faith in our political system over the cliff.” Lessig writes:

At this time the judgment that Washington is all about money is so wide and so deep that among all the possible reasons to explain something puzzling, money is the first, and most likely the last, explanation that will be given. It sets the default against which anything different must fight. And this default, this unexamined assumption of causality, will only be reinforced by the naked transparency movement and its correlations. What we believe will be confirmed, again and again.

His solution? “A system of publicly funded elections would make it impossible to suggest that the reason some member of Congress voted the way he voted was because of money.” Take the money out of politics, Lessig argues, and you also take away the cynicism that forestalls change.

Lessig’s solution reminds me of airline regulation in the 60s and 70s. Prices where set by government, so airlines were forced to compete on other margins. First came the elaborate meals, then the in-flight bar lounges and later piano bars, and then “the musicians, magicians, wine-tasters, and Playboy bunnies.”

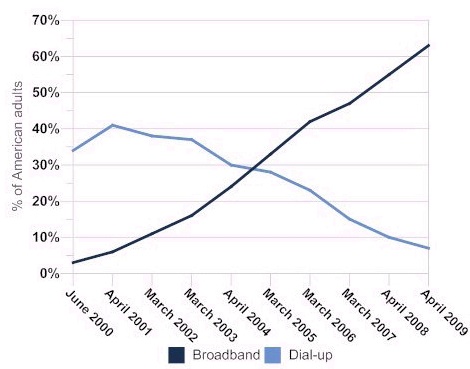

One reason might be that it’s hard to imagine the growth curve for Internet adoption being a whole lot steeper than it is. According to

One reason might be that it’s hard to imagine the growth curve for Internet adoption being a whole lot steeper than it is. According to

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

More on the FCC’s e-Government Transparency Efforts: ECFS, RSS, Social Media & Setting Priorities

by Berin Szoka on September 11, 2009 · 12 comments

I vented my frustration earlier today with the FCC’s failure to make comments it receives easily accessible to the public—which means, more than anything, making them full-text searchable. This may seem like Inside Baseball to many, but it’s not. It’s a failure of the democratic process, a waste of taxpayer dollars, and a testimony to the general incompetence of bureaucracies, regardless of who’s running them. It denies the public an easy way to follow what goes on inside Washington, while essentially subsidizing law firms who get to bill clients for having paralegals or junior associates do things that existing web technology makes completely unnecessary—like reading through every comment in a document (at the rate of hundreds of dollars per hour) instead of just looking for keywords in a full-text search.

Later in the day the FCC announced:

I’m thrilled about the RSS feeds, which go a long way in letting all Americans know what the FCC does, supposedly in the “public interest.” Still, I can’t help but note that the FCC waited until after a huge discussion about whether RSS is dead to finally start using RSS in a serious way—fully a decade after the birth of the RSS standard. Better late than never, I suppose.

FCC Connect is also good news: once you have an RSS feed, there’s really no reason not to pipe that feed into as many platforms as possible—which is precisely why RSS isn’t dead, even if most people will never use an RSS reader.

But I’m less thrilled about the crowdsourcing platform. Continue reading →