I’m finishing up Stanford Law School professor Lawrence Lessig’s latest book, Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy and wanted to make a brief comment about his call for a “simple blanket license” to solve online music piracy.

I’m finishing up Stanford Law School professor Lawrence Lessig’s latest book, Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy and wanted to make a brief comment about his call for a “simple blanket license” to solve online music piracy.

Overall, I thought Prof. Lessig made a good case regarding the benefits of “remix culture” and why copyright law should leave breathing room for the various derivative works of amateur creators. On the other hand, Lessig still too often blurs remix culture with “ripoff culture” (i.e., those who aren’t out to create anything new but instead just take something without paying a penny for it).

To solve that latter problem, Lessig again endorses a proposal that William Fisher, Electronic Frontier Foundation, and others have made for collective licensing of all online music, but he fails to drill down into the devilish details. He says, for example, that “by authorizing a simple blanket licensing procedure, whereby users could, for a low fee, buy the right to freely file-share” we could “decriminalize file sharing.” (p. 271)

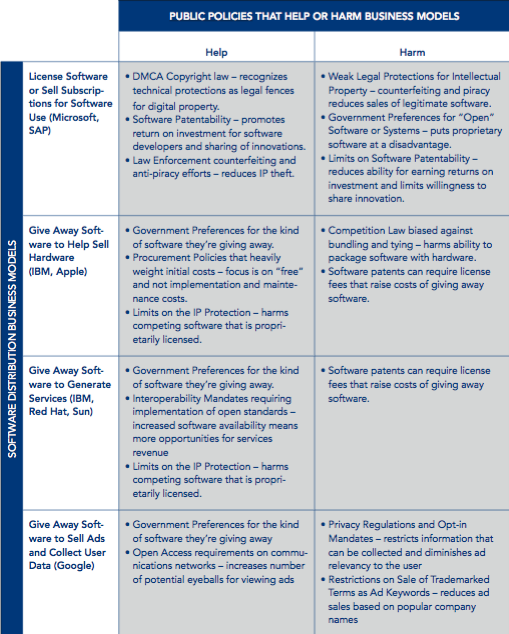

I respect the fact that Lessig is at least acknowledging a problem exists and proposing a solution to it, but the collective licensing approach will be anything but “simple” in practice. As I have pointed out here before, collective licensing proposals and efforts almost always become compulsory in practice. They inevitably involve government mandates to determine (1) who pays in, (2) how much they pay in, as well as (3) how much gets paid out and, (4) who gets the money.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.