Slashdot user “flyingsquid” suggests why Blizzard has had such a winning streak in federal copyright cases:

You, know, this could just be a coincidence, but a couple of weeks ago I was in Northrend and I ran into an orc named “JudgeCampbell”. He had some pretty sweet weapons and armor he was showing off, including a Judicial Robe of Invicibility and a Judge’s Battle Gavel of The Dragon, which did an unreal amount of damage. Also, he had all these really powerful spells I’d never even heard of before, such as “Contempt of Court” and “Summon Bailiff”. To top it all off, he had like 200,000 gold. I asked where he’d gotten all this stuff and he said he’d just “found it all in some dungeon”. It sounded kind of fishy to me, but I didn’t think anything much of it at the time.

I demand an investigation!

The Isle of Man may soon implement a “blanket license” whereby Manx broadband users could download as much music as they like in exchange for paying a “fee” (also known as a “tax,” since this would be non-optional) to their ISP that would supposedly be as low as $1.38/month. The Manx proposal sounds a lot like how SoundExchange administers a blanket license in the U.S. for web-casting of copyrighted music:

The Isle of Man may soon implement a “blanket license” whereby Manx broadband users could download as much music as they like in exchange for paying a “fee” (also known as a “tax,” since this would be non-optional) to their ISP that would supposedly be as low as $1.38/month. The Manx proposal sounds a lot like how SoundExchange administers a blanket license in the U.S. for web-casting of copyrighted music:

the money collected by the Internet providers would be sent to a special agency that would distribute the proceeds to the copyright owners, including the record labels and music publishers. They would receive payments based on how often their music was downloaded or streamed over the Internet, as they now do in many countries when it is performed live or on the radio.

As Adam Thierer has noted, Larry Lessig has endorsed at least a voluntary version of this idea, but Adam has raised a number of tough questions: Continue reading →

I used to have a (semi-crazy) uncle who typically began conversations with lame jokes or bad riddles. This sounds like one he might have used had he lived long enough: What do Thomas Jefferson, a moose, and cyberspace have in common?

I used to have a (semi-crazy) uncle who typically began conversations with lame jokes or bad riddles. This sounds like one he might have used had he lived long enough: What do Thomas Jefferson, a moose, and cyberspace have in common?

The answer to that question can be found in a new book, In Search of Jefferson’s Moose: Notes on the State of Cyberspace, by David G. Post, a Professor of Law at Temple University. Post, who teaches IP and cyberspace law at Temple, is widely regarded as one of the intellectual fathers of the “Internet exceptionalist” school of thinking about cyberlaw. Basically, Post sees this place we call “cyberspace” as something truly new, unique, and potentially worthy of some special consideration, or even somewhat different ground rules than we apply in meatspace. More on that in a bit.

[Full disclosure: Post’s work was quite influential on my own thinking during the late 1990s, so much so that when I joined the Cato Institute in 2000, one of the first things I did was invite David to become an adjunct scholar with Cato. He graciously accepted and remains a Cato adjunct scholar today. Incidentally, Cato is hosting a book forum for him on February 4th that I encourage you to attend or watch online. Anyway, it’s always difficult to be perfectly objective when you know and admire someone, but I will try to do so here.]

Post’s book is essentially an extended love letter — to both cyberspace and Jefferson. Problem is, as Post even admits at the end, it’s tough to know which subject this book is suppose to teach us more about. The book loses focus at times — especially in the first 100 pages — as Post meanders between historical tidbits of Jefferson’s life and thinking and what it all means for cyberspace. But the early focus is on TJ. Thus, those who pick up the book expecting to be immediately immersed in cyber-policy discussions may be a bit disappointed at first. As a fellow Jefferson fanatic, however, I found all this history terrifically entertaining, whether it was the story of Jefferson’s Plow and his other agricultural inventions and insights, TJ’s unique interest in science (including cryptography), or that big moose of his.

OK, so what’s the deal with the moose? When TJ was serving as a minister to France in in the late 1780s, at considerable expense to himself, he had the complete skeleton, skin and horns of a massive American moose shipped to the lobby of his Paris hotel. Basically, Jefferson wanted to make a bold statement to his French hosts about this New World he came from and wake them up to the fact that some very exciting things were happening over there that they should be paying attention to. That’s one hell of way to make a statement!

My piece about the U.S. Chamber of Commerce event last Friday on U.S. intellectual property attachés giving a report, and taking a hard line, on the enforcement of U.S. intellectual property, overseas, is now live on ip-watch.org.

Here’s the first couple of paragraphs:

WASHINGTON, DC – Nations ranging from Brazil to Brunei to Russia are failing to properly protect the intellectual property assets of US companies and others, and international organisations are not doing enough to stop it, seven IP attachés to the US Foreign and Commercial Service lamented recently.

Meanwhile, an industry group issued detailed recommendations for the incoming Obama administration’s changes to the US Patent and Trademark Office.

The problems in other nations extend from Brazil’s failure to issue patents for commercially significant inventions by US inventors, to an almost-complete piracy-based economy in Brunei, to an only-modest drop in the rate of Russian piracy from 65 percent to 58 percent.

The attachés, speaking at an event organised by the US Chamber of Commerce and its recently beefed-up Global Intellectual Property Center (GIPC), blasted the record of familiar intellectual property trouble zones like Brunei, Thailand and Russia.

But the problems extend to the attitudes and omissions of major trading partners like Brazil, India and even well-developed European nations, said the attachés.

[more at http://www.ip-watch.org/weblog/index.php?p=1387….]

“Damn their lies and trust your eyes. Dig every kind of fox!” I here sing one for the freedom to mix it up as you and your honey alone see fit:

“Hapa” means “mixed race” in Hawaiian. Skin-tone mash ups have profoundly enriched my life, first with the Honolulu Hapa herself and then with our own little hapas. Honolulu Hapa celebrates coloring across the lines, knocks racism, and gives a shout-out to Loving v. Virginia, 88 U.S. 1 (1967)—the case where the U.S. Supreme Court struck down anti-miscegenation laws as unconstitutional restraints on personal liberty.

As with the prior four songs I’ve posted in this recent series (Take Up the Flame, Sensible Khakis, Nice to Be Wanted, and Hello, Jonah,), Honolulu Hapa comes with a Creative Commons license that allows pretty liberal use by all but commercial licensees, who have to pay a tithe to one of my favorite causes. Honolulu Hapa aims to help Creative Commons, an organization that helps all of us to mix—and remix—it up. Unlike those other songs, however, Honolulu Hapa adds a special ‘unrestricted use” term effective on June 12, Loving Day.

With Honolulu Hapa, I conclude my recent series of freedom-loving music videos. Like it or not, though, I’ve got more music-making plans. Next, I’ll record some good studio versions of those (and perhaps some other) songs. Eventually, I’d like to release a fundraising CD, one that might help out some good causes. Silly? Yeah, I guess so. But it does add another data point in support of my hypothesis: Freedom has more fun.

[Crossposted at Agoraphilia and Technology Liberation Front.]

I’m more sympathetic to EFF-style voluntary collective licensing than Mike Masnick is, but I have to say that the case he makes here is pretty compelling. I think this is really the key point:

What you’re doing is setting up a big, centrally planned and operated bureau of music, that officially determines the business model of the recording industry, figures out who gets paid, collects the money and pays some money out. The same record industry that has fought so hard against any innovation remains in charge and will have tremendous sway in setting the “rules.” The plan leaves no room for creativity. It leaves no room for innovation. It’s basically picking the only business model and encoding it in stone.

Oh, and did we mention it’s only for music? Next we’ll have to create another huge bureaucracy and “license” for movies. And for television. And, what about non-television, non-movie video content? Surely the Star Wars kid deserves his cut? And, newspapers? Can’t forget the newspapers. After all, they need the money, so we might as well add a license for news. And, if that’s going to happen, then certainly us bloggers should get our cut as well. Everyone, line right up!

This is a bad plan that will create a nightmare bureaucracy while making people pay a lot more, without doing much to actually reward musicians.

The key thing to remember here is that there’s nothing special about the music industry. The record labels have been hardest hit by peer-to-peer file sharing, but their fundamental problem actually has very little to do with BitTorrent. Rather, their problem is the same problem that’s befallen the newspaper industry: the marginal cost of content has dropped to zero, and so the price of content is also going to be driven to zero sooner or later. The only thing that’s different about the music industry is that BitTorrent has sped the process up: prices have dropped faster because in addition to competing with new entrants, labels are also “competing” with pirated copies of their own content.

But that’s just a transitory phenomenon. The long-run trend is that there’s going to be a much larger eco-system of free music, just as the blogosphere is a large eco-system of free punditry. And in that environment, business models that rely on content being expensive are doomed, just as Craig’s List doomed newspapers built on the premise of expensive classified advertising. I think Mike is probably right that implementing a de facto music tax would have the effect of cementing in place an increasingly anachronistic industry structure.

With that said, a music tax would have some short-term benefits. An effective collective licensing scheme would create a much more fertile environment for entrepreneurs to build innovative technologies on top of peer-to-peer technologies, so maybe a music tax is a price worth paying for the benefits of a peer-to-peer friendly legal environment. But before I get behind the idea, I’d want to see a clear explanation of how such an agreement would apply to other types of media, and what the long-term evolution of the industry would be.

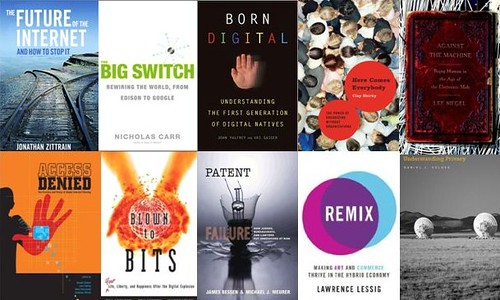

It’s been a big year for tech policy books. Several important titles were released in 2008 that offer interesting perspectives about the future of the Internet and the impact digital technologies are having on our lives, culture, and economy. Back in September, I compared some of the most popular technology policy books of the past five years and tried to group them into two camps: “Internet optimists” vs. “Internet pessimists.” That post generated a great deal of discussion and I plan on expanding it into a longer article soon. In this post, however, I will merely list what I regard as the most important technology policy books of the past year.

What qualifies as an “important” tech policy book? Basically, it’s a title that many people in this field are currently discussing and that we will likely be talking about for many years to come. I want to make it clear, however, that merely because a book appears on this list it does not necessarily mean I agree with everything said in it. In fact, I found much with which to disagree in my picks for the two most important books of 2008, as well as many of the other books on the list. [Moreover, after reading all these books, I am more convinced than ever that libertarians are badly losing the intellectual battle of ideas over Internet issues and digital technology policy. There’s just very few people defending a “Hands-Off-the-Net” approach anymore. But that’s a subject for another day!]

Another caveat: Narrowly focused titles lose a few points on my list. For example, as was the case in past years, a number of important IP-related books have come out this year. If a book deals exclusively with copyright or patent issues, it does not exactly qualify as the same sort of “tech policy book” as other titles found on this list since it is a narrow exploration of just one set of issues that have a bearing on digital technology policy. The same could be said of a book that deals exclusively with privacy policy, like Solove’s Understanding Privacy. It’s an important book with implications for the future of tech policy, but I demoted it a bit because of its narrow focus.

With those caveats in mind, here are my Top 10 Most Important Tech Policy Books of 2008 (and please let me know about your picks for book of the year):

TLF reader Timon makes a really good point about the choice between authenticated and unauthenticated networks:

Lawyers are trained to view complex questions and come up with balanced approaches to them — ie “balancing” privacy with police prerogatives and subpoenas. The technical world is rather the opposite; no matter how complex, an encryption algorithm, for example, either is or is not secure, and as soon as it isn’t it really isn’t. In a legal class it makes for good discussion to say, on the one hand, IP addresses should be private, except when they are used to commit a crime. In direct technical terms what this amounts to is a full surveillance state that is then ruled by court procedure: the law requires someone keep records of all mail or other communications, and then provide them to the authorities when told to. While under law there could be a protection of privacy, in technical terms there is absolutely no privacy, except that which the state decides to concede, the information it declines to look at but which is permanently stored on its orders and available for its inspection. It may seem to you that some people are just unwilling to split the difference and be reasonable, but it really is the case that where lawyers see gray others see black and white, with good technical reasons. There is no way to enforce copyright, for example, and allow anonymous speech online, as you seem to be picking up on. That is not because we are unwilling to be fair, it is a characteristic of information.

Demanding that government limit itself is never a very effective strategy, because if government can do something, it probably will. It’s far more effective to limit government by design. The Internet’s open architecture is, among other things, an important limitation on the government’s surveillance power. Precisely because there are so many ways to get on the Internet without authentication, the government has to do a lot of extra work if it wants to spy on people. For those of us who care about civil liberties, this is a feature, not a bug.

Of course, freedom isn’t free. The same characteristics that make the Internet resistant to a surveillance state also make it harder to enforce copyright, laws against child pornography, etc. This is unfortunate, but I don’t think it’s so unfortunate that we should be willing to toss out the liberty-enhancing benefits of the open Internet. Because as Timon says, there isn’t a middle ground here. Either ISPs have a reliable way to identify their users or they don’t. And if we require them to have this ability for what we regard as good reasons, it’s inevitable that the government will use that same power for bad purposes down the road.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.