The Economist has an interesting overview of Rupert Murdoch’s purchase of Dow Jones this week. The piece, “Murdoch Gets His Trophy,” highlights the negotiating skill exhibited by Murdoch in the whole affair, from the timing of the offer to his spot-on reading of the Bancroft family’s internal politics.

That said, the magazine questions the wisdom of the purchase. It’s unlikely, The Economist argues, that Dow Jones will provide to New Corporation anything near the $5 billion Rupert paid.

“Which is why,” it says,” some News Corporation shareholders suspect that they are just excuses, and that Mr Murdoch has put his longtime desire to own the one of the world’s great newspapers before any serious consideration of value for money.”

Wouldn’t it be ironic — after all the hand-wringing over the undue power the acquisition supposedly gives New Corporation — if the biggest loser turns out to be News Corporation itself?

Today, the Well Connected Project of the Center for Public Integrity is excited to launch an issue portal jointly with Congresspedia. This issue portal is a wiki, like Wikipedia, creating a collection of articles on telecom, media and technology policy, in a single location. Anyone can read, write and edit these articles.

This issue portal builds on the great telecom and technology reporting done by the members of the Well Connected Project staff. This venture into collaborative journalism is a first for our project. It adds a new element to our investigative journalism endeavor. First of all, we have the Media Tracker, a free database of more than five million records that tells you who owns the media where you live by typing in you ZIP code. If we win our lawsuit against the FCC, we’ll also include company-specific broadband information in the Media Tracker.

Second, our blog features dozens of quick-turnaround stories on the hottest topics in telecom and media policy. Recent stories have broken news on the battle over 700 Megahertz, on the lobbying over the proposed XM-Sirius satellite radio merger, and also over copyright controls on electronic devices. We also do investigative reports – like this one about Sam Zell, the new owner of Tribune Co. – that build on the data that is freely available in Media Tracker.

Now, with the addition of this Congresspedia wiki, our project aims to incorporate citizen-journalism on key public policy issues near and dear to the blogosphere. These are issues like Broadband availability, Digital copyright, Digital television, Regulating media content, and Spectrum are at the core of what techies care about in Washington. We hope you will add others articles, too. In fact, I’ve already started my own wish list: articles about Patent overhaul legislation, Media ownership, the Universal Service Fund, and Video franchising. Our reporters can summarize these issues and debates, but so can you.

Take a crack at them!

Continue reading →

WASHINGTON, July 3, 2007 – The Federal Trade Commission intends to monitor the information that telecom and cable companies provide about high-speed Internet service in the service plans they offer to customers, according to a report issued last week by the agency.

The FTC asserts in the report, released on June 27, that since it has jurisdiction over matters involving consumer protection, it “will continue to enforce the consumer protection laws in the area of broadband access.”

Continue reading →

How do the direct and indirect trade barriers of some nations unfairly harm the ability of foreign (particularly American) IT companies to monetize digital innovations and distribute intellectual assets globally? That’s the focus of a new paper from Rob Atkinson and Julie Hedlund at ITIF, entitled The Rise of the New Mercantilists: Unfair Trade Practices in the Innovation Economy.

Today’s innovations have much shorter life-cycles, so companies need

broader, faster market distribution in order to earn returns on

innovation–money they invest in tomorrow’s innovations. These companies seek

sales and licensing markets all across our “flat world.” The ITIF report discusses how it’s not your father’s form of protectionism anymore (such as tariffs and direct subsidies). Companies also face protectionist trade barriers in the forms of lax enforcement of intellectual property piracy and counterfeiting, disparate competition regulations, government preferences and standards manipulation.

Now here’s the crux of the question: is this a new

form of protectionism – what my colleague Steve DelBianco and I call “Protectionism 2.0”? Or are these more subtle forms of trade barriers the result of legitimate public policy goals? Probably a bit of both, but one has to ask – if Microsoft were a German company would it be facing the full wrath of competition regulators? Or if Apple were Dutch, or Norwegian, or French – would it be scrutinized by regulators in those countries eager to break the link between iTunes and iPod?

My former boss David Boaz has a great post lamenting Google’s decision to dramatically expand its political muscle:

Google’s brilliant staff are now spending some of their intellect thinking up ways to sic the government on Microsoft, which is once again forced to give consumers a less useful product in order to stave off further regulation. The Post’s previous story on Google’s complaint called it ”allegations by Google that Microsoft’s new operating system unfairly disadvantages competitors.”

Bingo! That’s what antitrust law is really about–not protecting consumers, or protecting competition, but protecting competitors. Competitors should go produce a better product in the marketplace, but antitrust law sometimes gives them an easier option–asking the government to hobble their more successful competitor.

Recall the famous decision of Judge Learned Hand in the 1945 Alcoa antitrust decision. Alcoa, he wrote, “insists that it never excluded competitors; but we can think of no more effective exclusion than progressively to embrace each new opportunity as it opened, and to face every newcomer with new capacity already geared into a great organization, having the advantage of experience, trade connection and the elite of personnel.” In other words, Alcoa’s very skill at meeting consumers’ needs was the rope with which it was hanged.

I look forward to more competition between Microsoft and Google–and the next innovative company–to bring more useful products to market. But I’m saddened to realize that the most important factor in America’s economic future — in raising everyone’s standard of living — is not land, or money, or computers; it’s human talent. And some part of the human talent at another of America’s most dynamic companies is now being diverted from productive activity to protecting the company from political predation and even to engaging in a little predation of its own. The parasite economy has sucked in another productive enterprise, and we’ll all be poorer for it.

I regard Google as the good guys on at least some of the issues their lobbyists are likely to focus on. But the broader point is spot on: these lobbying battles are a massive waste of talent. The more power Washington has over the technology industry, the more money companies will spend ensuring that that power is used to help, rather than hurt them. This is one of the reasons it’s a good idea to think twice before enacting legislation that will expand government power.

Earlier this week the NY Times reported that Google filed a complaint with the Department of Justice about Microsoft’s desktop search. At a time when Google is under scrutiny in the EU for privacy practices, censorship in China, and has potential antitrust issues of its own with the recent DoubleClick acquisition, this complaint is politically precarious.

But the complaint hits on a broader public policy point: will antitrust regulation put the heat on tech companies that innovate by integrating?

That’s the subject of my new paper along with co-author

Steve DelBianco. In Consumer Demand Drives Innovation and Integration in Desktop Computing, we examine the competition policy concerns raised by the

on-demand desktop, and the danger that overzealous regulators could constrain

the future of Web2.0.

Feature integration is an essential way to improve products

and motivate existing consumers to upgrade. Traditional desktop vendors like

Microsoft and Apple usually spend several years integrating new features into

major releases of their operating systems and applications. Even a core Linux distribution like Debian

manages only about one release each year. Consumers often prefer a bundled

product that provides more value for the money, and the software industry

typically responds by combining services in a suite of applications.

Continue reading →

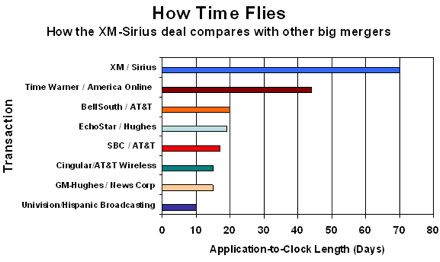

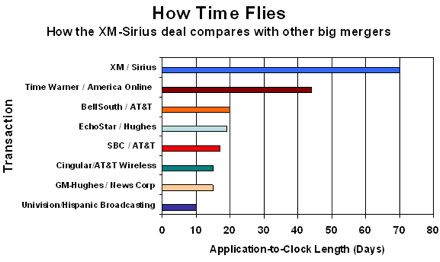

The FCC is famous, even among its regulatory bureaucracy peers, for its mollusk-like pace of action. Not that it hasn’t tried to improve. For instance, a few years ago it put into place a 180-day “shot clock” for reviewing mergers — giving itself six months to give an up-or-down decision on transactions. It was a nice idea. It came with a few loopholes, however — for instance, nothing says when the vaunted “shot clock” must begin.

(chart from Engadget, numbers as of May 31).

The folks at Sirius and XM Radio have learned this the hard way. Last Friday, the FCC started its 180-day clock — launching a proceeding to review their merger, 78 (seventy-eight) days after the firms submitted their merger plans. That’s a record.

No official word on why the mergers was left hanging so long. Its certainly been a controversial deal — surrounded by quite a bit of uncertainty (bizarrely, even on whether the FCC has a rule banning the merger). But that hardly justifies a 78-day delay: its the controversial and uncertain deals that need a deadline, not the easy ones.

Anyway, for now, the clock is ticking, giving the FCC some 176 more days to decide. Unless it decides to stop the clock again.

“We suck less,” said Sirius CEO Mel Karmazin to shareholders yesterday at the firm’s annual meeting, comparing the firms dismal performance to that of XM Radio. While perhaps better than sucking more, the statement could not have cheered investors.

Satellite radio investors looking for optimism, would have been better off reading a letter from Senate antitrust subcommittee chairman Herb Kohl, sent Wednesday to the FCC and to the Justice Department. The proposed XM-Sirius merger, he said should be rejected, since there aren’t any competitors to the two. Old-fashioned terrestrial radio, he wrote, just can’t compete with satellite’s “tremendous variety” of formats, “far superior sound quality” all provided on a commercial-free basis. Kohl similarly dismisses Internet radio and MP3 players, finding they also provide no alternatives for consumers.

It must have come as a surprise to satellite investors — who have never seen a profit — that they hold such a stranglehold on the market. It would no doubt be a surprise to consumers as well – hundreds of millions of whom do not subscribe to either satellite service, along with countless others who use iPods instead of radio. These consumers have no alternative to satellite radio service — according to Kohl — they just don’t know it yet.

Unfortunately for any shareholders hoping to start raking in monopoly profits, Kohl is wrong. There is no satellite stranglehold on radio, and no lack of competitors. And that competition will continue — or even increase — if the proposed merger takes place. For U.S. consumers, that doesn’t suck at all.

The EU continues to issue what one hopes are wild threats against Microsoft. Now EU antitrust authorities have revived the possibility of “structural remedies,” that is, breaking Microsoft up. This apparently because Microsoft is seen to be resisting compliance with earlier orders.

Interesting. What is the theory behind this? The focus of antitrust law is supposed to be consumer welfare (not, say, competitor welfare). So the earlier commission orders were supposed

Continue reading →

Say what you want about Rupert Murdoch, but the man certainly knows how to make news. His bid for Dow Jones two days ago – despite being initially rejected by Dow Jones’ controlling family — is still reverberating through media, financial, and political circles.

From the start, the proposed deal came under a hail of criticism. That is in itself unsurprising. Murdoch is so unpopular that any acquisition would be roundly condemned. If he tried to buy a ham sandwich for lunch that would be condemned.

But isn’t this a debate over media concentration, not just Murdoch? Anti-media consolidation activists, of course, have trotted out all the usual concentration-of-power arguments. The media market has been called a monopoly, an oligopoly, and every other type of poly that can be found in Greek dictionaries. But these arguments have sounded even more hollow than usual. There’s little overlap between Dow Jones and Murdoch’s News Corporation. Dow Jones owns newspapers – mostly small ones and one really big one – but has no broadcast holdings. News Corporation owns TV stations but only one newspaper in the U.S.

Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.