Yesterday, NetChoice joined the Center for Democracy & Technology and the Maine Civil Liberties Union (and PFF, who submitted written testimony) before the Maine legislature to oppose a bill that would restrict how health-related products can me marketed to minors under age 17.

The bill, LD 1677, is a repeal and replacement for current law passed last year that was strongly opposed by the online industry. As I previously blogged, NetChoice was a lead plaintiff in last year’s lawsuit to enjoin the law. Though well intentioned, this law was overly-broad and wrought with constitutional concerns. As a result, Attorney General Mills agreed not to enforce the statute. In October last year, NetChoice joined others in testifying before Maine Joint Standing Committee on the Judiciary regarding this law. In short, the conclusion of all parties involved was that the current legislation could not stand and that the legislature should move to quickly repeal.

So we all arrived in Augusta, ready for the next round – after all, this bill is #9 on the NetChoice iAWFUL list! But when we arrived, we were treated to a surprise amendment from the bill sponsor and this became the focus for discussion and testimony. Here’s the amended prohibition:

A person may not knowingly collect and use personal information collected on the Internet from a minor residing in this State for the purposes of pharmaceutical marketing prescription drugs to that minor, unless the minor specifically requests that information about the prescription drug be provided to them

John Morris at CDT gave great testimony and generally welcomed the amendment. However, he cautioned the committee that it should make sure that website intermediaries would not have liability for merely displaying ads. Continue reading →

Today’s The Wall Street Journal Europe published an editorial that Alberto Mingardi of Istituto Bruno Leoni and I penned about the competition complaints brought against Google in Europe.

If policy makers set the terms in a primitive year like 2010, nobody will have to respond to Google.

By WAYNE CREWS AND ALBERTO MINGARDI

Google isn’t a monopoly now, but the more it tries to become one, the better it will be for us all. Competition works in this way: Capitalist enterprises strive to gain in profits and market share. In turn, competitors are forced to respond by trying to improve their offerings. Innovation is the healthy output of this competitive game. The European Commission, while pondering complaints against the Internet search giant, might consider this point.

Google has been challenged by a German, a British, and a French Web site, for its dominant position in the market for Web search and online advertisement. The U.S. search engine is said to be imposing difficult terms and conditions on competitors and partners, who are now calling regulators into action. Google’s search algorithm is accused of being “biased” by business partners and competing publishers alike.

Before resorting to the old commandments of antitrust, we should consider that the Internet world is still largely impervious and unknown to anybody—including regulators. We are in terra incognita, and nobody knows the likely evolution of the market. But one thing is for sure: Online search can’t evolve properly if it’s improperly regulated—no matter the stage of evolution.

Continue reading →

Congress gets dinged a lot for slowing down innovation, but sometimes that is just what the doctor ordered. Thirty-five years ago, a Democratically controlled Congress passed the Magnuson-Moss Act in an attempt to check a hyperactive FTC.

Congress gets dinged a lot for slowing down innovation, but sometimes that is just what the doctor ordered. Thirty-five years ago, a Democratically controlled Congress passed the Magnuson-Moss Act in an attempt to check a hyperactive FTC.

Like a kid set loose in a candy store, the FTC at the time had gone on a binge of overreaching and harmful regulation. The core enabler of this action is the exceptionally broad mandate bestowed on the agency to regulate all “unfair” consumer activity. Unlike regulating the structural stability of bridges or safety in food, “fairness” is a subjective concept.

Congress’ prudent action to place special restrictions on FTC rulemaking [15 U.S.C. Sect. 57a(b)(2)(A)] was in direct response to the agency’s overreach and regulation of activities that would have included advertising children’s products – in essence, acting like a kid in a candy store. Magnuson-Moss was the equivalent of putting the candy behind the counter, providing Congress and courts control over how much candy was appropriate.

Now, 35 years later, the FTC has that ‘unfairness feeling’ again. In a NY Times interview last month, FTC Chairman Jon Leibowitz signaled his intent to change standard marketing tactics of disclosure and opt-out, by requiring users to opt-In for collection of information for targeting ads. They are concerned about what’s “fair” in advertising, but we know that low rates of opt-in will reduce ad revenue. If the change were put into effect, free online services might have to charge a “fare” to users.

At the same time, the FTC is seeking to shed what the Chair called “medieval restrictions” on its rulemaking powers. A change that would allow the FTC to move quickly to require opt-in. Taken together, these threats to online services and e-commerce are #1 on the NetChoice 2010 iAWFUL list. Continue reading →

By Adam Thierer & Berin Szoka

Progress & Freedom Foundation Progress Snapshot No. 6.5, Feb 2010 [.pdf]

Advertising is increasingly under attack in Washington. In fact, we’re busy finishing up a paper with the working title: “The New Assault on Advertising: What it Means for the Future of Media & Culture.” Among other things, the paper inventories the many ways in which policymakers in Washington and elsewhere are stepping up regulation of commercial advertising and marketing efforts-and highlights the common themes that unite them. Unfortunately, the report is already over 50 pages long and we keep finding new threats to discuss!

Advertising is increasingly under attack in Washington. In fact, we’re busy finishing up a paper with the working title: “The New Assault on Advertising: What it Means for the Future of Media & Culture.” Among other things, the paper inventories the many ways in which policymakers in Washington and elsewhere are stepping up regulation of commercial advertising and marketing efforts-and highlights the common themes that unite them. Unfortunately, the report is already over 50 pages long and we keep finding new threats to discuss!

This regulatory tsunami could not come at a worse time, of course, since an attack on advertising is tantamount to an attack on media itself, and media is at a critical point of technological change. As we have pointed out repeatedly, the vast majority of media and content in this country is supported by commercial advertising in one way or another-particularly in the era of “free” content and services.[1]

An Attack on Advertising Will Hurt Consumers

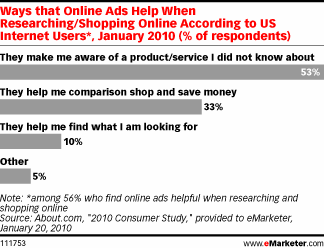

But there’s a more important reason to fear Washington’s new war on advertising: It will hurt consumer welfare. That’s because advertising provides important information and signals to consumers about goods and services that are competing for their attention and business—and that scarcest of all things in the modern world, consumers’ attention. Continue reading →

Last July, Adam Thierer and I argued in a Forbes.com piece that the Microsoft/Yahoo! search partnership should be cause for “celebration among as a good thing for consumers. By providing a strong competitor with a combined 28% market share, the deal should also be a source of relief at Google, which has come under increasing attack for its supposed market dominance.” Today, 205 days later, the companies have finally announced that EU and US antitrust regulators have approved their deal.

So… how does a delay of nearly seven months help consumers? Wouldn’t we be better off if the two companies had been able to start working together immediately to develop a stronger search engine competitor without this “Mother, May I?” routine?

Last year, I described how Microsoft’s delayed entry into search advertising put them at a serious disadvantage in competing with Google. (The company dithered over buying search ad startup Overture and ultimately decided to build its own system—which proved a serious miscalculation.) I’ll just reiterate what we said about the Yahoo!/Microsoft deal when it was first announced.

Yahoo!/Microsoft pact is just the latest pairing of Web 1.0 titans struggling to reinvent themselves and compete with Google, a titan that still thinks of itself as a start-up. All three companies will struggle to meet new challenges as search evolves toward the social(reflecting what your friends like), the semantic (reflecting the precise, rather than presumed, meanings of Web content), the personalized (reflecting your own preferences) and the interactive (including user-generated comments or reviews)…. Continue reading →

Over at “Convergences,” I write on the origins of the idea of a “public option” for health insurance. In part, I note:

At a superficial level, the “public option” for health care is both appealing and puzzling. From a competition policy standpoint, the entry into the market of a subsidized competitor offering a wide array of benefits certainly might put downward pressure on prices as well as easing humanitarian concerns about access. Equally obvious, though, are objections. What mechanism of accountability would exist to ensure that this subsidized entity is well run? It cannot be allowed to go bankrupt; nor is it likely that unhappy customers would have much leeway in suing it. How would it avoid driving private insurers out of the market for low-end service entirely? How much of a subsidy would it get, and how is this to be funded?

Since the party and administration that sponsored this proposal are associated with the intelligentsia, however, people hoping to improve the health care system probably felt entitled to trust that these questions had good answers. Somewhere, someone deep in the bowels of the brain trust had considered these issues. Curious about this, I found myself reading one of the more serious works to address the public option, a paper by Randall D. Cebul, James B. Rebitzer, Lowell J. Taylor and Mark E. Votruba entitled, “Unhealthy Insurance Markets: Search Frictions and the Cost and Quality of Health Insurance,” identified as NBER Working Paper No. 14455, from October 2008.

Read my whole piece, here.

At the FTC’s second Exploring Privacy roundtable at Berkeley in January, many of the complaints about online advertising centered on how difficult it was to control the settings for Adobe’s Flash player, which is used to display ads, videos and a wide variety on other graphic elements on most modern webpages, as well the potential for unscrupulous data collectors to “re-spawn” standard (HTTP) cookies even after a user deleted them simply by referencing the Flash cookie on a user’s computer from that domain—thus circumventing the user’s attempt to clear out their own cookies. Adobe to the first criticism by promising to include better privacy management features in Flash 10.1 and by condemning such re-spawning and calling for “a mix of technology tools and regulatory efforts” to deal with the problem (including FTC enforcement). (Adobe’s filing offers a great history of Flash, a summary of its use and an introduction to Flash Cookies, which Adam Marcus detailed here.)

Earlier this week (and less than three weeks later), Adobe rolled out Flash 10.1, which offers an ingenious solution to the problem of how to manage flash cookies: Flash now simply integrates its privacy controls with Internet Explorer, Firefox and Chrome (and will soon do so with Safari). So when the user turns on “private browsing mode” in these browser, the Flash Cookies will be stored only temporarily, allowing users to use the full functionality of the site, but the Flash Player will “automatically clear any data it might store during a private browsing session, helping to keep your history private.” That’s a pretty big step and an elegantly simple to the problem of how to empower users to take control of their own privacy. Moreover:

Flash Player separates the local storage used in normal browsing from the local storage used during private browsing. So when you enter private browsing mode, sites that you previously visited will not be able to see information they saved on your computer during normal browsing. For example, if you saved your login and password in a web application powered by Flash during normal browsing, the site won’t remember that information when you visit the site under private browsing, keeping your identity private.

Continue reading →

It’s been a busy week in the Googlesphere. Google made headlines earlier this week when it aired a televised ad for the first time in the company’s history, and again yesterday when it unveiled Buzz, its new social networking platform. Today, Google announced bold plans to build an experimental fiber-to-the-home broadband network that’s slated to eventually deliver a whopping gigabit per second of Internet connectivity to 500,000 U.S. homes.

Google’s ambitious broadband announcement comes as welcome news for anybody who pines for greater broadband competition and, more broadly, infrastructure wealth creation in America. To date, Google has dabbled in broadband in the form of metro Wi-Fi, but hasn’t embarked on anything of this scale. Laying fiber to residences is not cheap or easy, as Verizon has learned the hard way, and Google will undoubtedly have to devote some serious resources to this experiment if it is to realize its lofty goals.

It’s important to remember, however, that Google is first and foremost a content company, not an infrastructure company. Google’s generally awesome products, from search to video to email, attract masses of loyal users. In turn, advertisers flock to Google, spending billions in hopes of reaching its gigantic, precisely-targetable audience. This business model enables Google to invest in developing a steady stream of free services, like Google Voice, Google Apps, and Google Maps Navigation.

So it won’t be too surprising if Google’s broadband experiment doesn’t initially generate enough revenue to cover its costs. In fact, I’m skeptical that Google even anticipates its network will ever become a profit center. Rather, chances are Google won’t be at all concerned if its broadband service doesn’t break even as long as it bolsters the Google brand and spurs larger telecom companies to get more aggressive in upgrading their broadband speeds (which, indirectly, benefits Google).

Google’s broadband agenda is great news for consumers, of course. Who can complain if Google is willing to invest in building a fiber-to-the-home broadband network and is willing to charge below-cost prices? Not me!

Continue reading →

By Berin Szoka & Adam Thierer

We learned from The Wall Street Journal yesterday that “Federal Communications Commission Chairman Julius Genachowski gets a little peeved when people suggests that he wants to regulate the Internet.” He told a group of Journal reporters and editors today that: “I don’t see any circumstances where we’d take steps to regulate the Internet itself,” and “I’ve been clear repeatedly that we’re not going to regulate the Internet.”

We learned from The Wall Street Journal yesterday that “Federal Communications Commission Chairman Julius Genachowski gets a little peeved when people suggests that he wants to regulate the Internet.” He told a group of Journal reporters and editors today that: “I don’t see any circumstances where we’d take steps to regulate the Internet itself,” and “I’ve been clear repeatedly that we’re not going to regulate the Internet.”

We’re thankful to hear Chairman Julius Genachowski to make that promise. We’ll certainly hold him to it. But you will pardon us if we remain skeptical (and, in advance, if you hear a constant stream of “I told you so” from us in the months and years to come). If the Chairman is “peeved” at the suggestion that the FCC might be angling to extend its reach to include the Internet and new media platforms and content, perhaps he should start taking a closer look at what his own agency is doing—and think about the precedents he’s setting for future Chairmen who might not share his professed commitment not to regulate the ‘net. Allow us to cite just a few examples:

Net Neutrality Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

We’re certainly aware of the argument that the FCC’s proposed net neutrality regime is not tantamount to Internet regulation—but we just don’t buy it. Not for one minute.

First, Chairman Genachowski seems to believe that “the Internet” is entirely distinct from the physical infrastructure that brings “cyberspace” to our homes, offices and mobile devices. The WSJ notes, “when pressed, [Genachowski] admitted he was referring to regulating Internet content rather than regulating Internet lines.” OK, so let’s just make sure we have this straight: The FCC is going to enshrine in law the principle that “gatekeepers” that control the “bottleneck” of broadband service can only be checked by having the government enforce “neutrality” principles in the same basic model of “common carrier” regulation that once applied to canals, railroads, the telegraph and telephone. But when it comes to accusations of “gatekeeper” power at the content/services/applications “layers” of the Internet, the FCC is just going to step back and let markets sort things out? Sorry, we’re just not buying it. Continue reading →

Third on the headlines today on TechMeme (perhaps the leading tech news aggregator) is this headline: “An Apology To Our Readers,” a heart-felt piece from TechCrunch editor Michael Arrington disclosing that a TechCrunch intern had, on at least two occasions, demanded computers from start-ups as compensation for writing favorable blog posts about them on the highly influential site. The intern was immediately suspended and, when the allegation was confirmed, terminated. Arrington made no excuses for Daniel Brusilovsky on account of his age (he’s under 18). You can read Daniel’s response here.

If this incident demonstrates anything, it’s just how essential it is for a site like TechCrunch to, as Arrington promised his readers in closing, “maintain complete transparency with you on how we operate, even when it isn’t such an easy thing to do.” Arrington went so far as to have “deleted all content created by this person on our blogs”—indeed, “every word written by this person on the TechCrunch network,” which presumably includes comments.

One might take from this the lesson that the press, as it evolves from the newspaper model towards something blog-ier but still hard to pin down precisely, can police itself pretty darn well. Alas, the FTC has taken a much dimmer view of the ability of reputational incentives to discipline the influence that might be exerted by “blogola” payments (cash or in-kind) on editorial discretion and journalistic creation. Continue reading →

Advertising is increasingly under attack in Washington. In fact, we’re busy finishing up a paper with the working title: “The New Assault on Advertising: What it Means for the Future of Media & Culture.” Among other things, the paper inventories the many ways in which policymakers in Washington and elsewhere are stepping up regulation of commercial advertising and marketing efforts-and highlights the common themes that unite them. Unfortunately, the report is already over 50 pages long and we keep finding new threats to discuss!

Advertising is increasingly under attack in Washington. In fact, we’re busy finishing up a paper with the working title: “The New Assault on Advertising: What it Means for the Future of Media & Culture.” Among other things, the paper inventories the many ways in which policymakers in Washington and elsewhere are stepping up regulation of commercial advertising and marketing efforts-and highlights the common themes that unite them. Unfortunately, the report is already over 50 pages long and we keep finding new threats to discuss!

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.