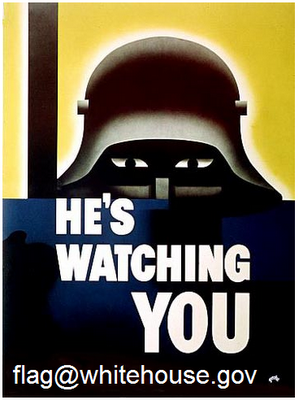

Today a broad array of civil liberties groups, think tanks, and technology companies launched the Digital Due Process coalition. The coalition’s mission is to educate lawmakers and the public about the need to update U.S. privacy laws to better safeguard individual information online and ensure that federal privacy statutes accurately reflect the realities of the digital age.

Over 20 organizations belong to the Digital Due Process coalition, including such odd bedfellows as AT&T, Google, Microsoft, the Center for Democracy & Technology, the American Civil Liberties Union, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, The Progress & Freedom Foundation (where Berin works), the Competitive Enterprise Institute (where Ryan works), the Internet Technology & Innovation Foundation, Citizens Against Government Waste, and Americans for Tax Reform. The full member list is available at the coalition’s website.

Amidst the heated tech policy wars, it’s not every day that such a diverse group of organizations comes together to endorse a unified set of core principles for legislative reform. Over two years in the making, the Digital Due Process coalition, spearheaded by the Center for Democracy & Technology, is a testament to the broad consensus that’s emerged among business leaders, activists, and scholars regarding the inadequacies of the current legal regime intended to protect Americans’ privacy from government snooping and the need for Congress to revisit decades-old privacy statutes. It also represents a revival of a bipartisan consensus on the need for reform reached back in 2000, when the Republican-led House Judiciary Committee voted 20-1 to approve very similar reforms (HR 5018).

Today, in the digital age, robust privacy laws are more important than ever. That’s because U.S. courts have been unwilling to extend the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable search and seizure to individual information stored with third parties such as cloud computing providers. Thus, while government authorities must get a search warrant based on probable cause before they can lawfully rifle through documents stored in your desk, basement, or safe deposit box, information you store on the cloud enjoys no Constitutional protection. (Some legal scholars argue this interpretation of the Fourth Amendment, referred to as the Third Party Doctrine, is outdated and deficient. See, for example, Jim Harper’s excellent 2008 article in the American University Law Review.)

providers next month if Federal Communications Commission Chairman Julius Genachowski gets his way. In a milestone speech on Monday, Genachowski proposed sweeping new regulations that would give the FCC the formal authority to dictate application and network management practices to companies that offer Internet access, including wireless carriers like AT&T and Verizon Wireless.

providers next month if Federal Communications Commission Chairman Julius Genachowski gets his way. In a milestone speech on Monday, Genachowski proposed sweeping new regulations that would give the FCC the formal authority to dictate application and network management practices to companies that offer Internet access, including wireless carriers like AT&T and Verizon Wireless. Electronic Frontier Foundation and the American Civil Liberties Union. They

Electronic Frontier Foundation and the American Civil Liberties Union. They

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.