Articles by Adam Thierer

Senior Fellow in Technology & Innovation at the R Street Institute in Washington, DC. Formerly a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, President of the Progress & Freedom Foundation, Director of Telecommunications Studies at the Cato Institute, and a Fellow in Economic Policy at the Heritage Foundation.

Senior Fellow in Technology & Innovation at the R Street Institute in Washington, DC. Formerly a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, President of the Progress & Freedom Foundation, Director of Telecommunications Studies at the Cato Institute, and a Fellow in Economic Policy at the Heritage Foundation.

Venture capitalist Bill Gurley asked a good question in a Tweet late last night when he was “wondering if Apple’s 30% rake isn’t a foolish act of hubris. Why drive Amazon, Facebook, and others to different platforms?” As most of you know, Gurley is referring to Apple’s announcement in February that it would require a 30% cut of app developers’ revenues if they wanted a place in the Apple App Store.

Indeed, why would Apple be so foolish? Of course, some critics will cry “monopoly!” and claim that Apple’s “act of hubris” was simply a logical move by a platform monopolist to exploit its supposedly dominant position in the mobile OS / app store marketplace. But what then are we to make of Amazon’s big announcement yesterday that it was jumping in the ring with its new app store for Android? And what are we to make of the fact that Google immediately responded to Apple’s 30% announcement by offering publishers a more reasonable 10%-of-the-cut deal? And, as Gurley notes, you can’t forget about Facebook. Who knows what they have up their sleeve next. They’ve denied any interest in marketing their own phone and, at least so far, have not announced any intention to offer a competing app store, but why would they need to? Their platform can integrate apps directly into it! Oh, and don’t forget that there’s a little company called Microsoft out there still trying to stake its claim to a patch of land in the mobile OS landscape. Oh, and have you visited the HP-Palm development center lately? Some very interesting things going on there that we shouldn’t ignore.

Indeed, why would Apple be so foolish? Of course, some critics will cry “monopoly!” and claim that Apple’s “act of hubris” was simply a logical move by a platform monopolist to exploit its supposedly dominant position in the mobile OS / app store marketplace. But what then are we to make of Amazon’s big announcement yesterday that it was jumping in the ring with its new app store for Android? And what are we to make of the fact that Google immediately responded to Apple’s 30% announcement by offering publishers a more reasonable 10%-of-the-cut deal? And, as Gurley notes, you can’t forget about Facebook. Who knows what they have up their sleeve next. They’ve denied any interest in marketing their own phone and, at least so far, have not announced any intention to offer a competing app store, but why would they need to? Their platform can integrate apps directly into it! Oh, and don’t forget that there’s a little company called Microsoft out there still trying to stake its claim to a patch of land in the mobile OS landscape. Oh, and have you visited the HP-Palm development center lately? Some very interesting things going on there that we shouldn’t ignore.

What these developments illustrate is a point that I have constantly reiterated here: Continue reading →

Jane Yakowitz of Brooklyn Law School recently posted an interesting 63-page paper on SSRN entitled, “Tragedy of the Data Commons.” For those following the current privacy debates, it is must reading since it points out a simple truism: increased data privacy regulation could result in the diminution of many beneficial information flows.

Jane Yakowitz of Brooklyn Law School recently posted an interesting 63-page paper on SSRN entitled, “Tragedy of the Data Commons.” For those following the current privacy debates, it is must reading since it points out a simple truism: increased data privacy regulation could result in the diminution of many beneficial information flows.

Cutting against the grain of modern privacy scholarship, Yakowitz argues that “The stakes for data privacy have reached a new high water mark, but the consequences are not what they seem. We are at great risk not of privacy threats, but of information obstruction.” (p. 58) Her concern is that “if taken to the extreme, data privacy can also make discourse anemic and shallow by removing from it relevant and readily attainable facts.” (p. 63) In particular, she worries that “The bulk of privacy scholarship has had the deleterious effect of exacerbating public distrust in research data.”

Yakowitz is right to be concerned. Access to data and broad data sets that include anonymized profiles of individuals is profound importantly for countless sectors and professions: journalism, medicine, economics, law, criminology, political science, environmental sciences, and many, many others. Yakowitz does a brilliant job documenting the many “fruits of the data commons” by showing how “the benefits flowing from the data commons are indirect but bountiful.” (p. 5) This isn’t about those sectors making money. It’s more about how researchers in those fields use information to improve the world around us. In essence, more data = more knowledge. If we want to study and better understand the world around us, researchers need access to broad (and continuously refreshed) data sets. Overly restrictive privacy regulations or forms of liability could slow that flow, diminish or weaken research capabilities and output, and leave society less well off because of the resulting ignorance we face. Continue reading →

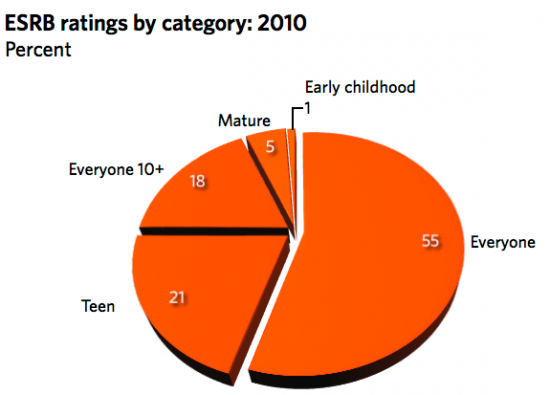

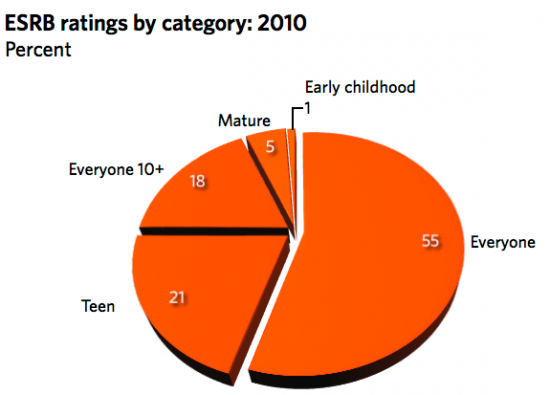

Five years ago this month, I penned a white paper on “Fact and Fiction in the Debate over Video Game Regulation” that I have been meaning to update ever since but just never seem to get around to it. One of the myths I aimed to debunk in the paper was the belief that most video games contain intense depictions of violence or sexuality. This argument drives many of the crusades to regulate video games. In my old study, I aggregated several years worth of data about video game ratings and showed that the exact opposite was the case: the majority of games sold each year were rating “E” for everyone or “E10+” (Everyone 10 and over) by the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB).

Five years ago this month, I penned a white paper on “Fact and Fiction in the Debate over Video Game Regulation” that I have been meaning to update ever since but just never seem to get around to it. One of the myths I aimed to debunk in the paper was the belief that most video games contain intense depictions of violence or sexuality. This argument drives many of the crusades to regulate video games. In my old study, I aggregated several years worth of data about video game ratings and showed that the exact opposite was the case: the majority of games sold each year were rating “E” for everyone or “E10+” (Everyone 10 and over) by the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB).

Thanks to this new article by Ars Technica‘s Ben Kuchera, we know that this trend continues. Kuchera reports that out of 1,638 games rated by the ESRB in 2010, only 5% were rated “M” for Mature. As a percentage of top sellers, the percentage of “M”-rated games is a bit higher, coming in at 29%. But that’s hardly surprising since there are always a few big “M”-rated titles that are the power-sellers among young adults each year. Still, most of the best sellers don’t contain extreme violence or sexuality.

Continue reading →

Here are some quick thoughts on the proposed AT&T – T-Mobile merger, mostly borrowed from my previous writing on the wireless marketplace. First, however, I highly recommend this excellent analysis of the issue by Larry Downes, which cuts through the hysteria we’re already hearing and offers a sober look at the issues at stake here. Anyway, here are a few of my random thoughts on the deal:

* The deal will likely be approved: First, to cut to the chase.. After much wrangling, the deal will probably be approved primarily because of two factors, both of which help political officials as much as AT&T: (1) The deal delivers upon the National Broadband Plan promise of getting the country blanketed with wireless broadband; and (2) it “brings home” T-Mobile by giving an American company control of a German-held interest. As Larry Dignan of ZNet says, it is tantamount to “playing the patriotism card.”

* One reason it might not be approved: Some Administration critics, especially from the more liberal part of the Democratic base, could make this a litmus test for Obama administration’s antitrust enforcement efforts. In the wake of the Comcast merger approval — albeit after several pounds of flesh were handed over “voluntarily” to get the deal approved — some of the Administration’s base will be looking for blood. I remember how the Powell FCC was under real heat to “get tough” on mergers back in 2001-02 and during that time blocked the proposed DirecTV-EchoStar deal, possibly as a result of the pressure. The same thing could happen to AT&T – T-Mobile here.

* It’s all about spectrum: From AT&T’s perspective, this deal is all about getting more high-quality spectrum, which is in increasingly short supply. Indeed, as Jerry Brito noted earlier, this merger should serve as another wake-up call regarding the need to get spectrum reform going again to ensure that existing players can reallocate their spectrum to those who demand it most. (Hint: Incentivize the TV broadcasters to sell... NOW!) But, in the short-term, this deal helps AT&T built out a more robust nationwide wireless network. Over the long-haul, that should help T-Mobile deliver better service to its customers. Continue reading →

My thanks to Linton Weeks of NPR who reached out to me for comment for a story he was doing on the impact of the Internet and digital technology on culture and our attention spans. His essay, “We Are Just Not Digging The Whole Anymore,” is an interesting exploration of the issue, although it is clear that Weeks, like Nick Carr (among others), is concerned about what the Net is doing to our brains. He says:

We just don’t do whole things anymore. We don’t read complete books — just excerpts. We don’t listen to whole CDs — just samplings. We don’t sit through whole baseball games — just a few innings. Don’t even write whole sentences. Or read whole stories like this one. We care more about the parts and less about the entire. We are into snippets and smidgens and clips and tweets. We are not only a fragmented society, but a fragment society. And the result: What we gain is the knowledge — or the illusion of knowledge — of many new, different and variegated aspects of life. What we lose is still being understood.

After reading the entire piece I realized that some of my comments to Weeks probably came off as a bit more pessimistic about things than I actually am. I told him, for example, that “Long-form reading, listening and viewing habits are giving way to browse-and-choose consumption,” and that “With the increase in the number of media options — or distractions, depending on how you look at them — something has to give, and that something is our attention span.”

Luckily, however, Weeks was kind enough to also give me the last word in the story in which I pointed out that it would be a serious mistake to conclude “that we’re all growing stupid, or losing our ability to think, or losing our appreciation of books, albums or other types of long-form content.” Instead, I argued: Continue reading →

On numerous occasions here and elsewhere I have cited the enormous influence that Virginia Postrel’s 1998 book, The Future and Its Enemies, has had on me. Her “dynamist” versus “stasis” paradigm helps us frame and better understand almost all debates about technological progress. I cannot recommend that book highly enough.

On numerous occasions here and elsewhere I have cited the enormous influence that Virginia Postrel’s 1998 book, The Future and Its Enemies, has had on me. Her “dynamist” versus “stasis” paradigm helps us frame and better understand almost all debates about technological progress. I cannot recommend that book highly enough.

In her latest Wall Street Journal column, Postrel considers what makes the iPad such a “magical” device and in doing so, she takes on the logical set forth in Jonathan Zittrain 2009 book, The Future of the Internet and How to Stop It, although she doesn’t cite the book by name in her column. You will recall that in that book and his subsequent essays, Prof. Zittrain made Steve Jobs and his iPhone out to be the great enemy of digital innovation — at least as Zittrain defined it. How did Zittrain reach this astonishing conclusion and manage to turn Jobs into a pariah and his devices into the supposed enemy of innovation? It came down to “generativity,” Zittrain said, by which he meant technologies or networks that invite or allow tinkering and all sorts of creative uses. Zittrain worships general-purpose personal computers and the traditional “best efforts” Internet. By contrast, he decried “sterile, tethered” digital “appliances” like the iPhone, which he claimed limited generativity and innovation, mostly because of their generally closed architecture.

In her column, Postrel agrees that the iPad is every bit as closed as Zittrain feared iPhone successor devices would be. She notes: “customers haven’t the foggiest idea how the machine works. The iPad is completely opaque. It is a sealed box. You can’t see the circuitry or read the software code. You can’t even change the battery.” But Postrel continues on to explain why the hand-wringing about perfect openness is generally overblown and, indeed, more than a bit elitist: Continue reading →

Twitter could be in for a world of potential pain. Regulatory pain, that is. The company’s announcement on Friday that it would soon be cracking down on the uses of its API by third parties is raising eyebrows in cyberspace and, if recent regulatory history is any indicator, this high-tech innovator could soon face some heat from regulatory advocates and public policy makers. If this thing goes down as I describe it below, it will be one hell of a fight that once again features warring conceptions of “Internet freedom” butting heads over the question of whether Twitter should be forced to share its API with rivals via some sort of “open access” regulatory regime or “API neutrality,” in particular. I’ll explore that possibility in this essay. First, a bit of background.

Twitter could be in for a world of potential pain. Regulatory pain, that is. The company’s announcement on Friday that it would soon be cracking down on the uses of its API by third parties is raising eyebrows in cyberspace and, if recent regulatory history is any indicator, this high-tech innovator could soon face some heat from regulatory advocates and public policy makers. If this thing goes down as I describe it below, it will be one hell of a fight that once again features warring conceptions of “Internet freedom” butting heads over the question of whether Twitter should be forced to share its API with rivals via some sort of “open access” regulatory regime or “API neutrality,” in particular. I’ll explore that possibility in this essay. First, a bit of background.

Understanding Forced Access Regulation

In the field of communications law, the dominant public policy fight of the past 15 years has been the battle over “open access” and “neutrality” regulation. Generally speaking, open access regulations demand that a company share its property (networks, systems, devices, or code) with rivals on terms established by law. Neutrality regulation is a variant of open access regulation, which also requires that systems be used in ways specified by law, but usually without the physical sharing requirements. Both forms of regulation derive from traditional common carriage principles / regulatory regimes. Critics of such regulation, which would most definitely include me, decry the inefficiencies associated with such “forced access” regimes, as we prefer to label them. Forced access regulation also raises certain constitutional issues related to First and Fifth Amendment rights of speech and property. Continue reading →

Yet another hearing on privacy issues has been slated for this coming Wednesday, March 16th. This latest one is in the Senate Commerce Committee and it is entitled “The State of Online Consumer Privacy.” As I’m often asked by various House and Senate committee staffers to help think of good questions for witnesses, I’m listing a few here that I would love to hear answered by any Federal Trade Commission (FTC) or Dept. of Commerce (DoC) officials testifying. You will recall that both agencies released new privacy “frameworks” late last year and seem determined to move America toward a more “European-ized” conception of privacy regulation. [See our recent posts critiquing the reports here.] Here are a few questions that should be put to the FTC and DoC officials, or those who support the direction they are taking us. Please feel free to suggest others:

- Before implying that we are experiencing market failure, why hasn’t either the FTC or DoC conducted a thorough review of online privacy policies to evaluate how well organizational actions match up with promises made in those policies?

- To the extent any sort of internal cost-benefit analysis was done internally before the release of these reports, has an effort been made to quantify the potential size of the hidden “privacy tax” that new regulations like “Do Not Track” could impose on the market?

- Has the impact of new regulations on small competitors or new entrants in the field been considered? Has any attempt been made to quantify how much less entry / innovation would occur as a result of such regulation?

- Were any economists from the FTC’s Economics Bureau consulted before the new framework was released? Did the DoC consult any economists?

- Why do FTC and DoC officials believe that citing unscientific public opinions polls from regulatory advocacy organizations serves as a surrogate for serious cost-benefit analysis or an investigation into how well privacy policies actual work in the marketplace?

- If they refuse to conduct more comprehensive internal research, have the agencies considered contracting with external economists to build a body of research looking into these issues (as the Federal Communications Commission did in a decade ago in its media ownership proceeding)?

- Has either agency attempted to determine consumer’s “willingness to pay” for increased privacy regulation?

- More generally, where is the “harm” and aren’t there plenty of voluntary privacy-enhancing tools out there that privacy-sensitive users can tap to shield their digital footsteps, if they feel so inclined?

In one sense, Siva Vaidhyanathan’s new book, The Googlization of Everything (And Why Should Worry), is exactly what you would expect: an anti-Google screed that predicts a veritable techno-apocalypse will befall us unless we do something to deal with this company that supposedly “rules like Caesar.” (p. xi) Employing the requisite amount of panic-inducing Chicken Little rhetoric apparently required to sell books these days, Vaidhyanathan tells us that “the stakes could not be higher,” (p. 7) because the “corporate lockdown of culture and technology” (p. xii) is imminent.

In one sense, Siva Vaidhyanathan’s new book, The Googlization of Everything (And Why Should Worry), is exactly what you would expect: an anti-Google screed that predicts a veritable techno-apocalypse will befall us unless we do something to deal with this company that supposedly “rules like Caesar.” (p. xi) Employing the requisite amount of panic-inducing Chicken Little rhetoric apparently required to sell books these days, Vaidhyanathan tells us that “the stakes could not be higher,” (p. 7) because the “corporate lockdown of culture and technology” (p. xii) is imminent.

After lambasting the company in a breathless fury over the opening 15 pages of the book, Vaidhyanathan assures us that “nothing about this means that Google’s rule is as brutal and dictatorial as Caesar’s. Nor does it mean that we should plot an assassination,” he says. Well, that’s a relief! Yet, he continues on to argue that Google is sufficiently dangerous that “we should influence—even regulate—search systems actively and intentionally, and thus take responsibility for how the Web delivers knowledge.” (p. xii) Why should we do that? Basically, Google is just too damn good at what it does. The company has the audacity to give consumers exactly what they want! “Faith in Google is dangerous because it increases our appetite for goods, services, information, amusement, distraction, and efficiency.” (p. 55) That is problematic, Vaidhyanathan says, because “providing immediate gratification draped in a cloak of corporate benevolence is bad faith.” (p. 55) But this begs the question: What limiting principle should be put in place to curb our appetites, and who or what should enforce it? Continue reading →

We’ve said it here before too may times to count: When it comes to the future of content and services — especially online or digitally-delivered content and services — there is no free lunch. Something has to pay for all that stuff and increasingly that something is advertising. But not just any type of advertising — targeted advertising is the future. We see that again today with Skype’s announcement that it is rolling out an advertising scheme as well as in this Wall Street Journal story (“TV’s Next Wave: Tuning In to You“) about how cable and satellite TV providers are ramping up their targeted advertising efforts.

No doubt, we’ll soon hear the same old complaints and fears trotted out about these developments. We’ll hear about how “annoying” such ads are or how “creepy” they are. Yet, few will bother detailing what the actual harm is in being delivered more tailored or targeted commercial messages. After all, there’s actually a benefit to receiving ads that may be of more interest to us. Much traditional advertising was quite “spammy” in that it was sent to the mass market without a care in the world about who might see or hear it. But in a diverse society, it would be optimal if the ads you saw better reflected your actual interests / tastes. And that’s a primary motivation for why so many content and service providers are turning to ad targeting techniques. As Skype noted in its announcement today: “We may use non-personally identifiable demographic data (e.g. location, gender and age) to target ads, which helps ensure that you see relevant ads. For example, if you’re in the US, we don’t want to show you ads for a product that is only available in the UK.” Similarly, the Journal article highlights a variety of approaches that television providers are using to better tailor ads to their viewers.

Some will still claim it’s too “creepy.” But, as I noted in my recent filing to the Federal Trade Commission on its new privacy green paper: Continue reading →

Indeed, why would Apple be so foolish? Of course, some critics will cry “monopoly!” and claim that Apple’s “act of hubris” was simply a logical move by a platform monopolist to exploit its supposedly dominant position in the mobile OS / app store marketplace. But what then are we to make of Amazon’s big announcement yesterday that it was jumping in the ring with its new app store for Android? And what are we to make of the fact that Google immediately responded to Apple’s 30% announcement by offering publishers a more reasonable 10%-of-the-cut deal? And, as Gurley notes, you can’t forget about Facebook. Who knows what they have up their sleeve next. They’ve denied any interest in marketing their own phone and, at least so far, have not announced any intention to offer a competing app store, but why would they need to? Their platform can integrate apps directly into it! Oh, and don’t forget that there’s a little company called Microsoft out there still trying to stake its claim to a patch of land in the mobile OS landscape. Oh, and have you visited the HP-Palm development center lately? Some very interesting things going on there that we shouldn’t ignore.

Indeed, why would Apple be so foolish? Of course, some critics will cry “monopoly!” and claim that Apple’s “act of hubris” was simply a logical move by a platform monopolist to exploit its supposedly dominant position in the mobile OS / app store marketplace. But what then are we to make of Amazon’s big announcement yesterday that it was jumping in the ring with its new app store for Android? And what are we to make of the fact that Google immediately responded to Apple’s 30% announcement by offering publishers a more reasonable 10%-of-the-cut deal? And, as Gurley notes, you can’t forget about Facebook. Who knows what they have up their sleeve next. They’ve denied any interest in marketing their own phone and, at least so far, have not announced any intention to offer a competing app store, but why would they need to? Their platform can integrate apps directly into it! Oh, and don’t forget that there’s a little company called Microsoft out there still trying to stake its claim to a patch of land in the mobile OS landscape. Oh, and have you visited the HP-Palm development center lately? Some very interesting things going on there that we shouldn’t ignore.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.