Articles by Adam Thierer

Senior Fellow in Technology & Innovation at the R Street Institute in Washington, DC. Formerly a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, President of the Progress & Freedom Foundation, Director of Telecommunications Studies at the Cato Institute, and a Fellow in Economic Policy at the Heritage Foundation.

Senior Fellow in Technology & Innovation at the R Street Institute in Washington, DC. Formerly a senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, President of the Progress & Freedom Foundation, Director of Telecommunications Studies at the Cato Institute, and a Fellow in Economic Policy at the Heritage Foundation.

Last month, it was my great pleasure to serve as a “provocateur” at the IAPP’s (Int’l Assoc. of Privacy Professionals) annual “Navigate” conference. The event brought together a diverse audience and set of speakers from across the globe to discuss how to deal with the various privacy concerns associated with current and emerging technologies.

My remarks focused on a theme I have developed here for years: There are no simple, silver-bullet solutions to complex problems such as online safety, security, and privacy. Instead, only a “layered” approach incorporating many different solutions–education, media literacy, digital citizenship, evolving society norms, self-regulation, and targeted enforcement of existing legal standards–can really help us solve these problems. Even then, new challenges will present themselves as technology continues to evolve and evade traditional controls, solutions, or norms. It’s a never-ending game, and that’s why education must be our first-order solution. It better prepares us for an uncertain future. (I explained this approach in far more detail in this law review article.)

Anyway, if you’re interested in an 11-minute video of me saying all that, here ya go. Also, down below I have listed several of the recent essays, papers, and law review articles I have done on this issue.

Continue reading →

Ronald J. Deibert is the director of The Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and the author of an important new book, Black Code: Inside the Battle for Cyberspace, an in-depth look at the growing insecurity of the Internet. Specifically, Deibert’s book is a meticulous examination of the “malicious threats that are growing from the inside out” and which “threaten to destroy the fragile ecosystem we have come to take for granted.” (p. 14) It is also a remarkably timely book in light of the recent revelations about NSA surveillance and how it is being facilitated with the assistance of various tech and telecom giants.

Ronald J. Deibert is the director of The Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and the author of an important new book, Black Code: Inside the Battle for Cyberspace, an in-depth look at the growing insecurity of the Internet. Specifically, Deibert’s book is a meticulous examination of the “malicious threats that are growing from the inside out” and which “threaten to destroy the fragile ecosystem we have come to take for granted.” (p. 14) It is also a remarkably timely book in light of the recent revelations about NSA surveillance and how it is being facilitated with the assistance of various tech and telecom giants.

The clear and colloquial tone that Deibert employs in the text helps make arcane Internet security issues interesting and accessible. Indeed, some chapters of the book almost feel like they were pulled from the pages of techno-thriller, complete with villainous characters, unexpected plot twists, and shocking conclusions. “Cyber crime has become one of the world’s largest growth businesses,” Deibert notes (p. 144) and his chapters focus on many prominent recent examples, including cyber-crime syndicates like Koobface, government cyber-spying schemes like GhostNet, state-sanctioned sabotage like Stuxnet, and the vexing issue of zero-day exploit sales.

Deibert is uniquely qualified to narrate this tale not just because he is a gifted story-teller but also because he has had a front row seat in the unfolding play that we might refer to as “How Cyberspace Grew Less Secure.” Continue reading →

I was honored to be asked by the editors at Reason magazine to be a part of their “Revolutionary Reading” roundup of “The 9 Most Transformative Books of the Last 45 Years.” Reason is celebrating its 45th anniversary and running a wide variety of essays looking back at how liberty has fared over the past half-century. The magazine notes that “Statism has hardly gone away, but the movement to roll it back is stronger than ever.” For this particular feature, Reason’s editors “asked seven libertarians to recommend some of the books in different fields that made [the anti-statist] cultural and intellectual revolution possible.”

I was honored to be asked by the editors at Reason magazine to be a part of their “Revolutionary Reading” roundup of “The 9 Most Transformative Books of the Last 45 Years.” Reason is celebrating its 45th anniversary and running a wide variety of essays looking back at how liberty has fared over the past half-century. The magazine notes that “Statism has hardly gone away, but the movement to roll it back is stronger than ever.” For this particular feature, Reason’s editors “asked seven libertarians to recommend some of the books in different fields that made [the anti-statist] cultural and intellectual revolution possible.”

When Jesse Walker of Reason first contacted me about contributing my thoughts about which technology policy books made the biggest difference, I told him I knew exactly what my choices would be: Ithiel de Sola Pool’s Technologies of Freedom (1983) and Virginia Postrel’s The Future and Its Enemies (1998). Faithful readers of this blog know all too well how much I love these two books and how I am constantly reminding people of their intellectual importance all these years later. (See, for example, this and this.) All my thinking and writing about tech policy over the past two decades has been shaped by the bold vision and recommendations set forth by Pool and Postrel in these beautiful books.

As I note in my Reason write-up of the books: Continue reading →

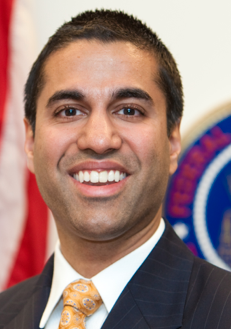

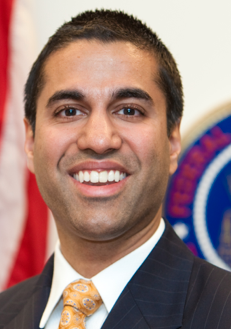

Ajit Pai, a Republican commissioner at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), had an outstanding op-ed in the L.A. Times yesterday about state and local efforts to regulate private taxi or ride-sharing services such as Uber, Lyft, and Sidecar. “Ever since Uber came to California,” Pai notes, “regulators have seemed determined to send Uber and companies like it on a one-way ride out of the Golden State.” Regulators have thrown numerous impediments in their way in California as well as in other states and localities (including here in Washington, D.C.). Pai continues on to discuss how, sadly, “tech start-ups in other industries face similar burdens”:

Ajit Pai, a Republican commissioner at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), had an outstanding op-ed in the L.A. Times yesterday about state and local efforts to regulate private taxi or ride-sharing services such as Uber, Lyft, and Sidecar. “Ever since Uber came to California,” Pai notes, “regulators have seemed determined to send Uber and companies like it on a one-way ride out of the Golden State.” Regulators have thrown numerous impediments in their way in California as well as in other states and localities (including here in Washington, D.C.). Pai continues on to discuss how, sadly, “tech start-ups in other industries face similar burdens”:

For example, Square has created a credit card reader for mobile devices. Small businesses love Square because it reduces costs and is convenient for customers. But some states want a piece of the action. Illinois, for example, has ordered Square to stop doing business in the Land of Lincoln until it gets a money transmitter license, even though the money flows through existing payment networks when Square processes credit cards. If Square had to get licenses in the 47 states with such laws, it could cost nearly half a million dollars, an extraordinary expense for a fledgling company.

He also notes that “Obstacles to entrepreneurship aren’t limited to the tech world”:

Across the country, restaurant associations have tried to kick food trucks off the streets. Auto dealers have used franchise laws to prevent car company Tesla from cutting out the middleman and selling directly to customers. Professional boards, too, often fiercely defend the status quo, impeding telemedicine by requiring state-by-state licensing or in-person consultations and even restricting who can sell tooth-whitening services.

What’s going on here? It’s an old and lamentable tale of incumbent protectionism and outright cronyism, Pai notes: Continue reading →

This afternoon, Berin Szoka asked me to participate in a TechFreedom conference on “COPPA: Past, Present & Future of Children’s Privacy & Media.” [CSPAN video is here.] It was a in-depth, 3-hour, 2-panel discussion of the Federal Trade Commission’s recent revisions to the rules issued under the 1998 Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA).

While most of the other panelists were focused on the devilish details about how COPPA works in practice (or at least should work in practice), I decided to ask a more provocative question to really shake up the discussion: What are we going to do when COPPA fails?

My notes for the event follow down below. I didn’t have time to put them into a smooth narrative, so please pardon the bullet points. Continue reading →

The Mercatus Center at George Mason University has just released a new paper by Brent Skorup and me entitled, “A History of Cronyism and Capture in the Information Technology Sector.” In this 73-page working paper, which we hope to place in a law review or political science journal shortly, we document the evolution of government-granted privileges, or “cronyism,” in the information and communications technology marketplace and in the media-producing sectors. Specifically, we offer detailed histories of rent-seeking and regulatory capture in: the early history of the telephony and spectrum licensing in the United States; local cable TV franchising; the universal service system; the digital TV transition in the 1990s; and modern video marketplace regulation (i.e., must-carry and retransmission consent rules, among others.

The Mercatus Center at George Mason University has just released a new paper by Brent Skorup and me entitled, “A History of Cronyism and Capture in the Information Technology Sector.” In this 73-page working paper, which we hope to place in a law review or political science journal shortly, we document the evolution of government-granted privileges, or “cronyism,” in the information and communications technology marketplace and in the media-producing sectors. Specifically, we offer detailed histories of rent-seeking and regulatory capture in: the early history of the telephony and spectrum licensing in the United States; local cable TV franchising; the universal service system; the digital TV transition in the 1990s; and modern video marketplace regulation (i.e., must-carry and retransmission consent rules, among others.

Our paper also shows how cronyism is slowly creeping into new high-technology sectors.We document how Internet companies and other high-tech giants are among the fastest-growing lobbying shops in Washington these days. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, lobbying spending by information technology sectors has almost doubled since the turn of the century, from roughly $200 million in 2000 to $390 million in 2012. The computing and Internet sector has been responsible for most of that growth in recent years. Worse yet, we document how many of these high-tech firms are increasingly seeking and receiving government favors, mostly in the form of targeted tax breaks or incentives. Continue reading →

Washington Post columnist Robert J. Samuelson published an astonishing essay today entitled, “Beware the Internet and the Danger of Cyberattacks.” In the print edition of today’s Post, the essay actually carries a different title: “Is the Internet Worth It?” Samuelson’s answer is clear: It isn’t. He begins his breathless attack on the Internet by proclaiming:

If I could, I would repeal the Internet. It is the technological marvel of the age, but it is not — as most people imagine — a symbol of progress. Just the opposite. We would be better off without it. I grant its astonishing capabilities: the instant access to vast amounts of information, the pleasures of YouTube and iTunes, the convenience of GPS and much more. But the Internet’s benefits are relatively modest compared with previous transformative technologies, and it brings with it a terrifying danger: cyberwar.

And then, after walking through a couple of worst-case hypothetical scenarios, he concludes the piece by saying:

the Internet’s social impact is shallow. Imagine life without it. Would the loss of e-mail, Facebook or Wikipedia inflict fundamental change? Now imagine life without some earlier breakthroughs: electricity, cars, antibiotics. Life would be radically different. The Internet’s virtues are overstated, its vices understated. It’s a mixed blessing — and the mix may be moving against us.

What I found most troubling about this is that Samuelson has serious intellectual chops and usually sweats the details in his analysis of other issues. He understands economic and social trade-offs and usually does a nice job weighing the facts on the ground instead of engaging in the sort of shallow navel-gazing and anecdotal reasoning that many other weekly newspaper columnist engage in on a regular basis.

But that’s not what he does here. His essay comes across as a poorly researched, angry-old-man-shouting-at-the-sky sort of rant. There’s no serious cost-benefit analysis at work here; just the banal assertion that a new technology has created new vulnerabilities. Really, that’s the extent of the logic at work here. Samuelson could have just as well substituted the automobile, airplanes, or any other modern technology for the Internet and drawn the same conclusion: It opens the door to new vulnerabilities (especially national security vulnerabilities) and, therefore, we would be better off without it in our lives. Continue reading →

Ian Brown and Christopher T. Marsden’s new book, Regulating Code: Good Governance and Better Regulation in the Information Age, will go down as one of the most important Internet policy books of 2013 for two reasons. First, their book offers an excellent overview of how Internet regulation has unfolded on five different fronts: privacy and data protection; copyright; content censorship; social networks and user-generated content issues; and net neutrality regulation. They craft detailed case studies that incorporate important insights about how countries across the globe are dealing with these issues. Second, the authors endorse a specific normative approach to Net governance that they argue is taking hold across these policy arenas. They call their preferred policy paradigm “prosumer law” and it envisions an active role for governments, which they think should pursue “smarter regulation” of code.

Ian Brown and Christopher T. Marsden’s new book, Regulating Code: Good Governance and Better Regulation in the Information Age, will go down as one of the most important Internet policy books of 2013 for two reasons. First, their book offers an excellent overview of how Internet regulation has unfolded on five different fronts: privacy and data protection; copyright; content censorship; social networks and user-generated content issues; and net neutrality regulation. They craft detailed case studies that incorporate important insights about how countries across the globe are dealing with these issues. Second, the authors endorse a specific normative approach to Net governance that they argue is taking hold across these policy arenas. They call their preferred policy paradigm “prosumer law” and it envisions an active role for governments, which they think should pursue “smarter regulation” of code.

In terms of organization, Brown and Marsden’s book follows the same format found in Milton Mueller’s important 2010 book Networks and States: The Global Politics of Internet Governance; both books feature meaty case studies in the middle bookended by chapters that endorse a specific approach to Internet policymaking. (Incidentally, both books were published by MIT Press.) And, also like Mueller’s book, Brown and Marsden’s Regulating Code does a somewhat better job using case studies to explore the forces shaping Internet policy across the globe than it does making the normative case for their preferred approach to these issues. Continue reading →

The Internet’s greatest blessing — its general openness to all speech and speakers — is also sometimes its biggest curse. That is, you cannot expect to have the most widely accessible, unrestricted communications platform the world has ever known and not also have some imbeciles who use it to spew insulting, vile, and hateful comments.

The Internet’s greatest blessing — its general openness to all speech and speakers — is also sometimes its biggest curse. That is, you cannot expect to have the most widely accessible, unrestricted communications platform the world has ever known and not also have some imbeciles who use it to spew insulting, vile, and hateful comments.

It is important to put things in perspective, however. Hate speech is not the norm online. The louts who spew hatred represent a small minority of all online speakers. The vast majority of online speech is of a socially acceptable — even beneficial — nature.

Still, the problem of hate speech remains very real and a diverse array of strategies are needed to deal with it. The sensible path forward in this regard is charted by Abraham H. Foxman and Christopher Wolf in their new book, Viral Hate: Containing Its Spread on the Internet. Their book explains why the best approach to online hate is a combination of education, digital literacy, user empowerment, industry best practices and self-regulation, increased watchdog / press oversight, social pressure and, most importantly, counter-speech. Foxman and Wolf also explain why — no matter how well-intentioned — legal solutions aimed at eradicating online hate will not work and would raise serious unintended consequences if imposed.

In striking this sensible balance, Foxman and Wolf have penned the definitive book on how to constructively combat viral hate in an age of ubiquitous information flows. Continue reading →

Alexander Howard has put together this excellent compendium of comments on Mike Rosenwald’s new Washington Post editorial, “Will the Twitter Police make Twitter boring?” I was pleased to see that so many others had the same reaction to Rosenwald’s piece that I did.

For the life of me, I cannot understand how anyone can equate counter-speech with “Twitter Police,” but that’s essentially what Rosenwald does in his essay. The examples he uses in his essay are exactly the sort of bone-headed and generally offensive comments that I would hope we would call out and challenge robustly in a deliberative democracy. But when average folks did exactly that, Rosenwald jumps to the preposterous conclusion that it somehow chilled speech. Stranger yet is his claim that “the Twitter Police are enforcing laws of their own making, with procedures they have authorized for themselves.” Say what? What laws are you talking about, Mike? This is just silly. These people are SPEAKING not enforcing any “laws.” They are expressing opinions about someone else’s (pretty crazy) opinions. This is what a healthy deliberative democracy is all about, bud!

Moreover, Rosenwald doesn’t really explain what a better world looks like. Is it one in which we all just turn a blind eye to what many regard as offensive or hair-brained commentary? I sure hope not!

I’m all for people vigorously expressing their opinions but I am just as strongly in favor of people pushing back with opinions of their own. You have no right to be free of social sanction if your speech offends large swaths of society. Speech has consequences and the more speech it prompts, the better.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.