Today is the 33rd anniversary of the Supreme Court’s landmark First Amendment decision, FCC v. Pacifica Foundation. By a narrow 5-4 vote in this 1978 decision, the Court held that the FCC could impose fines on radio and TV broadcasters who aired indecent content during daytime and early evening hours. The Court used some rather tortured reasoning to defend the proposition that broadcast platforms deserved lesser First Amendment treatment than all other media platforms. The lynchpin of the decision was the so-called “pervasiveness theory,” which held that broadcast speech was “uniquely pervasive” and an “intruder” in the home, and therefore demanded special, artificial content restrictions.

Back in 2008, when Pacifica turned 30, I penned a 6-part series critiquing the decision and discussing its impact on First Amendment jurisprudence:

In addition to those essays, I brought all my thinking together on this issue in a 2007 law review article, “Why Regulate Broadcasting: Toward a Consistent First Amendment Standard for the Information Age.” Importantly, this could be the last year we “celebrate” a Pacifica anniversary. Earlier this week, on the same day it handed down a historical video game free speech win, the Supreme Court announced that next term it will examine the constitutionality of FCC efforts to regulate “indecent” speech on broadcast TV and radio. Here’s hoping the Supreme Court takes the sensible step of undoing the unjust regulatory mess they created with Pacifica 33 years ago. Speech is speech is speech. Lawmakers should not be regulating it differently just because it’s on TV or radio instead of cable TV, satellite radio or TV, physical media, or the Internet. Continue reading →

It remains unclear how interested the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is in bringing a formal antitrust action against Google, but we at least know that inquiries have been made. I suspect these inquires are far more serious than whatever the agency is fishing for with its new Twitter inquires. After all, as I note in my latest Forbes column, “Google isn’t even a teenager yet (having only been founded in September 1998), but the firm’s rise has been meteoric and it has made a long list of enemies in the process. Practically every major player in the Digital Economy… is gunning for Google these days, both in the commercial and political marketplace.” In this sense, it’s not surprising the FTC might take a keen interest in the company with so many competitors complaining.

Still, I just can’t find much merit in an antitrust case against Google since, as I noted in my column, “The firm’s success seems tied to high quality products that users prefer over rival services. Importantly, barriers to entry are low: there’s nothing stopping new entrants from innovating and offering competing online services to match Google.”

Regardless, instead of arguing about the merits of an antitrust action against Google, let’s consider the more interesting, and I think intractable, question of remedies. Here’s what I had to say about that in my Forbes essay: Continue reading →

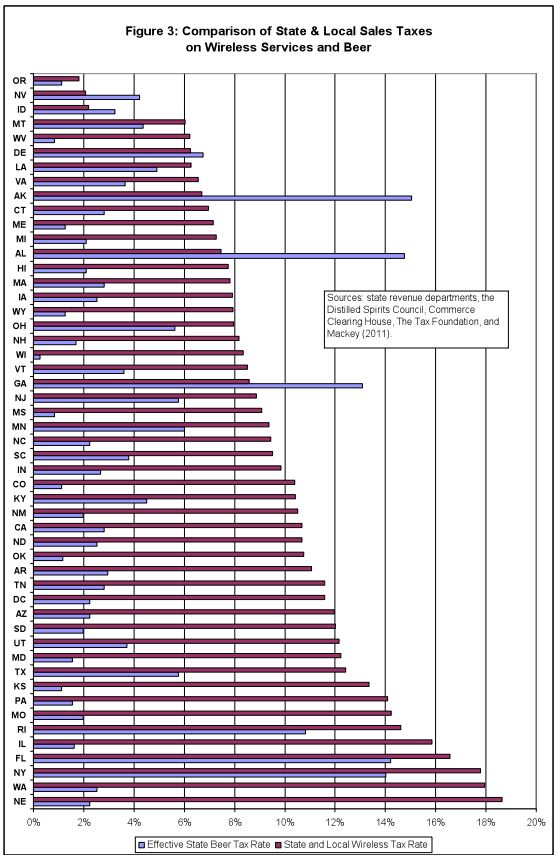

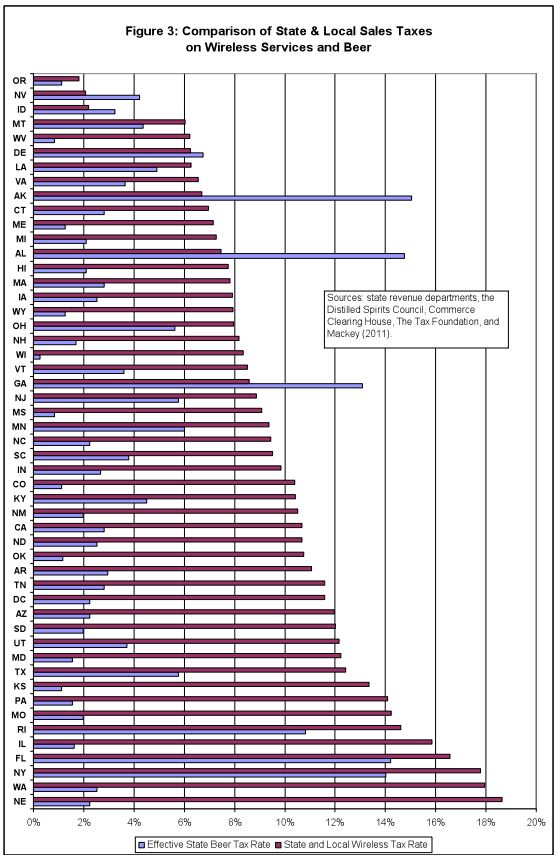

As we’ve noted here before, state and local politicians just love wireless taxes. They are going up, up, up. Dan Rothschild outlined this disturbing trend in his recent Mercatus Center paper making “The Case Against Taxing Cell Phone Subscribers,” and I discussed it in my recent Forbes essay lambasting the “Talking Tax.” Another new study by Glenn Woroch of the Georgetown University School of Business notes how “The ‘Wireless Tax Premium’ Harms American Consumers and Squanders the Potential of the Mobile Economy.” Woroch estimates that “the American consumer forgoes over $15 billion in surplus annually compared to when cell phones receive the

As we’ve noted here before, state and local politicians just love wireless taxes. They are going up, up, up. Dan Rothschild outlined this disturbing trend in his recent Mercatus Center paper making “The Case Against Taxing Cell Phone Subscribers,” and I discussed it in my recent Forbes essay lambasting the “Talking Tax.” Another new study by Glenn Woroch of the Georgetown University School of Business notes how “The ‘Wireless Tax Premium’ Harms American Consumers and Squanders the Potential of the Mobile Economy.” Woroch estimates that “the American consumer forgoes over $15 billion in surplus annually compared to when cell phones receive the

same tax treatment as other goods and service.” Read the entire study but I want to draw everyone’s attention to this chart that appears on page 7 of the report comparing state and local wireless taxes burdens to beer taxes. It really makes you realize just how drunk on wireless taxes are local lawmakers have become! [Click to enlarge. Red bar = wireless taxes.]

According to a report today from SAI Business Insider, “The Federal Trade Commission is actively investigating Twitter and the way it deals with the companies building applications and services for its platform.” Apparently the agency has reached out to some competing application / platform providers to ask questions about Twitter’s recent efforts to exert more control over the uses of its API by third parties. [The Wall Street Journal confirms the FTC’s interest in Twitter.]

It remains to be seen whether this leads to any serious regulatory action against Twitter by the FTC, but such a move wouldn’t necessarily be surprising considering the more activist tilt of the agency recently. It’s even less surprising considering that Columbia University law professor and prolific cyberlaw scholar Tim Wu was appointed as a senior advisor to the FTC earlier this year. When the announcement of Wu’s appointment was made, the Wall Street Journal kicked off an article with the warning, “Silicon Valley has a new fear factor.” It seems the Journal may have been on to something!

It’s impossible to know how much of an influence Tim Wu is having on the agency, but as I have noted here before, Prof. Wu is man with a healthy appetite for regulatory activism. [See all my essays about Wu’s work here.] Moreover, he’s a man who has already determined that Twitter is a “monopolist” in his November 13, 2010 Wall Street Journal op-ed, “In the Grip of the New Monopolists.”

That essay prompted a fiery response from me [“Tim Wu Redefines Monopoly“] as well as a far more reasoned essay by antitrust gurus Geoff Manne and Josh Wright [“What’s An Internet Monopolist? A Reply to Professor Wu.”] Prof. Wu was kind enough to swing by the TLF and respond to my criticisms in an essay “On the Definition of Monopoly,” which he said served as a “corrective” to my earlier essay [even though I continue to believe that what I said fairly reflected the last four decades of economic wisdom on competition policy and that it is Wu who is well off the reservation with his expansionist views of antitrust enforcement].

Regardless of what one thinks about that exchange, if the FTC is moving forward with a case against Twitter, three practical questions need to be considered: (1) What’s the relevant market? (2) Where’s the harm? and (3) What’s the remedy?

I’ll briefly discuss each question below but should also mention that I already explored many of these issues in my essay, “A Vision of (Regulatory) Things to Come for Twitter,” so I apologize in advance for the repetition. I will then discuss all this in the context of Tim Wu’s latest law review article on “Agency Threats” and what he approvingly refers to as regulatory “threat regimes.” Continue reading →

FCC Commissioner Robert M. McDowell delivered a terrific speech this week on “Technology and the Sovereignty of the Individual” at a broadband conference in Stockholm, Sweden. The speech serves as another reminder that McDowell is one of those ultimate rare birds: a regulator who is a first-rate intellectual thinker and a great champion of individual liberty. It’s a beautiful statement in defense of real Internet freedom. I can’t recall ever seeing another federal official cite the great Bruno Leoni in a speech!

FCC Commissioner Robert M. McDowell delivered a terrific speech this week on “Technology and the Sovereignty of the Individual” at a broadband conference in Stockholm, Sweden. The speech serves as another reminder that McDowell is one of those ultimate rare birds: a regulator who is a first-rate intellectual thinker and a great champion of individual liberty. It’s a beautiful statement in defense of real Internet freedom. I can’t recall ever seeing another federal official cite the great Bruno Leoni in a speech!

Here’s a sample of what Commissioner McDowell had to say:

To propel freedom’s momentum, policy makers should remember that, since their inception, the Internet and mobile connectivity have migrated further away from government control. As the result of longstanding international consensus, the Internet itself has become the greatest deregulatory success story of all time. To continue to promote freedom and prosperity, regulators should continue to rely on the “bottom up” nongovernmental Internet governance bodies that have a perfect record of keeping the ’Net working and open. We must heed the advice of leaders like Neelie Kroes, who has consistently called on regulators to “avoid over-hasty regulatory intervention,” and steer clear of “unnecessary measures which may hinder new efficient business models from emerging.” I couldn’t agree more. Changing course now could not only trigger an avalanche of international regulation, but it could halt the progress of freedom’s march as well.

Continue reading →

Yesterday’s 7-2 decision in Brown v. EMA [summaries here from me + Berin Szoka] was one of those historic First Amendment rulings that tends to bring out passions in people. You either loved it or hated it. But it’s sad to see some critics on the losing end of the case declaring that only greed could have possibly motivated the Court’s decision.

For example, California Senator Leland Yee, the author of the law that the Supreme Court struck down yesterday, obviously wasn’t happy about the outcome of the case. Neither was James Steyer, CEO of the advocacy group Common Sense Media, who has been a vociferous advocate of the California law and measures like it. What they had to say in response to the decision, however, was outlandish and juvenile. In essence, they both claimed that the Supreme Court only struck down the law to make video game developers and retailers happy.

“Unfortunately, the majority of the Supreme Court once again put the interests of corporate America before the interests of our children,” Leland Yee said in a post on his website yesterday. “As a result of their decision, Wal-Mart and the video game industry will continue to make billions of dollars at the expense of our kids’ mental health and the safety of our community. It is simply wrong that the video game industry can be allowed to put their profit margins over the rights of parents and the well-being of children.” Jim Steyer reached a similar conclusion: “Today’s decision is a disappointing one for parents, educators, and all who care about kids,” he said. “Today, the multi-billion dollar video game industry is celebrating the fact that their profits have been protected, but we will continue to fight for the best interests of kids and families.”

Mr. Yee and Mr. Steyer seem to be under the impression that the Court and supporters of its ruling in Brown cannot possibly care about children and that something sinister motivates our passion about the victory. Apparently we’re all just apparently in it to make video game industry fat cats and retailing giants happy! That’s a truly insulting position for Mr. Yee and Mr. Steyer to adopt. Perhaps it is just because they are sore about the outcome in the case that are adopting such rhetorical tactics. Regardless, I think they do themselves, their constituencies, and the public a great injustice by suggesting that only greed could possibly be motivating the outcome in this case. Continue reading →

[Cross-Posted at Truthonthemarket.com]

I did not intend for this to become a series (Part I), but I underestimated the supply of analysis simultaneously invoking “search bias” as an antitrust concept while waving it about untethered from antitrust’s institutional commitment to protecting consumer welfare. Harvard Business School Professor Ben Edelman offers the latest iteration in this genre. We’ve criticized his claims regarding search bias and antitrust on precisely these grounds.

For those who have not been following the Google antitrust saga, Google’s critics allege Google’s algorithmic search results “favor” its own services and products over those of rivals in some indefinite, often unspecified, improper manner. In particular, Professor Edelman and others — including Google’s business rivals — have argued that Google’s “bias” discriminates most harshly against vertical search engine rivals, i.e. rivals offering search specialized search services. In framing the theory that “search bias” can be a form of anticompetitive exclusion, Edelman writes:

Search bias is a mechanism whereby Google can leverage its dominance in search, in order to achieve dominance in other sectors. So for example, if Google wants to be dominant in restaurant reviews, Google can adjust search results, so whenever you search for restaurants, you get a Google reviews page, instead of a Chowhound or Yelp page. That’s good for Google, but it might not be in users’ best interests, particularly if the other services have better information, since they’ve specialized in exactly this area and have been doing it for years.

I’ve wondered what model of antitrust-relevant conduct Professor Edelman, an economist, has in mind. It is certainly well known in both the theoretical and empirical antitrust economics literature that “bias” is neither necessary nor sufficient for a theory of consumer harm; further, it is fairly obvious as a matter of economics that vertical integration can be, and typically is, both efficient and pro-consumer. Still further, the bulk of economic theory and evidence on these contracts suggest that they are generally efficient and a normal part of the competitive process generating consumer benefits. Continue reading →

On the podcast this week, Pamela Samuelson, the Richard M. Sherman Distinguished Professor of Law at Berkeley Law School, discusses her new article in the Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts entitled, Legislative Alternatives to the Google Book Settlement. Samuelson discusses the settlement, which was ultimately rejected, and highlights what she deems to be positive aspects. One aspect includes making out-of-print works available to a broad audience while keeping transaction costs low. Samuelson suggests encompassing these aspects into legislative reform. The goal of such reform would strike a balance that benefits rights holders, as well as the general public, while generating competition through implementation of a licensing scheme.

Related Links

To keep the conversation around this episode in one place, we’d like to ask you to comment at the web page for this episode on Surprisingly Free. Also, why not subscribe to the podcast on iTunes?

John Perry Barlow famously said that in cyberspace, the First Amendment is just a local ordinance. That’s still true, of course, and worth remembering. But at least today there is good news in the shire. The local ordinance still applies with full force, if only locally.

John Perry Barlow famously said that in cyberspace, the First Amendment is just a local ordinance. That’s still true, of course, and worth remembering. But at least today there is good news in the shire. The local ordinance still applies with full force, if only locally.

As I write in CNET this evening (see “Video Games Given Full First Amendment Protection“), the U.S. Supreme Court issued a strong and clear opinion today nullifying California’s 2005 law prohibiting the sale or rental to minors of what the state deemed “violent video games.” Continue reading →

Adam Thierer has already provided an excellent overview of the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, striking down a California law requiring age verification and parental consent for the purchase of “violent” videogames by minors. It’s worth calling attention to two key aspects of the decision.

First, the Supreme Court has clearly affirmed that the First Amendment applies equally to all media, including videogames and other interactive media. The Court has, in the past, often accorded lesser treatment to new media, as Cato’s excellent amicus brief explains [pp 3-15]. This approach, if applied consistently by the Court in the future, will ensure that free speech continues to be protected even as technology evolves in ways scarcely imaginable today.

Second, the Court correctly rejected California’s attempt to justify governmental paternalism as a supplement for parental responsibility [Brown at 15-17]. The existing content rating system and parental controls in videogame consoles already empower parents to make decisions about which games are appropriate for their children and their values. As in the Sorrell decision handed down last week, the Court has rejected what amounts to an opt-in mandate—this time, in favor of letting parents “opt-out” of letting their kids play certain games or rating levels rather than requiring that they “opt-in” to each purchase. This is the recurring debate about media consumption—from concerns over violent or offensive speech to those surrounding privacy. And once again, speech regulation must yield to the less-restrictive alternatives of empowerment and education.

Both these points were at the heart of the amicus brief I filed with the Supreme Court in this case last fall (press release), along with Adam (my former Progress & Freedom Foundation colleague) and Electronic Frontier Foundation Staff Attorney Lee Tien and Legal Director Cindy Cohn. Here’s the summary of our argument in that brief, which provides as concise an overview of our reasoning as we could manage, broken down into separate bullets with quotations referencing the Court’s decision on that point. As you’ll see, the Court’s decision reflected all our arguments except for one, which the Court’s decision did not reach. Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.