The left-leaning Air America Media radio network announced it was ceasing operations immediately today. It had been struggling for many years and appeared headed under many times before before being bailed out by various people. No doubt, many conservatives will rush to claim that the death of Air America is a sign that the political right is resurgent in America and that progressive viewpoints no longer have an audience. But I would beg to differ.

Don’t get me wrong, I was no fan of Air America. But the reality is that over-the-air terrestrial radio is an aging media platform that generally appeals to a more conservative-leaning and religious-oriented audience. That’s the primary reason conservative pundits like Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity are so dominant on the dial. Meanwhile, however, progressive voices have flocked to cyberspace and established a strong foothold here with an amazing array of blogs and websites dedicated to advancing their vision. Although conservatives have made some amazing strides online in recent years, they are still struggling to catch up with the likes of The Huffington Post, Daily Kos, and so on.

So, while many on the Right will be licking their chops today giddy with delight about the demise of Air America, the real question is: will they be able to catch up to the Left in cyberspace? Because Rush, Sean and talk radio ain’t gunna be around forever.

Of course, as a libertarian who has never once voted for a Democrat or Republican in my life, I really don’t give a damn who wins. We fans of real freedom — across-the-board economic and personal freedom, that is — have no media platform to call our own.

This morning at the Newseum in Washington, DC, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton delivered remarks on Internet freedom and the future of global free speech and expression. [Transcript is here + video.] It will go down as a historic speech in the field of Internet policy since she drew a bold line in the cyber-sand regarding exactly where the United States stands on global online freedom. Clinton’s answer was unequivocal: “Both the American people and nations that censor the Internet should understand that our government is committed to helping promote Internet freedom.” “The Internet can serve as a great equalizer,” she argued. “By providing people with access to knowledge and potential markets, networks can create opportunities where none exist.”

This morning at the Newseum in Washington, DC, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton delivered remarks on Internet freedom and the future of global free speech and expression. [Transcript is here + video.] It will go down as a historic speech in the field of Internet policy since she drew a bold line in the cyber-sand regarding exactly where the United States stands on global online freedom. Clinton’s answer was unequivocal: “Both the American people and nations that censor the Internet should understand that our government is committed to helping promote Internet freedom.” “The Internet can serve as a great equalizer,” she argued. “By providing people with access to knowledge and potential markets, networks can create opportunities where none exist.”

Unfortunately, however, “the same networks that help organize movements for freedom… can also be hijacked by governments to crush dissent and deny human rights.” Echoing Winston Churchill’s famous “iron curtain” speech, Sec. Clinton argued that “With the spread of these restrictive practices, a new information curtain is descending across much of the world.” She noted that virtual walls are replacing traditional walls in many nations as repressive regimes seek to squash the liberties of their citizenry. That’s why the Administration’s bold stand in favor of online freedom is so essential.

Importantly, Sec. Clinton made it clear that the Obama Administration is ready to commit significant resources to this effort. She said that, over the next year, the State Department plans to work with others to establish a standing effort to promote technology and will invite technologists to help advance the cause through a new “innovation competition” that will promote circumvention technologies and other technologies of freedom. Sec. Clinton also challenged private companies to stand up to censorship globally and challenge foreign governments when they demand controls on the free flow of information or digital technology.

That is particularly important because Secretary Clinton’s speech comes on the heels of the recent news that Google and at least 30 other Internet companies were the victims of cyberattacks in China, which raises profound questions about the future of online freedom and cybersecurity. Sec. Clinton’s remarks will make it clear to online operators that the U.S. government stands prepared to back them up when they challenge the censorial policies of repressive foreign regimes.

Continue reading →

Congress and the Federal Communications Commission periodically get upset over wireless phone early termination fees. The latest uproar has occurred during the past couple months in response to Verizon’s doubling of the early termination fee on “smart” devices. The fee falls by $10 per month, leaving s $120 early termination fee in the last month of a two-year contract.

Policymakers still have not gotten the message that they cannot really do much about this “problem” unless they comprehensively regulate wireless rates and terms of service. (I would not recommend this, since a competitive wireless market has brought us rate reductions that even perfectly-functioning regulation would be unlikely to achieve. ) Attempts to poke and prod early termination fees are like the carnival game “whack-a-mole.” As soon as you whack one mole with a stick, another one pops up out of another hole.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) is taking another whack. In 2007, she introduced legislation requiring wireless companies to prorate early termination fees “in a manner that reasonably links the fee to recovery of the cost of the device or other legitimate business expenses.” Coincidentally, the major carriers promised to prorate their fees at about the same time her bill got a hearing. Then last November, up popped a mole from Verizon’s hole. Early termination fees for smart devices are prorated, but doubled. Now the good senator is whacking away at that mole with legislation that requires wireless companies to prorate early termination fees AND mandates that the early termination fee cannot exceed the size of the subsidy the carrier is giving the consumer on the phone.

Smart whack, huh? Doesn’t cost-based regulation of early termination fees eliminate the loophole (oops, mole-hole)?

Not necessarily. In the first place, the legislation could create an accounting nightmare with plenty of opportunities for companies to game the system, especially if they offer different subsidies on different phones. Recall that the original impetus for breaking up the old AT&T landline monopoly was that AT&T was gouging consumers by charging them inflated prices to lease equipment manufactured by its subsidiary, Western Electric. With the AT&T breakup, the government essentially gave up on managing that problem and completely prohibited the monopoly local phone companies from manufacuring equipment. I think George Santayana just left me a voice mail. Even if the game board is restricted to early termination fees, we’ll soon see uglier, nastier moles emerge from uglier, nastier holes.

But the wireless phone contract is about more than early termination fees. Even if policymakers succeed in imposing effective, cost-based regualtion on early termination fees, wireless companies can still change other terms of the contract to compensate for any revenue losses. The law must have a truly long arm to reach the diverse array of rodents that will scurry forth from diverse orifices.

Stay tuned for the next whack.

No one disputes that a key goal of the FCC is to help foster diversity in, and minority access to, channels of communication. In practice, this all too often has been interpreted to mean ownership limits, set-asides, preferences and other mandates imposed by the Commission. Usually lost in the heated debates is the fact that ill-considered regulation itself can impede minority access and diversity.

In comments filed last week, a group of sixteen minority and civil rights organizations — ranging from the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law to the National Conference of Black Mayors — argue that net neutrality regulation may do just that. “[T]his proceeding implicates one of the most important civil rights issues of our time,” the comments –written by David Honig of the Minority Media and Telecommunications Council — assert. Continue reading →

Originally published in Space News on January 11, 2010

In December, Barack Obama accepted the Nobel Peace Prize, only the third sitting U.S. president to win—and the fourth ever. The award was announced before Obama had finished eight months in office. Indeed, the February Feb. 1, 2009, nomination deadline passed just 13 days after his inauguration.

Was there something we missed in that brief span that could match Woodrow Wilson’s presiding over the settlement of World War I, or the founding of the League of Nations? Or Teddy Roosevelt’s opening of the International Court of Arbitration and ending Japan’s bloody 1905 war with Russia? Or Jimmy Carter’s three decades of peace-making and development work? Has Obama already done more to abolish nuclear weapons than President Ronald Reagan, whose anti-nuclear crusade and actual warhead reductions were never celebrated with a Peace Prize?

There is another president who should have received the Prize long ago for stabilizing a world teetering on the brink of nuclear war. After leading Allied forces to victory over Nazi Germany, Dwight D. Eisenhower negotiated a cease-fire to Harry Truman’s war in Korea, resisted calls for American intervention in Vietnam, and single-handedly defused the 1956 Suez Crisis. His warnings about the “military-industrial complex” did more to check the growth of the national security state than all past or future peace marches combined.

But only recently has Eisenhower’s greatest achievement become clear: ensuring the right to peaceful uses of outer space.

Just as maritime commerce has thrived on “freedom of the high seas” for centuries, “freedom of space” has allowed the development of a $200 billion satellite industry that has interconnected the globe in a web of voice, video and data, and provided critical weather and climate monitoring. By ensuring that nations cannot block access to space with territorial claims, international law has prevented governments from stifling the birth of a truly spacefaring civilization. Continue reading →

Over this past week, a lot of people were making hay over this recent ReadWriteWeb story, “Facebook’s Zuckerberg Says The Age of Privacy is Over.” Seems that some people were taking issue with Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg’s suggestion that Facebook’s recent site policy changes, which generally encouraged more sharing or information, were in line with public expectations. Most people put words in Zuckerberg’s mouth and accused him of saying that “privacy is over” or that he claimed he “is a prophet,” neither of which he actually said. But let’s ignore the fact that some people made stuff up and get back to the point: What set people off about Facebook’s recent site changes and Zuckerberg’s rationalization of them?

I think it goes back to the fact that a lot of people want to have their cake and eat it too. “It is the paradox of the cyber era,” notes Washington Post columnist Michael Gerson: We are “a nation of exhibitionists demanding privacy.” Indeed, that’s true, but there’s a good reason why this so-called “privacy paradox” exists. As Larry Downes, author of the brilliant new book, The Laws of Disruption, argues:

People value their privacy, but then go out of their way to give it up. There’s nothing paradoxical about it. We do value privacy. It’s just that we’re willing to trade it for services we value even more. Consumers intuitively look at the information being requested and decide whether the value they receive for disclosing it is worth the cost of their privacy. (p. 80)

That’s exactly right. When confronted with real world choices about privacy and information sharing, we often are willing to accept some trade-offs in exchange for something of value. But when we are asked about this process we are loathe to admit that we would willingly engage in such privacy-for-services trade-offs even if we do it every day of our lives. As Michael Arrington of TechCrunch rightly points out:

Continue reading →

Can the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) just do anything it wants? If it wants to bring the entire Internet under its thumb, or regulate any speech uttered over electronic media, can it just do so on a whim? The agency’s recent actions on the Net neutrality and free speech fronts seems to suggest that the agency thinks so.

I don’t need to rehash here what the FCC has been up to on the Net neutrality front. Most everyone is familiar with how the agency has essentially been trying to invent its authority to regulate out of thin air. If you want the whole ugly history of how this charade has unfolded over past few years, I encourage you to read these amazing comments filed today in the FCC’s net neutrality NPRM proceeding by my PFF colleague Barbara Esbin. Barbara simply demolishes the FCC’s argument that it can do anything it wants under the guise of its “ancillary jurisdiction.” As Barbara argues in her comments, the FCC’s position “is akin to saying that the FCC can regulate if its actions are ancillary to its ancillary jurisdiction, and that is one ancillary too many.” She notes that:

The proposed rules regulating the services and network management practices of broadband Internet providers must rest, if at all, on the Commission‘s implied or ancillary jurisdiction and the NPRM fails to provide a basis upon which the exercise of such jurisdiction can be considered lawful.

She shows how farcical it is for the FCC to concoct its supposed authority to regulate from provisions of the Communications Act that have nothing whatsoever to do with Net neutrality or even expanding regulation in general. Specifically, the agency’s reliance on sections 230(b) and 706(a) of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 is completely outlandish. Anyone who knows a lick about telecom law and the nature of those two sections understands they were never intended to serve as the basis of an expansive new regulatory regime for the Internet. As Barbara puts it:

This exercise—searching for snippets and threads of regulatory authority over a communications medium as significant as the Internet in multiple, unrelated statutory provisions—should signal to the Commission that no credible source of authority to regulate Internet services exists.

All I have to say is, thank God for checks and balances. I believe the courts will put a stop to this nonsense, but it will take some time. Until then, I suppose the FCC will continue to act like a rogue agency, hell-bent and tossing the constitution to the wind and concocting asinine theories about why they should be allowed to do anything they want. But there are signs that the courts are ready to start holding the FCC more accountable. Continue reading →

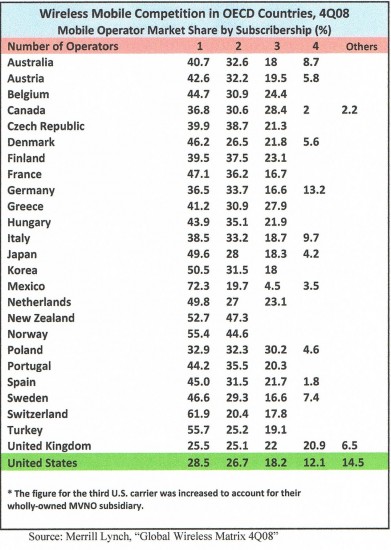

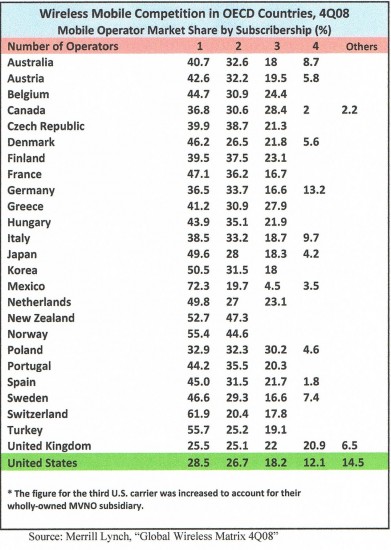

In my researching the wireless competitive picture for my comments on the FCC Network Neutrality NPRM, one of my contacts was kind enough to point me to a Bank of America/Merrill Lynch paper that used the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) to compare the market concentration of wireless service providers in the 26 Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) countries. HHI is one of the metrics used by the Department of Justice to determine market concentration. It is calculated by squaring the market share of each firm competing in the market and then summing the resulting numbers. For example, for a market consisting of four firms with shares of 30, 30, 20, 20 percent, the HHI is 2600 (302 + 302 + 202 + 202 = 2600). The higher the number, the greater the market concentration. When the formula is applied to the U.S. wireless market share percentages determined by Bank of America/Merrill Lynch (28.5, 26.7, 18.2. 12.1 and 14.5), the U.S. HHI is the smallest at 2213. This number is substantially less than the HHIs for all the other OECD companies with the exception of the U.K. Otherwise, no other HHI is under 2900.

Here’s the OECD market share data for Q4 2007 as it appears in the Bank of America/Merrill Lynch’s Global Wireless Matrix.

Continue reading →

Continue reading →

Yesterday’s bombshell announcement that Google is prepared to pull out of China rather than continuing to cooperate with government Web censorship was precipitated by a series of attacks on Google servers seeking information about the accounts of Chinese dissidents. One thing that leaped out at me from the announcement was the claim that the breach “was limited to account information (such as the date the account was created) and subject line, rather than the content of emails themselves.” That piqued my interest because it’s precisely the kind of information that law enforcement is able to obtain via court order, and I was hard-pressed to think of other reasons they’d have segregated access to user account and header information. And as Macworld reports, that’s precisely where the attackers got in:

Yesterday’s bombshell announcement that Google is prepared to pull out of China rather than continuing to cooperate with government Web censorship was precipitated by a series of attacks on Google servers seeking information about the accounts of Chinese dissidents. One thing that leaped out at me from the announcement was the claim that the breach “was limited to account information (such as the date the account was created) and subject line, rather than the content of emails themselves.” That piqued my interest because it’s precisely the kind of information that law enforcement is able to obtain via court order, and I was hard-pressed to think of other reasons they’d have segregated access to user account and header information. And as Macworld reports, that’s precisely where the attackers got in:

That’s because they apparently were able to access a system used to help Google comply with search warrants by providing data on Google users, said a source familiar with the situation, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak with the press.

This is hardly the first time telecom surveillance architecture designed for law enforcement use has been exploited by hackers. In 2005, it was discovered that Greece’s largest cellular network had been compromised by an outside adversary. Software intended to facilitate legal wiretaps had been switched on and hijacked by an unknown attacker, who used it to spy on the conversations of over 100 Greek VIPs, including the prime minister.

As an eminent group of security experts argued in 2008, the trend toward building surveillance capability into telecommunications architecture amounts to a breach-by-design, and a serious security risk. As the volume of requests from law enforcement at all levels grows, the compliance burdens on telcoms grow also—making it increasingly tempting to create automated portals to permit access to user information with minimal human intervention.

The problem of volume is front and center in a leaked recording released last month, in which Sprint’s head of legal compliance revealed that their automated system had processed 8 million requests for GPS location data in the span of a year, noting that it would have been impossible to manually serve that level of law enforcement traffic. Less remarked on, though, was Taylor’s speculation that someone who downloaded a phony warrant form and submitted it to a random telecom would have a good chance of getting a response—and one assumes he’d know if anyone would.

The irony here is that, while we’re accustomed to talking about the tension between privacy and security—to the point where it sometimes seems like people think greater invasion of privacy ipso facto yields greater security—one of the most serious and least discussed problems with built-in surveillance is the security risk it creates.

Cross-posted from Cato@Liberty.

by Adam Thierer & Berin Szoka, Progress Snaphot 6.1

Stephanie Clifford of the New York Times posted a very interesting article this week summarizing a recent “on-the-record chat” the Times staff had with Federal Trade Commission (FTC) chairman Jon Leibowitz and FTC Bureau of Consumer Protection chief David Vladeck. The interview [discussed by Braden here] is profoundly important in that it reveals an alarming disconnect regarding the relationship between “privacy” regulation and the future of media, which were the subjects of their discussion with Times staff. Namely, Leibowitz and Vladeck apparently fail to appreciate how the delicate balance between commercial advertising and journalism is at risk precisely because of the sort of regulations they apparently are ready to adopt. Because the value of online advertising depends on data about its effectiveness and consumers’ likely interests, and because advertising is indispensable to funding media, what’s ultimately at stake here is nothing short of the future of press freedom.

The “Day of Reckoning” Is Upon Us

Leibowitz and Vladeck spend the first half of The Times interview wringing their hands about “privacy policies,” the declarations made by websites and advertising networks about their data collection and use practices (for which the FTC can and must hold them accountable). But the two feel that privacy policies don’t adequately inform consumers. Chairman Leibowitz claims that online companies “haven’t given consumers effective notice, so they can make effective choices.” And Mr. Vladeck states that advise-and-consent models “depended on the fiction that people were meaningfully giving consent.” But he and the FTC seem ready to abandon the notice and choice model because the “literature is clear” that few people read privacy policies, Vladeck told the Times. He and Leibowitz continue:

“Philosophically, we wonder if we’re moving to a post-disclosure era and what that would look like,” Mr. Vladeck said. “What’s the substitute for it?” He said the commission was still looking into the issue, but it hoped to have an answer by June or July, when it plans to publish a report on the subject. Mr. Leibowitz gave a hint as to what might be included: “I have a sense, and it’s still amorphous, that we might head toward opt-in,” Mr. Leibowitz said.

This clearly foreshadows the regulatory endgame we have long suspected was coming. When the FTC released its “Self-Regulatory Principles for Online Behavioral Advertising” eleven months ago, we asked: “What’s the Harm & Where Are We Heading?” Their answers to both questions have become clearer with each new calculated comment—all apparently intended to slowly “turn up the heat” on the advertising industry so that the proverbial frog will stay in the pot until the water finally boils. Leibowitz’s FTC has simply dodged the “harm” question with a four-part strategy: Continue reading →

This morning at the Newseum in Washington, DC, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton delivered remarks on Internet freedom and the future of global free speech and expression. [

This morning at the Newseum in Washington, DC, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton delivered remarks on Internet freedom and the future of global free speech and expression. [

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.