I’m delighted to report that the White House’s web site, Whitehouse.gov, has begun posting the bills Congress sends down Pennsylvania Avenue so they can get a final public review. This actually began some time ago, but a link from the home page now directs visitors (and search engines) to the bills that await the president’s signature.

This is an important step toward fulfilling President Obama’s campaign promise to post the bills he receives from Congress online for five days before he signs them.

Take a look for yourself: On the Whitehouse.gov home page, a link at the bottom of the “Featured Legislation” column says “Comment on Pending Legislation.”

Currently, four bills are listed there, arranged in order by the dates they were posted. The final language isn’t posted at the link, and it takes a little sophistication to find the final version at the linked-to page on the Thomas system, but this is substantial progress.

Kudos to the White House for moving toward full implementation of President Obama’s Sunlight Before Signing promise!

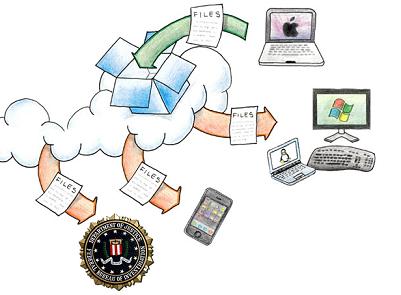

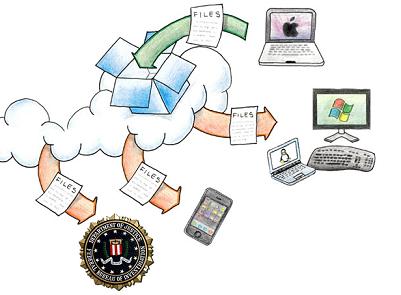

A colleague apparently suggested that the nice people at Dropbox should email me with an invitation to use their services. The concept appears simple enough—remote storage that makes users’ files available on any laptop, desktop, or phone.

A colleague apparently suggested that the nice people at Dropbox should email me with an invitation to use their services. The concept appears simple enough—remote storage that makes users’ files available on any laptop, desktop, or phone.

I was intrigued by it because it’s a discrete example of a “cloud” computing service. How do they handle some of the key privacy challenges? A cloud over remote computing and storage is the likelihood that governments will use it to discover private information with dubious legal justification, or without any at all. (Businesses likewise can rightly worry that competitors working with governments might access trade secrets.)

Well, it turns out they don’t handle these challenges. Dropbox is a privacy black box.

I homed right in on their “Policies” page, looking for assurance that they would protect the legal rights of users to control information placed in the care of their service. There’s precious little to be found.

There’s no promise that they would limit information they share with authorities to what is required by valid legal process. There’s no promise that they would notify users of a warrant or subpoena. They do reserve the right to monitor access and use of their site “to comply with applicable law or the order or requirement of a court, administrative agency or other governmental body.”

Is there protection in the fact that files are stored encrypted on their service? The site—though not the terms of service—says “All files stored on Dropbox servers are encrypted (AES-256) and are inaccessible without your account password.” Not if Dropbox is willing to monitor the use of the site on behalf of law enforcement. They can simply gather your password and hand it over.

National Security Letter authority and the impoverished “third party doctrine” in Fourth Amendment law puts cloud-user privacy on pretty weak footing. Dropbox’s policies do nothing to shore that up. It’s not alone, of course. It’s just a nice discrete example of how “the cloud” exposes your data to risks that local storage doesn’t.

There are a few other problems with it. They don’t promise to notify users directly of changes to the privacy policy. (“[W]e will notify you of any material changes by posting the new Privacy Policy on the Site…”) And they reserve the right to change their terms of service any time—without giving you the right to access and remove your files. When they decide to make their free service a paid service, they could hold your files hostage unless you sign up for x years. Data liberation is an important term of services like this.

Golly, even as I’ve been writing this, friends have tweeted that they like Dropbox. It sounds like a fine service for what it is. I just wouldn’t put anything on there that you wanted to keep private or that you really wanted to be sure you could access.

PFF has just released the transcript of an excellent panel discussion I moderated last week entitled, “Let’s Make a Deal: Broadcasters, Mobile Broadband, and a Market in Spectrum.” As I’ve mentioned here before, one of the hottest issues in DC right now is the question of broadcast TV spectrum reallocation. Blair Levin, who serves as the Executive Director of the Omnibus Broadband Initiative at the Federal Communications Commission, recently raised the possibility of reallocating a portion of broadcast television spectrum for alternative purposes, namely, mobile broadband. Such a “cash-for-spectrum” swap would give mobile broadband providers to spectrum they need to roll out next generation wireless broadband networks while making sure broadcaster receive compensation for any spectrum they hand over. The FCC just recently released a public notice on “Data Sought on Users of Spectrum,” (NBP Public Notice # 26) that looks into the matter. “This inquiry,” the agency says,” takes into account the value that the United States puts on free, over-the-air television, while also exploring market-based mechanisms for television broadcasters to contribute to the broadband effort any spectrum in excess of that which they need to meet their public interest obligations and remain financially viable.” Meanwhile, the House Energy and Commerce Communications Subcommittee is set to hold a hearing on the issue next Tuesday.

PFF’s panel discussion on this issue featured an all-star cast of characters, including opening remarks by Blair Levin, and a terrific discussion ensued. [You can hear the full audio from the event here.] Down below I have highlighted some of the major points each speaker made during the discussion and also embedded the complete transcript in a Scribd reader. Also, just a reminder that my PFF colleague Barbara Esbin and I authored a short paper on this issue recently: “An Offer They Can’t Refuse: Spectrum Reallocation That Can Benefit Consumers, Broadcasters & the Mobile Broadband Sector.”

Continue reading →

Yesterday marked the beginning of the third annual US-China Internet Industry Forum (held this year in SF). The purpose of the gathering is to increase mutual understanding of key business and policy issues in China and the US. It is an invite-only event, so I was excited to be there with top government and technology leaders such as Wikipedia’s Jimmy Wales, Sina.com’s Charles Cao, Harvard law prof John Palfrey (author of Born Digital – loved that book), Microsoft’s Chief Research and Strategy Officer Craig Mundie, Google’s Chief Economist Hal Varian, Baidu’s COO Ye Peng, The FBI’s Jeffrey Troy, China’s Deputy Director of the Internet, Liu Zhengrong, and a bunch of others (eBay, Yahoo, Intel, Facebook, etc). The main topics of discussion were intellectual property, online child protection, and cybercrime.

What struck me most about the discussions was the degree of concern the Chinese attendees showed for intellectual property. Now that China is moving towards a knowledge-based economy, they are realizing that it is in their best interests to do a better job of protecting IP. Most Americans probably don’t realize it, but there is a vibrant start-up community in China and it won’t be long before we start to see more innovation coming from that country.

The event was co-hosted by Microsoft and the Internet Society of China and co-sponsored by Google, eBay, Intel, About.com, Verisign, Akamai, Yahoo, People.com, Xinhuanet.com, China.com.cn, CCTV.com, SOHU.com, Netease.com and Baidu.com.

This morning the Federal Trade Commission released its report on kids and virtual worlds. You can read the report, entitled Virtual Worlds and Kids: Mapping the Risks, here. (I’ve posted similar thoughts over at Terra Nova, apologies for the cross-post).

What initially strikes me about the report is the distance between how the report’s being billed and what it actually says. The billing of the report—and thus the likely media tagline—is that the “FTC Report Finds Sexually and Violently Explicit Content in Online Virtual Worlds Accessed by Minors.” But a more accurate statement would be “FTC Report Finds Surprisingly Little Sexually and Violently Explicit Content in Online Virtual Worlds Accessed by Minors, Especially Compared to What Minors Can Find on the Internet.”

The Commission found at least one (really? that’s all?) instance of explicitly violent OR sexual content in a significant percentage of the virtual worlds it examined—and that includes user chat, but in general it didn’t find many such instances per world. So to be counted in the study as a virtual world that contains explicit violent or sexual content, the researchers just had to find one instance of chat in which someone said something violent or sexually oriented (which of course includes the scatalogical as well as the sexual). The point is, it appears to me that they went looking for anything and didn’t find much. Far from being seen as an indictment of virtual worlds as dangerous for kids, this seems to me to be quite positive for virtual worlds, especially as compared to the internet at large. I’m relying on the following language from the report:

Despite this seemingly high statistic [the Commission found at least one instance of sexually or violently explicit content in 19 out of 27 worlds], the Commission found very little explicit content in most of the virtual worlds surveyed, when viewed by the actual incidence of such content.

And:

Of [the 14 virtual worlds open to children under 13], the Commission found at least one instance of explicit content on seven of them. Significantly, however, with the exception of one world, Bots, all of the explicit content observed in the child-oriented worlds occurred when the Commission’s researchers visited those worlds as teen or adult registrants, not when visiting the worlds as children under age 13.

I think the study said some interesting things, and there is some strong analysis, but the reception the report will get is, I bet, far removed from what the report actually says.

At Berin’s suggesting, cross-posting from Cato@Liberty:

I’ve just gotten around to reading Orin Kerr’s fine paper “Applying the Fourth Amendment to the Internet: A General Approach.” Like most everything he writes on the topic of technology and privacy, it is thoughtful and worth reading. Here, from the abstract, are the main conclusions:

First, the traditional physical distinction between inside and outside should be replaced with the online distinction between content and non-content information. Second, courts should require a search warrant that is particularized to individuals rather than Internet accounts to collect the contents of protected Internet communications. These two principles point the way to a technology-neutral translation of the Fourth Amendment from physical space to cyberspace.

I’ll let folks read the full arguments to these conclusions in Orin’s own words, but I want to suggest a clarification and a tentative objection. The clarification is that, while I think the right level of particularity is, broadly speaking, the person rather than the account, search warrants should have to specify in advance either the accounts covered (a list of e-mail addresses) or the method of determining which accounts are covered (”such accounts as the ISP identifies as belonging to the target,” for instance). Since there’s often substantial uncertainty about who is actually behind a particular online identity, the discretion of the investigator in making that link should be constrained to the maximum practicable extent.

The objection is that there’s an important ambiguity in the physical-space “inside/outside” distinction, and how one interprets it matters a great deal for what the online content/non-content distinction amounts to. The crux of it is this: Several cases suggest that surveillance conducted “outside” a protected space can nevertheless be surveillance of the “inside” of that space. The grandaddy in this line is, of course, Katz v. United States, which held that wiretaps and listening devices may constitute a “search” though they do not involve physical intrusion on private property. Kerr can accomodate this by noting that while this is surveillance “outside” physical space, it captures the “inside” of communication contents. But a greater difficulty is presented by another important case, Kyllo v. United States, with which Kerr deals rather too cursorily.

Continue reading →

One of the more troubling aspects of the contentious debate over Net neutrality regulation is the way some proponents have sought to cast Net neutrality as “the Internet’s First Amendment.” As a die-hard free speech advocate, I find this truly outrageous and a complete contortion of the true purpose of the First Amendment. As I have argued here before, it is incredibly dangerous thinking that puts our real First Amendment liberties at stake by empowering a regulatory agency with more means of controlling online speech and expression. Simply stated, the Internet’s First Amendment is the First Amendment, not some new, top-down, heavy-handed regulatory regime that puts the Federal Communications Commission in control of the Digital Economy.

On this point, I wanted to bring two things to your attention. The first is an outstanding address delivered today by Kyle McSlarrow, President & CEO of the National Cable & Telecommunications Association, at a Media Institute event here in Washington, DC. And the second is this new paper by my PFF colleague Barbara Esbin.

McSlarrow’s speech was entitled, “Net Neutrality: First Amendment Rhetoric in Search of the Constitution” and it squarely addressed the fundamental fallacy set forth by the Net neutralitistas when it comes to the First Amendment. “Whatever our present-day policy disagreements about net neutrality, or even differing politics, let’s not forget that the First Amendment is framed as a shield for citizens, not a sword for government,” he argued. “By its plain terms and history, the First Amendment is a limitation on government power, not an empowerment of government,” McSlarrow said. “And… if there’s one thing the Supreme Court has made clear, it’s that rules that directly restrict protected speech cannot be justified by a government interest that is merely hypothetical.”

Absolutely correct. And these views are buttressed by the comments of Barbara Esbin in her new paper, in which she argues that “Net Neutrality is not the First Amendment for the Internet.” She continues: Continue reading →

Wine lovers in 37 states can now order wine online from out-of-state sellers and have it shipped to their homes. But if you’re thinking of laying in a nice California red to celebrate the holidays, you could have to pay more if your state law only allows you to order online from wineries.

This topic came up yesterday while I was testifying before the Tennessee General Assembly’s Joint Study Committee on Wine in Grocery Stores. Rick Jelvosek, a Tennessee wine consumer who testified on behalf of Tennessee Consumers for Fair Wine Laws, asked lawmakers to allow out-of-state retailers to ship to Tennessee consumers, so consumers could have access to a greater variety of wines than they can get from the 160 wineries currently licensed to ship wine to consumers. (Video of the hearing is available here.)

Letting retailers ship directly to consumers also lets consumers save money. In 2002 and 2004, Alan Wiseman (now at Ohio State University) and I gathered data on the prices and availability of a sample of popular wines from online sellers and in Nothern Virginia retail stores. For most bottles, the lowest online price was offered not by the winery, but by a retailer. Usually a California retailer offered the lowest price, but for a few bottles the low-price retailer was in Illinois, New York, Washington DC, Missouri, or Texas. We suspect the reason is that California allows wineries to bypass wine wholesalers and sell directly to retailers if they choose. The tabulations are in this article.

Wall Street Journal columnist Holman Jenkins has a new column up this morning about the ongoing battle over broadcast television spectrum reallocation. [“The Rabbit-Ear Wars.”] It discusses the plan being floated by FCC “broadband czar” Blair Levin, who serves as the Executive Director of the Omnibus Broadband Initiative at the Federal Communications Commission. Levin has raised the possibility of reallocating a portion of broadcast television spectrum for alternative purposes, namely, mobile broadband. Such a “cash-for-spectrum” swap would give mobile broadband providers to spectrum they need to roll out next generation wireless broadband networks while making sure broadcaster receive compensation for any spectrum they hand over. The FCC just recently released a public notice on “Data Sought on Users of Spectrum,” (NBP Public Notice # 26) that looks into the matter. “This inquiry,” the agency says,” takes into account the value that the United States puts on free, over-the-air television, while also exploring market-based mechanisms for television broadcasters to contribute to the broadband effort any spectrum in excess of that which they need to meet their public interest obligations and remain financially viable.”

Holman Jenkins argues that the issue is incredibly contentious and likely to engender a great deal of political wrangling. “The spectrum puzzle won’t be solved by the clean and simple deal the agency envisioned,” he says. That’s true, but I think the FCC still deserve some credit for at least starting the discussion. As my PFF colleague Barbara Esbin and I noted in our recent paper, “An Offer They Can’t Refuse: Spectrum Reallocation That Can Benefit Consumers, Broadcasters & the Mobile Broadband Sector,” [PDF], it’s hard to see what is wrong with letting broadcasters hear offers of cash for their spectrum! That being said, they should have their hands forced (to give up the spectrum, that is). I think Jenkins generally gets it right when he says: Continue reading →

A colleague apparently suggested that the nice people at

A colleague apparently suggested that the nice people at  The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.