Libertarian folk-hero Rep. Ron Paul has apparently convinced (WSJ) House Financial Services Committee Chairman Barney Frank to implement his proposal (HR 1207) for an audit of the Federal Reserve by the end of 2010. Paul’s Bill would expand existing audits considerably because, under current law, the Government Accountability Office,

can’t review most of the Fed’s monetary policy actions or decisions, including discount window lending (direct loans to financial institutions), open-market operations and any other transactions made under the direction of the Federal Open Market Committee. It also can’t look into the Fed’s transactions with foreign governments, foreign central banks and other international financing organizations…

While the bill only seeks a one-time audit, [Paul] said he wants the Fed to be audited at least annually with the report — and details of its transactions — disclosed publicly.

I’d like to up the ante: Let’s make sure that any data disclosures are made in eXtensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL), as Mark Cuban and our own Jim Harper have previously suggested. Such machine-readable disclosures would be much more useful, because the data could be analyzed or “mashed-up” with other data sets to answer questions we might not even be able to formulate today.

Gordon Crovitz has a fascinating piece in the WSJ today entitled, Diplomacy in the Age of No Secrets, discussing the Internet’s role in increasing public scrutiny of the deal negotiated by Scottish officials, British diplomats and the Libyan government over the release of Lockerbie bomber Abdel Basset al-Megrahi.

Diplomacy was once satirically defined as the patriotic art of lying for one’s country. This approach is hard to sustain in a world that demands transparency. For diplomats, there’s no negotiating around the fact that confidential deals today could be headlines tomorrow.

I can’t wait to see how the State Department to this new reality!

The D.C. Circuit has struck down as arbitrary and capricious the FCC’s “cable cap.” The cap prevented a single cable operator from serving more than 30% of U.S. homes—precisely the same percentage limit struck down by the court in 2001. The court ruled that the FCC had failed to demonstrate that “allowing a cable operator to serve more than 30% of all cable subscribers would threaten to reduce either competition or diversity in programming.”

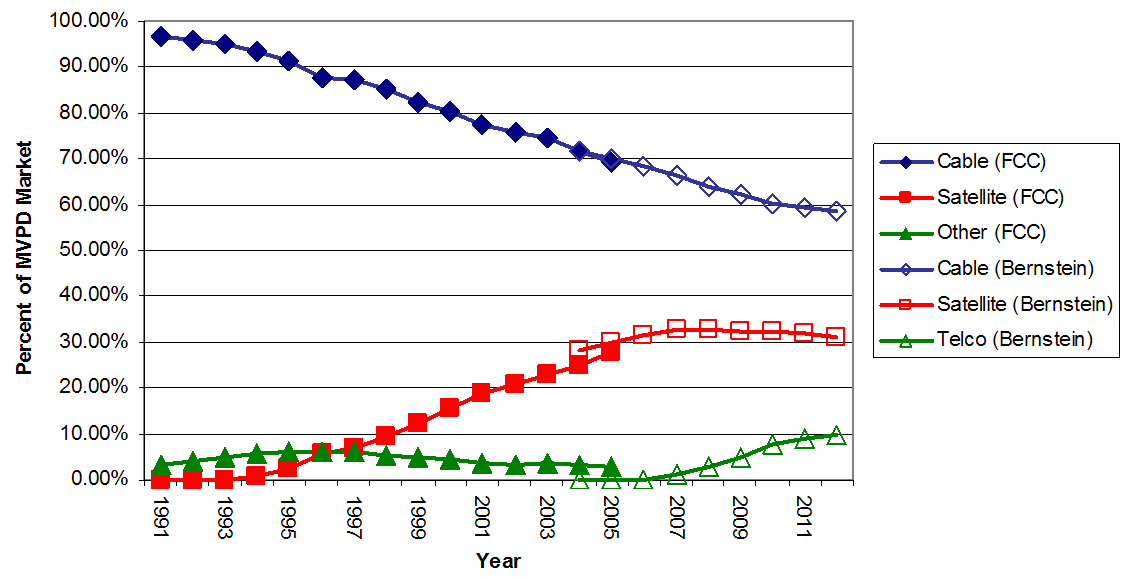

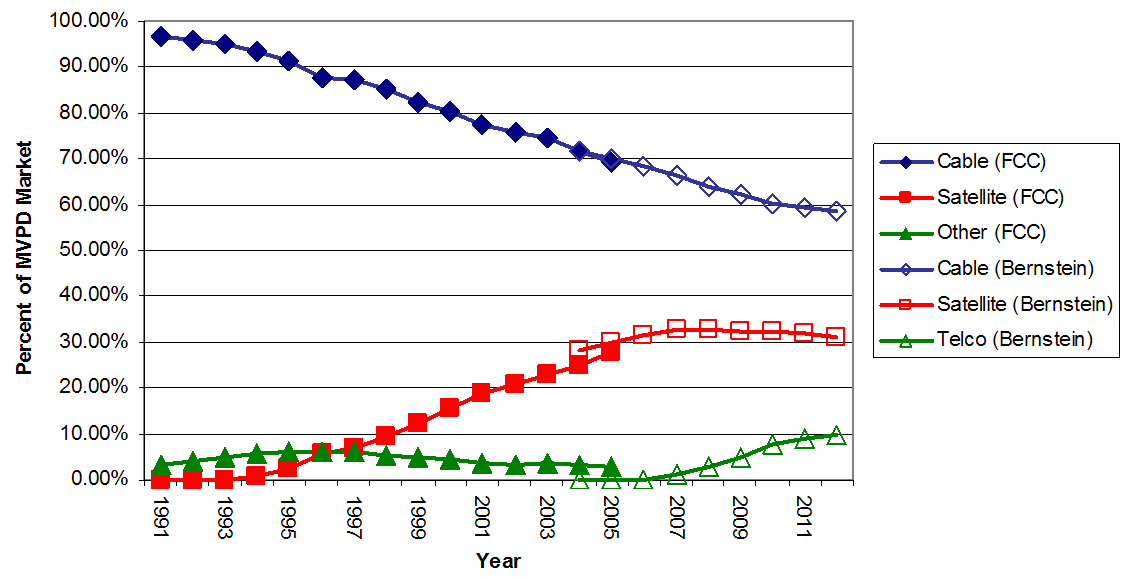

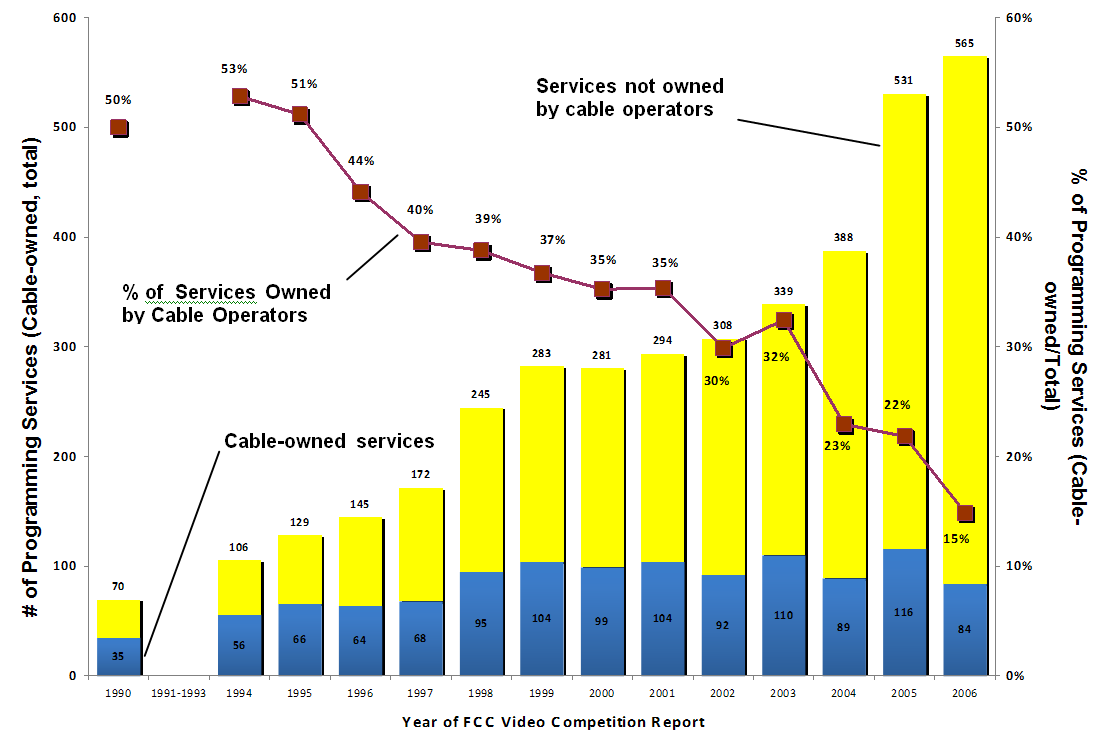

The court’s decision rested on the two critical charts (both generated by my PFF colleague Adam Thierer in his excellent Media Metrics special report) at the heart of the PFF amicus brief I wrote with our president, Ken Ferree:

First, the record is replete with evidence of ever increasing competition among video providers: Satellite and fiber optic video providers have entered the market and grown in market share since the Congress passed the 1992 Act, and particularly in recent years. Cable operators, therefore, no longer have the bottleneck power over programming that concerned the Congress in 1992.

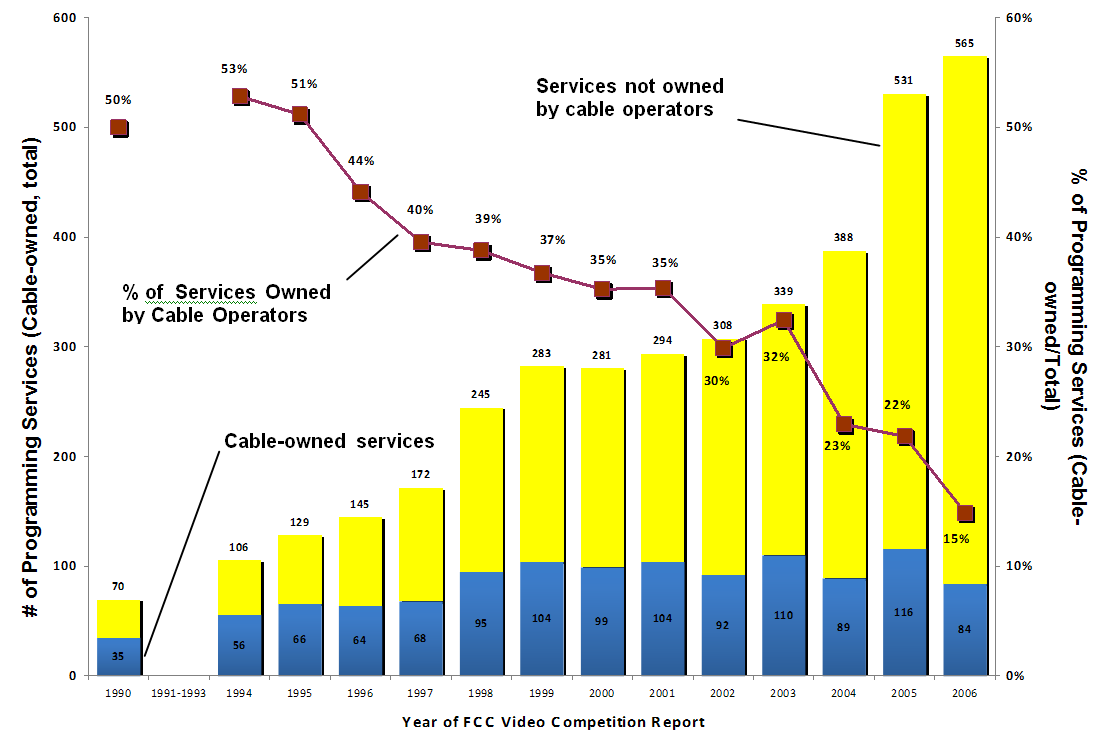

Second, over the same period there has been a dramatic increase both in the number of cable networks and in the programming available to subscribers.

Our chart shows the explosion in the number of programmers (though not the total amount of programming), as well as the falling rate of affiliation between cable operators and programmers, which was among the prime factors motivating Congress when it authorized a cable cap in the 1992 Cable Act:

Continue reading →

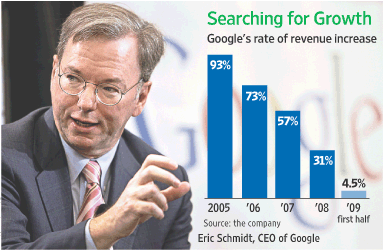

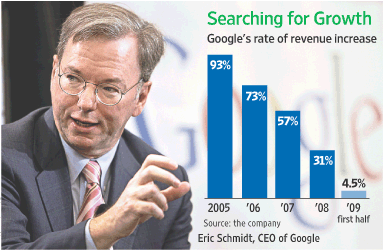

The Google juggernaut’s revenue growth has slowed steadily in the last five years, causing the Wall Street Journal to caution investors about buying Google stock. While much of the slow-down in Google’s revenue may be attributed to the recession, the WSJ cautions that:

The Google juggernaut’s revenue growth has slowed steadily in the last five years, causing the Wall Street Journal to caution investors about buying Google stock. While much of the slow-down in Google’s revenue may be attributed to the recession, the WSJ cautions that:

- Microsoft is offering stiffer competition in search, which will only intensify once antitrust regulators approve its partnership with Yahoo! and the two companies actually implement their partnership (which could take another year);

- YouTube’s promise as an ad platform remains uncertain;

- Google lags behind Apple and Research in Motion in developing mobile phone operating systems, with Android still unproven;

- It remains unclear how successful the company will be in expanding beyond its existing lead in small text ads into the potentially lucrative realm of banner ads.

Somehow I doubt Google’s fall to Earth will do much to allay the concerns of those who see Google as the kind of evil monopolist Microsoft was made out to be in the 90s.

As the Journal concludes, “It would be foolish to predict that Google won’t have another business success, of course… Google may itself discover the next Google-like business.” As long as someone’s out there working to turn today’s idle fantasies into tomorrow’s multi-billion dollar businesses, consumers win—whoever that bold innovator might be.

Ahoy, TLFers! Looking for a way to do your part for the Cyber-Libertarian Resistance?

We’ve recently upgraded the site with a new look developed by our own Jerry Brito (preserving PJ Doland’s iconic art work) based on the Thesis Theme for WordPress. We now need help customizing Thesis to improve the functionality of the site—like allowing users to access lists of content sorted by category, author or tag. If you think you might be able to help, please drop me a line at bszoka [at] pff [dot] org. We’d be very grateful for your help!

Make sure to read George Ou’s two recent articles over at the Digital Society blog setting the record straight about broadband usage caps: “Putting American Bandwidth Caps into Context” and “We Need to be Reasonable about Broadband Usage Caps.” George is one sharp cookie. I particularly like the way he takes apart Free Press for their hypocrisy on this issue, something I have commented on here before after George brought it to my attention. See:

… and here’s some older material on the issue…

In a post earlier this week, I discussed Randy Cohen’s “guideline” for anonymous blogging. Specifically, Cohen argued in a recent New York Times piece that, “The effects of anonymous posting have become so baleful that it should be forsworn unless there is a reasonable fear of retribution. By posting openly, we support the conditions in which honest conversation can flourish.” While sympathetic to that guideline, I noted I agreed with it as an ethical principle, not a legal matter. In others words, what might make sense as a “best practice” for the Internet and its users would not make sense as a regulatory standard. I prefer using social norms and public pressure to drive these standards, not regulation that could have an unintended chilling effect on beneficial forms of anonymous online speech.

In a post earlier this week, I discussed Randy Cohen’s “guideline” for anonymous blogging. Specifically, Cohen argued in a recent New York Times piece that, “The effects of anonymous posting have become so baleful that it should be forsworn unless there is a reasonable fear of retribution. By posting openly, we support the conditions in which honest conversation can flourish.” While sympathetic to that guideline, I noted I agreed with it as an ethical principle, not a legal matter. In others words, what might make sense as a “best practice” for the Internet and its users would not make sense as a regulatory standard. I prefer using social norms and public pressure to drive these standards, not regulation that could have an unintended chilling effect on beneficial forms of anonymous online speech.

Dan Gillmor of the Center for Citizen Media of the Harvard Berkman Center has a new column up at the UK Guardian in which he takes a slightly different cut at a new standard or social norm for dealing with some of the more caustic anonymous speech out there:

One of the norms we’d be wise to establish is this: People who don’t stand behind their words deserve, in almost every case, no respect for what they say. In many cases, anonymity is a hiding place that harbours cowardice, not honour. The more we can encourage people to use their real names, the better. But if we try to force this, we’ll create more trouble than we fix. But we don’t want, in the end, to turn everything over to the lawyers. The rest of us — the audience, if you will — need to establish some new norms as well.

Specifically, Gillmor argues that, ” We need to readjust our internal BS meters in a media-saturated age,” because “We are far too prone to accepting what we see and hear.” I think Gillmor has too little faith in most digital denizens; most of us take anonymous comments with a grain of salt and assume that the ugliest of those comments are often untrue. And that’s generally the “principle” he recommends each of us adopt going forward: Continue reading →

If only our would-be “Net Nannies” in Congress, the FCC, FTC, state capitols and, of course, Brussels were more like the Park Service! The WSJ reports on “Why there are so few guardrails at the Grand Canyon:”

Sunday a crowd gathered in Acadia National Park, on Mount Desert Island along the Maine coast, to watch the surf, roaring with energy from an offshore hurricane, smash against the shore. A towering wave crashed over some onlookers, dragging half a dozen into the ocean. A 7-year-old girl drowned. Soon it was asked why officials had let the crowd get so near waters so dangerous. “The Park Service’s goal is to get people out into the park,” Acadia Chief Ranger Stuart West told Maine Public Broadcasting. “And we don’t want to take that opportunity away from the public.”

It’s a measure of how coddled we’ve become that Mr. West’s simple and reasonable statement seems almost shocking. But the Park Service, with its emphasis on protecting the lands in its care, has developed a refreshingly laissez-faire attitude toward protecting visitors….

It seems that those who frequent the outdoors have an aversion to nanny-statism, which allows the Park Service to take a grown-up attitude toward its visitors: “Their safety is their responsibility,” says Ron Terry, Zion’s public information officer. “We couldn’t possibly put railings up everywhere. It wouldn’t be feasible, nor would we want to.”

Amen! If only we took the same approach to the online environment: educate users about the risks (real or subjective) to their privacy, safety or delicate sensibilities and empower them to the maximum extent possible to make decisions for themselves—or for parents to decide which “perilous canyon trails” to let their kids go down. The wonderful, unique thing about the online environment is that each user’s experience can be customized: Technological filters tools allow parents to create “guardrails” just for their kids (e.g., blacklists of sites inappropriate for kids), without needing to have a guardrail installed for all users (e.g., COPA).

The parallels continue when one considers the human tendency to mis-perceive risks, which creates “technopanics” in Internet policy just as it creates panics about the various health risks of the great outdoors: Continue reading →

According to a report by CNET’s Declan McCullagh, a draft bill in the U.S. Senate would grant President Obama “cybersecurity emergency powers” to disconnect and even seize control of private sector computers on the Internet.

Back in May, when Obama proposed a “cybersecurity czar with a broad mandate” and the administration issued a report outlining potential vulnerabilities in the government’s information security policies, I cautioned about the constant temptation by politicians in both parties to expand government authority over “critical’ private networks.” From American telecommunications to the power grid, virtually anything networked to some other computer would potentially be fair game for Obama to exercise “emergency powers.”

Policy makers should be suspicious of proposals to collectivize and centralize cybersecurity risk management, especially in frontier industries like information technology. When government asserts authority over security technologies, it hinders the evolution of more robust information security practices and creates barriers to non-political solutions—both mundane and catastrophic. The result is that we become less secure, not more secure.

Instead, the Obama Administration should limit its focus to securing government networks and keeping government agencies on the cutting edge of communications technology. As today’s news illustrates, the dangers created by such a broad mandate may come to pass.

Texting while driving is generally a bad idea, since it involves taking one’s hands off the wheel and eyes off the road. While not wearing your seatbelt in a car or a helmet on a motorcycle probably only risks your own life, there’s a good argument to be made that distracted drivers put the lives of others at risk. The WSJ reports that 17 states have banned texting while driving outright. But is such regulation really the best way to address the problem?

Technological Empowerment. The WSJ highlights innovative technological solutions that:

- Block calls and texts while the user is driving; OR

- Let drivers “speak” their texts using voice-to-text technology.

Those who consider even hands-free cell phone use unsafe will probably insist on the more draconian blocking solution—and want government to mandate it! Such mandates would indeed probably be more effective than relying on the police write tickets to drivers they see texting while driving (especially since such offenses, like calling while driving, usually require some other, more serious offense before an officer can pull over a driver). But do we really need the government telling us when we can use a technology that really might be essential in certain circumstances, or totally safe in others (say, when we’re behind the wheel but stopped at a long light or in a traffic jam)?

The fascinating thing is that these solutions need not be mandated by government: At least some users will actually pay for them! Why? Because, sometimes we’re better off by being able to “bind” our future selves—just as Ulysses asked his crew to tie him to his ship’s mast so he could enjoy the Siren’s enchanting song without giving in to their spell. Similarly, these texting-blocking technologies empower users in three senses:

- Some users know they shouldn’t text while driving but—like smokers and people who casually pick their noses—just can’t stop, so they want external discipline;

- Others just want the monthly discount on their car insurance; and

- Parents want to make sure they can discipline their children, who have a hard time resisting the impulse to pick up the phone.

Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.