As Berin mentioned last week, we have a new paper out on proposals to expand the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) of 1998. We generically refer to those COPPA-expansion efforts as “COPPA 2.0.” Hence, the title of our paper: “COPPA 2.0: The New Battle over Privacy, Age Verification, Online Safety & Free Speech.” To recap what Berin already noted, in the name of improving online child safety, some legislators and state attorneys general (AGs) are advocating the expansion of COPPA’s “verifiable parental consent” model of age verification before certain sites or services may collect, or enable the sharing of, personal information for children.

Unlike “COPPA 1.0,” however, which only applied to children under the age of 13, “COPPA 2.0” would apply to all minors up to age 17. Moreover, the range of sites covered by the new law would generally be expanded to include just about any site or service with social networking functionality.

Since Berin has already summarized our general concerns with efforts to expand COPPA’s “verifiable parental consent” online age verification system to cover more online users and sites, I thought I would focus here on what I believe will be the most controversial (and important) part of our paper — our discussion about how COPPA 2.0 affects the speech rights of both adults and adolescents.

Continue reading →

Says Epic Games founder and CEO Tim Sweeney. I wonder what the FTC will think about this prospect in the report Congress asked them to send this year about video games. I think it’s safe to assume that the thought of life-like sex and violence will create a true technopanic.

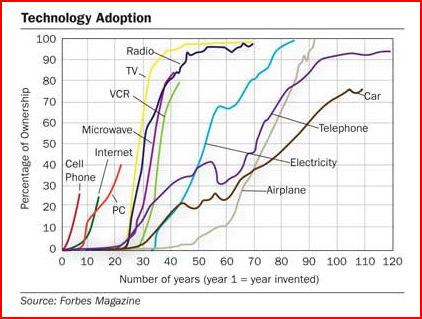

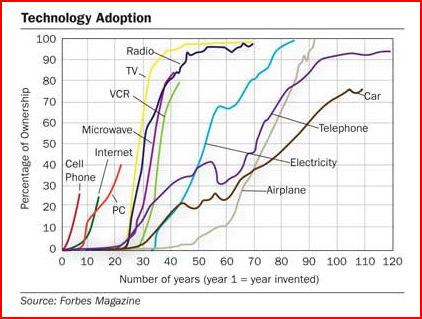

Via Kevin Kelly I see that at some point Forbes magazine produced this chart measuring technology diffusion rates for various media and communications technologies since their year of inception.

I found this of great interest because, since the mid-90s, I have been putting together various charts and tables illustrating technological diffusion [most recently I did this in my “Media Metrics” report] and this particular chart is quite challenging since you are forced to pick a “Year 1” date to begin each of the “S curves.” For example, what is “Year 1” for electricity or telephony on one hand, or the PC or the Internet on the other? That’s not always easy to determine since it is unclear when certain technologies were “born.”

Regardless, no matter how you cut it, the more modern and the less regulated the technologies, the quicker they get to market. Here’s a couple of my recent charts illustrating that fact. The first shows how long it took before various technologies reached 50% household penetration. The second illustrates the extent of household diffusion over time.

However, as Kevin Kelly notes, we usually never see any technology hit 100% household penetration (although the boob tube got close!):

Continue reading →

Recall a couple of years ago when I lauded Google – and also picked on them – for making customer data “more anonymous”?

“‘Anonymous’ is correctly regarded as an absolute condition,” I wrote. “Like pregnancy, anonymity is either there or it’s not. Modifying the word with a relative adjective like ‘more’ is a curious use of language.”

The challenge of these concepts – “anonymized” or “de-identified” data – is still around, and it’s still a difficult one.

Here’s a sophisticated take on the question:

Information is increasingly difficult to classify as “identified” or “de-identified,” particularly as it is copied, exchanged, or recombined with other information. With rapidly evolving technologies and databases, it is more appropriate to describe a spectrum of “identifiability,” rather than a binary classification of information as identifiable or not. The question could then become not whether deidentified information might be made re-identifiable, but rather which entities would be able to re-identify the information, how much effort they would have to expend, and what limits are placed on their doing so.

And here’s an advocacy group apparently lacking that sophistication. They treat information as flatly “de-identified” in a legal filing about a New Hampshire law that bans the sale of prescription drug data for marketing purposes:

[T]he Prescription Information Law does not implicate patient privacy. While it purports to protect privacy interests, the statute regulates patient de-identified information.

Here’s the thing: Both quotes were issued by the Center for Democracy and Technology. Continue reading →

I’m reading a couple of interesting books right now [see my Shelfari list here] including Guarding Life’s Dark Secrets: Legal and Social Controls over Reputation, Propriety, and Privacy by Lawrence Friedman of the Stanford School of Law. The book examines the legal and social norms governing privacy, reputation, sex, and morals over the past two centuries. It’s worth putting on your reading list. [Here’s a detailed review by Neil Richards.] I might pen a full review later but for now I thought I would just snip this passage from the concluding chapter:

In an important sense, privacy is a modern invention. Medieval people had no concept of privacy. They also had no actual privacy. Nobody was ever alone. No ordinary person had private space. Houses were tiny and crowded. Everyone was embedded in a face-to-face community. Privacy, as idea and reality, is the creation of a modern bourgeois society. Above all, it is a creation of the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century it became even more of a reality. [p. 258]

In a time when amorphous “rights” to privacy seem to be multiplying like wildflowers, this is an important insight from Friedman. In my opinion, many of the creative privacy theories being concocted today are often based on false nostalgia about some forgotten time in the past when we supposedly all had our own little quiet spaces that were completely free from privacy intrusions. But as Friedman makes clear, this is largely a myth. It’s not to say that there aren’t legitimate issues out there today. But it’s important that we place modern privacy issues in a larger historical context and understand how many of today’s concerns pale in comparison to the problems of the past.

[Note: If you’re interested in this topic, you’ll also want to read Daniel Solove’s The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet. Also, here’s Jim Harper’s review of it.]

Adam Thierer & I have just released a detailed examination (PDF) of brewing efforts to expand the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 to cover adolescents and potentially all social networking sites—an approach we call “COPPA 2.0.”

As Adam explained on Larry Magid’s CNET podcast, COPPA mandates certain online privacy protections for children under 13, most importantly that websites obtain the “verifiable consent” of a child’s parent before collecting personal information about that child or giving that child access to interactive functionality that might allow the child to share their personal information with others. The law was intended primarily to “enhance parental involvement in a child’s online activities” as a means of protecting the online privacy and safety of children.

Yet advocates of expanding COPPA—or “COPPA 2.0″—see COPPA’s verifiable parental consent framework as a means for imposing broad regulatory mandates in the name of online child safety and concerns about social networking, cyber-harassment, etc. Two COPPA 2.0 bills are currently pending in New Jersey and Illinois. The accelerated review of COPPA to be conducted by the FTC next year (five years ahead of schedule) is likely to bring to Washington serious talk of expanding COPPA—even though Congress clearly rejected covering adolescents age 13-16 when COPPA was first proposed back in 1998.

We’ll discuss some of the key points of our paper in a series of blog posts, but here are the top nine reasons for rejecting COPPA 2.0, in that such an approach would:

- Burden the free speech rights of adults by imposing age verification mandates on many sites used by adults, thus restricting anonymous speech and essentially converging—in terms of practical consequences—with the unconstitutional Children’s Online Protection Act (COPA), another 1998 law sometimes confused with COPPA;

- Burden the free speech rights of adolescents to speak freely on—or gather information from—legal and socially beneficial websites;

- Hamper routine and socially beneficial communication between adolescents and adults;

- Reduce, rather than enhance, the privacy of adolescents, parents and other adults because of the massive volume of personal information that would have to be collected about users for authentication purposes (likely including credit card data);

Continue reading →

Lee Gomes writes on Fobes.com with a clear-eyed reminder that privacy regulation has been costly, yet failed to deliver. Lovers of government intervention will, of course, take this as an argument to double-down.

craigslist has filed a complaint against South Carolina Attorney General Henry McMaster, seeking to enjoin him from prosecuting the site for displaying the solicitations to prostitution that sometimes appear there. The complaint cites section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, the First Amendment, and a few other laws that craigslist believes protect it from liability.

The complaint makes a pretty good case that craigslist has taken reasonable steps, working with law enforcement, to keep prostitution off the site. With that it has done its part. If prosecutors want to go after prostitution, they can use craigslist to do so. They should not attack the messenger if consenting adults are trying to exchange money for sexual services in their local areas.

California has asked the Supreme Court to review a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decision holding that a California video game statute was unconstitutional. [Game Politics.com has complete coverage, and there’s more over at Ars and USA Today’s Game Hunters blog.]

California has asked the Supreme Court to review a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals decision holding that a California video game statute was unconstitutional. [Game Politics.com has complete coverage, and there’s more over at Ars and USA Today’s Game Hunters blog.]

Brief background: In late February, the Ninth Circuit upheld an August 2007 ruling by a California district court decision in the case of Video Software Dealers Association v. Schwarzenegger [decision here], which struck down a California law, passed in October 2005 (A.B.1179), which would have blocked the sale of “violent” video games to those under 18 and required labels on all games. Offending retailers could have been fined for failure to comply with the law. After being challenged by the Video Software Dealers Association and the Entertainment Software Association and, the district court blocked the law arguing that it violated both the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the federal Constitution.

California’s decision to appeal the law up to the Supreme Court [petition is here] sets up a potential historic First Amendment decision (if they Court agrees to take the case, that is). California is asking the Court to consider two questions:

1. Does the First Amendment bar a state from restricting the sale of violent video games to minors?

2. If the First Amendment applies to violent video games that are sold to minors, and the standard of review is strict scrutiny, under Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. v. F.C.C., 512 U.S. 622, 666 (1994), is the state required to demonstrate a direct causal link between violent video games and physical and psychological harm to minors before the state can prohibit the sale of the games to minors?

California is essentially asking the Supreme Court to engage in a constitutional revolution and upset a century’s worth of First Amendment jurisprudence.

Continue reading →

. . . you’d think that you would follow the “Speeches” link from the home page on Whitehouse.gov. If you do, today you see just four speeches.

I went looking for the text of his national security speech at the National Archives today. The New York Times has it but Whitehouse.gov doesn’t? What’s going on here?

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.