President-elect Barack Obama will soon be naming Cass Sunstein, an old friend of his from their University of Chicago Law School days together, the new head the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA). OIRA oversees regulation throughout the U.S. government. Basically, Sunstein’s position is the equivalent of the federal regulatory czar.

President-elect Barack Obama will soon be naming Cass Sunstein, an old friend of his from their University of Chicago Law School days together, the new head the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA). OIRA oversees regulation throughout the U.S. government. Basically, Sunstein’s position is the equivalent of the federal regulatory czar.

Sunstein certainly possess excellent qualifications for the job. During his time at the University of Chicago and Harvard Law School, Sunstein has established himself as a leading liberal thinker in the field of law and economics. And, as I have joked in writing about him before, he is so insanely prolific that it seems every time I finish reading one of his new books a new title by him lands on my desk. I am quite convinced that both he and Richard Posner are actually cyborgs. I just don’t understand how two humans can compose words so rapidly!

Anyway, Professor Sunstein’s new position as head of OIRA gives him the ability influence federal regulatory decisions in both a procedural and substantive way. In terms of substance, it gives him an important platform to subtly “nudge” the regulatory philosophy and direction of the Obama Administration on many matters, including Internet policy. So, what has Professor Sunstein had to say about Internet policy in his recent work? Sunstein has developed his thinking about these issues primarily in his two recent books: Republic.com (2000) and Infotopia: How Many Minds Produce Knowledge (2006). But he’s also had a few relevant things to say about Internet issues in his recent book with Richard Thaler, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness (2008).

There are 3 Internet policy-related things from his work that I’d like to focus on here because I find them all quite troubling. Continue reading →

Regarding Stanford Law Professor Larry Lessig’s proposal to abolish the Federal Communications Commission: Adam covered the main points here and I’d like to add a couple minor points.

The idea of abolishing the FCC used to be a right-wing fantasy. But now Silicon Valley-booster Lessig is on board.

With so much in its reach, the FCC has become the target of enormous campaigns for influence. Its commissioners are meant to be “expert” and “independent,” but they’ve never really been expert, and are now openly embracing the political role they play. Commissioners issue press releases touting their own personal policies. And lobbyists spend years getting close to members of this junior varsity Congress. Think about the storm around former FCC Chairman Michael Powell’s decision to relax media ownership rules, giving a green light to the concentration of newspapers and television stations into fewer and fewer hands. This is policy by committee, influenced by money and power, and with no one, not even the President, responsible for its failures.

Relaxing media ownership rules was and is a good idea, but aside from that Lessig is absolutely correct. The FCC has a history of inhibiting innovation, protecting favored clients and persecuting politically-unpopular industry segments who stand up for their legitimate rights. But politics are nasty, so none of this should be surprising.

Lessig is also correct that

The solution here is not tinkering. You can’t fix DNA. You have to bury it. President Obama should get Congress to shut down the FCC and similar vestigial regulators, which put stability and special interests above the public good.

Continue reading →

I’m re-reading Tim Lee’s excellent and very long paper on network neutrality, “The Durable Internet.” It’s excellent partly because it’s such a long read—it’s exhaustive in addressing all the issues surrounding the neutrality debate.

I’m re-reading Tim Lee’s excellent and very long paper on network neutrality, “The Durable Internet.” It’s excellent partly because it’s such a long read—it’s exhaustive in addressing all the issues surrounding the neutrality debate.

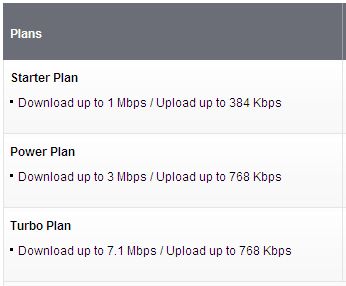

With all the great writing—like Tim’s paper—available on the topic, I can’t understand why so many people who write about technology are still confused on the issue of neutrality. If neutrality is to be understood as some form of the end-to-end principle with a bit of marketing-speak slathered on top, then how can people continue to conflate it with something as basic as differing levels of service from ISPs?

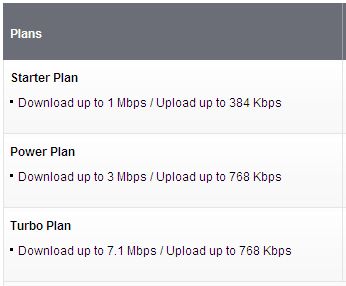

The latest example is Dan Costa writing in the last print edition of PC Magazine. While Costa’s basic point is correct—he says it’s fair to charge people who use more bandwidth more money for their Internet connection—he seems to think it might be non-neutral. Sure, it’s non-uniform pricing, but it’s not a violation of net neutrality.

I agree with Costa that it makes sense to charge consumers for what they consume. To argue this is impermissible would be to argue against the basic principle of fairness. As Costa says in his column, “Can’t we all agree that my mom and I shouldn’t be paying the same price for broadband?”

The neutrality debate has become a confused mishmash of legitimate concerns over network management practices and the cries of folks who think broadband should be free, or the same low low price for everyone. I think it’d be great if everyone writing on the matter read Tim’s paper, read the other side of the issue over at places like Free Press, and started speaking sense on the topic.

For geek news gluttons, there’s more to say about Costa’s column, like the TOS of Sprint’s XOHM service, but I’ll leave that to the for those of you who don’t mind long windedness. (Like those of you who actually read Tim’s treatise on neutrality.) I talk more about Costa’s column at OpenMarket.org.

Hey, you’d make mistakes too if you were up at 5:00 a.m. sending emails.

Naturally, now that government plans to intervene in the economy with a massive stimulus package, everyone wants their “fair” share. Robert D. Atkinson, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, is arguing for digitized health records, a smart power grid and faster broadband connections:

While creating jobs by upgrading the nation’s physical infrastructure may help in the short term, Mr. Atkinson says, “there’s another category of stimulus you could call innovation or digital stimulus — ‘stimovation,’ as a colleague has referred to it.” Although many economists believe that a stimulus package must be timely, targeted and temporary, Mr. Atkinson’s organization argues that a fourth adjective — transformative — may be the most important. Transformative stimulus investments, he said, lead to economic growth that wouldn’t be there otherwise.

A new report by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation [to be released Wednesday] presents the case for investing $30 billion in the nation’s digital infrastructure, including health information technology, broadband Internet access and the so-called smart grid, an effort to infuse detailed digital intelligence into the electricity distribution grid.

And a Silicon Valley petition calls for a tax credit for companies that spend more than 80 percent of what they had been spending annually on information technology like computers and software.

Usually when politicians hand out targeted tax breaks or grants there are strings attached.

Free Press is already proposing that the Internet services receiving subsidies “must be an open, freely competitive platform for ideas and commerce.” There is a possibility no one would accept the subsidies to build the network Free Press envisions. Continue reading →

Continuing the “Cutting the (Video) Cord” series started by my PFF colleague Adam Thierer: The WSJ had two great pieces yesterday about the increasing competitive relevance of television distributed by Internet—a trend that was at the heart of an amicus brief PFF recently filed in support of C omcast’s challenge of the FCC’s 30% cap on cable ownership. The first WSJ piece declares that:

After more than a decade of disappointment, the goal of marrying television and the Internet seems finally to be picking up steam. A key factor in the push are new TV sets that have networking connections built directly into them, requiring no additional set-top boxes for getting online. Meanwhile, many consumers are finding more attractive entertainment and information choices on the Internet — and have already set up data networks for their PCs and laptops that can also help move that content to their TV sets.

The easier it is for consumers to receive traditional television programming (in addition to other kinds of video content) distributed over the Internet on their television, the less “gatekeeper” or “bottleneck” power cable distributors have over programming. So the Netflix-capable and Yahoo-widget-capable televisions described by the WSJ piece go a long way to increasing the substitutability of what we call Internet Video Programming Distributors (IVPDs) for Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (MVPDs), such as cable, satellite television and fiber services offered by telcos such as Verizon’s FiOS.

and Yahoo-widget-capable televisions described by the WSJ piece go a long way to increasing the substitutability of what we call Internet Video Programming Distributors (IVPDs) for Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (MVPDs), such as cable, satellite television and fiber services offered by telcos such as Verizon’s FiOS.

While such televisions are only expected to reach 14% of all TV sales by 2012, one must remember that a growing number of set-top boxes (e.g., the Roku Digitial Video Player, game consoles like the Microsoft XBox 360 and Sony PlayStation 3, and TiVo DVRs) allow users to users to receive IVPD programming on their existing televisions.

As we argued in our amicus brief, the immense competitive importance of IVPDs lies not in the potential for some users to “cut the cord” to cable and other MVPDs (though that will surely happen), but in the immediate impact IVPDs have as an alternative distribution channel for programmers. In the pending D.C. Circuit case, we argue that both the FCC’s 30% cap, issued in December 2007, and the underlying portions of the 1992 Cable Act authorizing such a cap should be struck down as unconstitutional because the ready availability of IVPDs as an alternative distribution channel means that cable no longer has the “special characteristic” of gatekeeper/bottleneck power that would justify imposing such a unique burden on the audience size of cable operators. (Of course, Direct Broadcast Satellite and Telco Fiber are also eating away at cable’s share of the MVPD marketplace.)

The second WSJ piece, an op/ed, illustrates beautifully how cable operators are already losing “market power” (or at least negotiating leverage) in a very tangible way: they’re having to pay more for programming. Specifically, the Journal describes how Viacom plaid chicken with Time Warner—and won. Continue reading →

Microsoft’s share of the browser market across all versions of Internet Explorer has dropped, by one estimate, dropped from 78.58% in December 2007 to 68.15% in December 2008 (or by just under 8% in another estimate).

[IE’s] share dropped from 69.77% in November to 68.15% in December. [During the same period,] Firefox gained more than half a point and ended up at 21.34%, Safari approaches the [10%] hurdle with 7.93% and Chrome came in at 1.04%, the first time Google was able to cross the 1% mark.

This is particularly interesting:

Since IE6 is used primarily within corporations, its market share is much higher during the week than it is on weekends. As a result, all other browsers gain on weekends and especially during a holiday. Because of that circumstance, Net Applications noted that the December numbers should be taken with a grain of salt. However, it is worth the note that IE6 achieved … market share numbers of about 28% during the week and about 21% on weekends in early 2008. In December, these numbers were down to about 20% during the week and 15% on weekends.

So, Microsoft still has an established base among corporate users, where IT administrators generally prevent employees from installing new applications (including browsers) and the sysadmins often don’t roll out alternative browsers across a corporate network for any one of several possible reasons, including:

- They just don’t want to bother having to install, regularly upgrade and support another piece of software;

- They may overestimate the security vulnerability of such alternative browsers compared to Internet Explorer;

- The crustier sysadmins may not realize that today’s browsers are not only free for individual users, but also for corporate users–unlike the old Netscape Navigator; and

- Corporate intranets may be designed for IE, in which case rolling out an alternative browser might cause confusion among less tech-savvy employees.

Microsoft may still have an advantage that could be considered “unfair,” but so what? Continue reading →

The FCC’s much-maligned proposal to create a free, filtered wireless broadband network seemed all but dead earlier this week after FCC Chairman Kevin Martin stated in an interview with Broadcast & Cable that the proposal’s chances of surviving a full FCC vote were “dim.”

The FCC’s much-maligned proposal to create a free, filtered wireless broadband network seemed all but dead earlier this week after FCC Chairman Kevin Martin stated in an interview with Broadcast & Cable that the proposal’s chances of surviving a full FCC vote were “dim.”

Now, Ars reports that Kevin Martin has changed his mind about the filtering requirements, caving in to pressure from an array of interest groups to drop the smut-free provisions from the plan. These “family-friendly” rules, which would have mandated that the network filter any content deemed unsuitable for a five-year-old, ended up acting as a lightning rod for critics across the ideological spectrum, and raised serious First Amendment concerns (as Adam and Berin have argued on several occasions).

Even with the smut-free rules having been removed, the proposal remains a very bad idea. Setting aside 25 mhz of the airwaves—a $2 billion chunk of spectrum—to blanket the nation with free wireless broadband (as defined by the FCC) would mean less spectrum available for more robust services. At a time when wireless firms are experimenting with a number of strategies for monetizing the airwaves, allowing a single firm’s business model—especially one that many experts have suggested is simply not viable—to reign over other, more effective models would hurt consumers who yearn for more than basic broadband service.

The case for setting spectrum aside for free wireless broadband is predicated on the myth that there exists an elusive “public interest” that the marketplace is unable to maximize. We’ve heard the same line many times before. It goes something like this: The forces of competition that we rely upon to allocate finite resources in nearly every other sector of the economy are incapable of fulfilling consumer needs when it comes to broadband. Washington DC intellectuals have figured out that the public really wants a free nationwide wireless network—yet this amazing concept has been blocked by evil incumbents that are bent on denying consumers the services they most desire.

Continue reading →

I’m in the mood for making bold predictions, so I predict (with fingers crossed) that we won’t see neutrality regulation passed in 2009. I want to say right away that this is more of a hope than a assessment of the regulation’s political chances, but it’s a hope worth sharing.

I’m in the mood for making bold predictions, so I predict (with fingers crossed) that we won’t see neutrality regulation passed in 2009. I want to say right away that this is more of a hope than a assessment of the regulation’s political chances, but it’s a hope worth sharing.

Over at OpenMarket.org, the blog of the Competitive Enterprise Institute, I have spelled out my reasons for thinking that neutrality regulation won’t pass and why I think market-enforced neutrality would be a much more robust system for keeping the Net thriving.

President-elect Barack Obama will soon be naming Cass Sunstein, an old friend of his from their University of Chicago Law School days together, the new head the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA). OIRA oversees regulation throughout the U.S. government. Basically, Sunstein’s position is the equivalent of the federal regulatory czar.

President-elect Barack Obama will soon be naming Cass Sunstein, an old friend of his from their University of Chicago Law School days together, the new head the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA). OIRA oversees regulation throughout the U.S. government. Basically, Sunstein’s position is the equivalent of the federal regulatory czar.

and Yahoo-widget-capable televisions described by the WSJ piece go a long way to increasing the substitutability of what we call Internet Video Programming Distributors (IVPDs) for Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (MVPDs), such as cable, satellite television and fiber services offered by telcos such as Verizon’s FiOS.

and Yahoo-widget-capable televisions described by the WSJ piece go a long way to increasing the substitutability of what we call Internet Video Programming Distributors (IVPDs) for Multichannel Video Programming Distributors (MVPDs), such as cable, satellite television and fiber services offered by telcos such as Verizon’s FiOS.  The FCC’s

The FCC’s  I’m in the mood for making bold predictions, so I predict (with fingers crossed) that we won’t see neutrality regulation passed in 2009. I want to say right away that this is more of a hope than a assessment of the regulation’s political chances, but it’s a hope worth sharing.

I’m in the mood for making bold predictions, so I predict (with fingers crossed) that we won’t see neutrality regulation passed in 2009. I want to say right away that this is more of a hope than a assessment of the regulation’s political chances, but it’s a hope worth sharing. The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.