My favorite thing about Ars Technica (aside from the fact that I get to write for them) is their in-depth features on technical issues. Out today is the best discussion I’ve seen of transit and peering for the lay reader. One key section:

I once heard the following anecdote at a RIPE meeting.

Allegedly, a big American software company was refused peering by one of the incumbent telco networks in the north of Europe. The American firm reacted by finding the most expensive transit route for that telco and then routing its own traffic to Europe over that link. Within a couple of months, the European CFO was asking why the company was paying out so much for transit. Soon afterward, there was a peering arrangement between the two networks…

Tier 1 networks are those networks that don’t pay any other network for transit yet still can reach all networks connected to the internet. There are about seven such networks in the world. Being a Tier 1 is considered very “cool,” but it is an unenviable position. A Tier 1 is constantly faced with customers trying to bypass it, and this is a threat to its business. On top of the threat from customers, a Tier 1 also faces the danger of being de-peered by other Tier 1s. This de-peering happens when one Tier 1 network thinks that the other Tier 1 is not sufficiently important to be considered an equal. The bigger Tier 1 will then try to get a transit deal or paid peering deal with the smaller Tier 1, and if the smaller one accepts, then it is acknowledging that it is not really a Tier 1. But if the smaller Tier 1 calls the bigger Tier 1’s bluff and actually does get de-peered, some of the customers of either network can’t reach each other.

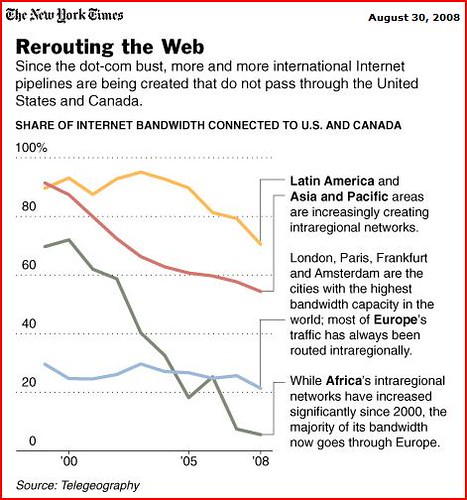

When I first learned about the Internet’s basic peering model, it seemed like there was a real danger of a natural monopoly developing if too many tier 1 providers merge or collude. But what this misses is that larger networks are facing a constant threat of having their customers bypass them and peer directly with other customers. As a result, even if there were only one tier 1 provider, that provider wouldn’t have that much monopoly power, because any time it raised its prices it would see its largest customers start building out infrastructure to bypass its network.

In effect, the BGP protocol that controls the interactions of the various network creates a highly liquid market for interconnection. Because a network has the technical ability to change its local topology in a matter of hours, it’s always in a reasonably strong bargaining position, even when dealing with a larger network.

Things are trickier in the “last mile” broadband market, but at least if we’re talking about the Internet backbone, this is a fiercely competitive market and seems likely to remain that way for the foreseeable future.

Google is entering the browser wars today (if any such war still exists) with the launch of

Google is entering the browser wars today (if any such war still exists) with the launch of

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.