In the previous installment of my ongoing “Media Metrics” series, I highlighted the radical metamorphosis taking place in the market for audible information and entertainment. I showed that this previously stable sector now finds itself in a state of seemingly constant upheaval, especially thanks to the blistering pace of technological change we are witnessing today.

In this sixth installment of the Media Metrics series, we will see how a similar transformation has taken place in the video marketplace over the past three decades. Again, using the analytical framework I presented in the first installment, we will see that today we have more choice, competition, and diversity in every part of the video value chain. [You might also be interested in reviewing the third installment in this series dealing with advertising competition and the fourth installment dealing with changing media fortunes.]

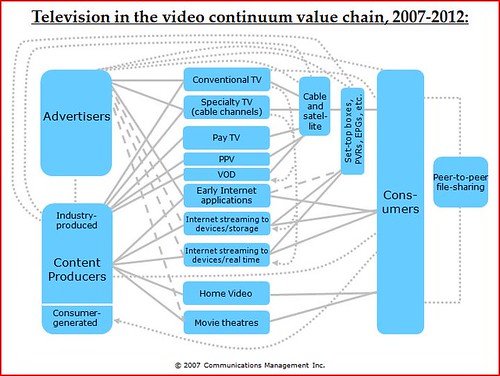

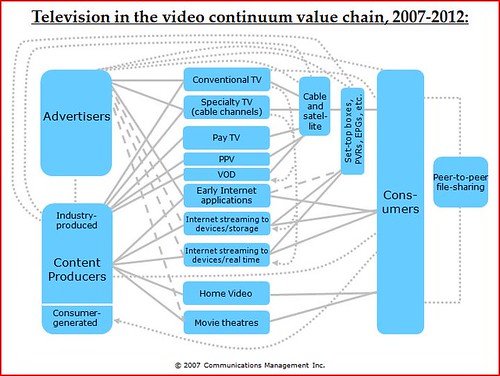

Kenneth Goldstein of Winnipeg, Canada-based Communications Management, Inc., has put together a set of enlightening television value chains that compares the state of the marketplace in 1975 to present.

Exhibit 1

Exhibit 2

Continue reading →

Larry Lessig is a gifted writer, and he does a good job of finding and telling stories that illustrate the points he’s trying to make. I found Free Culture extremely compelling for just this reason; he does a great job of illustrating a fairly subtle but pervasive problem by finding representative examples and weaving together a narrative about a broader problem. He demonstrates that copyright law has become so pervasive that peoples’ freedom is restricted in a thousand subtle ways by its over-broad application.

He takes a similar approach in Code, but the effort falls flat for me. Here, too, he gives a bunch of examples in which “code is law”: the owners of technological systems are able to exert fine-grained control over their users’ online activities. But the systems he describes to illustrate this principle have something important in common: they are proprietary platforms whose users have chosen to use them voluntarily. He talks about virtual reality, MOOs and MUDs, AOL, and various web-based fora. He does a good job of explaining that the different rules of these virtual spaces—their “architecture”—has a profound impact on their character. The rules governing an online space interact in complex ways with their participants to produce a wide variety of online spaces with distinct characters.

Lessig seems to want to generalize from these individual communities to the “community” of the Internet as a whole. He wants to say that if code is law on individual online communications platforms, then code must be law on the Internet in general. But this doesn’t follow at all. The online fora that Lessig describes are very different from the Internet in general. The Internet is a neutral, impersonal platform that supports a huge variety of different applications and content. The Internet as a whole is not a community in any meaningful sense. So it doesn’t make sense to generalize from individual online communities, which are often specifically organized to facilitate control, to the Internet in general which was designed with the explicit goal of decentralizing control to the endpoints.

Also, the cohesiveness and relative ease of control one finds on the Internet occurs precisely because users tend to use any given online service voluntarily. Users face pressures to abide by the generally-accepted rules of the community, and users who feel a given community’s rules aren’t a good fit will generally switch to a new one rather than make trouble. In other words, code is law in individual Internet communities precisely because there exists a broader Internet in which code is not law. When an ISP tries to control its users’ online activities, users are likely to react very differently. As we’ve seen in the case of the Comcast kerfuffle, users do not react in a docile fashion to ISPs that attempt to control their online behavior. And at best, such efforts produce only limited and short-term control.

I’m re-reading Larry Lessig’s Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace. I last read it about four years ago, long enough that I’d forgotten a lot of the specific claims Lessig made. One of the things that I think has clearly not occurred is his prediction that we would develop a “general architecture of trust” that would “permit the authentication of a digital certificate that verifies facts about you—your identity, citizenship, sex, age, or the authority you hold.” Lessig thought that “online commerce will not fully develop until such an architecture is established,” and that way back in 1999, we could “see enough to be confident that it is already developing.”

Needless to say, this never happened, and it now looks unlikely that it ever will happen. The closest we came was with Passport, which was pretty much a flop. We have instead evolved a system in which people have dozens of lightweight online identities for the different websites they visit, many of which involve little more than setting a cookie on one’s browser. The kind of universal, monolithic ID system that would allow any website to quickly and transparently learn who you are seems much less likely today than it apparently seemed to Lessig in 1999.

Of course, this would have been obvious to Lessig if he’d had the chance to read Jim Harper’s Identity Crisis. Jim explained that the security of an identifier is a function not only of the sophistication of its security techniques, but also of the payoff for breaking it. A single, monolithic identifier is a bad idea because it becomes an irresistible target for the bad guys. It’s also insufficiently flexible: Security rules that are robust enough for online banking is going to be overkill for casual web surfing. What I want, instead, are a range of identifiers of varying level of security, tailored to the sensitivity of the systems to which they control access.

Online security isn’t much about technology at all. For example, the most important safeguard against online credit card fraud isn’t SSL. It’s the fact that someone trying to buy stuff with a stolen credit card has to give a delivery location, which can be used by the police to apprehend him. Our goal isn’t and shouldn’t be maximal security in every transaction. Rather, it’s to increase security until the costs of additional security on the margin cease to outweigh the resulting reductions in fraud. If the size of a transaction is reasonably low, and most people are honest, quite minimalist security precautions may be sufficient to safeguard it. That appears to be what’s happened so far, and Lessig’s prediction to the contrary is starting to look rather dated.

So I’ve finished reading the Frischmann paper. I think it makes some interesting theoretical observations about the importance of open access to certain infrastructure resources. But I think the network neutrality section of the paper is weakened by a lack of specificity about what’s at stake in the network neutrality debate. He appears to take for granted that the major ISPs are able and likely to transform the Internet into a proprietary network in the not-too-distant future. Indeed, he seems to regard this point as so self-evident that he frames it as a simple political choice between open and closed networks.

But I think it’s far from obvious that anyone has the power to transform the Internet into a closed network. I can count the number of serious reports of network neutrality violations on my fingers, and no ISP has even come within the ballpark of transforming its network into a proprietary network like AOL circa 1994. Larry Lessig raised the alarm about that threat a decade ago, yet if anything, things have gotten more, not less, open in the last decade. We have seen an explosion of mostly non-commercial, participatory Internet technologies like Wikipedia, Flickr, blogs, YouTube, RSS, XMPP, and so forth. We have seen major technology companies, especially Google, throw their weight behind the Intenet’s open architecture. I’m as happy as the next geek to criticize Comcast’s interference with BitTorrent, but that policy has neither been particularly successful in preventing BitTorrent use, nor emulated by other ISPs, nor a harbinger of the imminent AOL-ization of Comcast’s network.

Before we can talk about whether a proprietary Interent is desirable (personally, I think it isn’t), I think we have to first figure out what kind of changes are plausible. I have yet to see anyone tell a coherent, detailed story about what AT&T or Verizon could do to achieve the results that Lessig, Benkler, Wu, and Frischmann are so worried about. Frischmann, like most advocates of network neutrality regulation, seem to simply assume that ISPs have this power and move on to the question of whether it’s desirable. But in doing so, they’re likely to produce regulation that’s not only unnecessary, but quite possibly incoherent. If you don’t quite know what you’re trying to prevent, it’s awfully hard to know which regulations are necessary to prevent it.

I’ve been reading Brett Frischman’s “An Economic Theory of Infrastructure and Commons Management”, which develops a general theory of infrastructure management and then applies this theory to (among other things) the network neutrality debate. I’ll likely have more to say about it once I’ve finished digesting it, but I wanted to note one offhand comment that I found interesting. On page 924, Frischmann writs:

A list of familiar examples [of “infrastructure”] includes: (transportation systems such as highway systems, railways, airline systems, and ports, (2) communications systems, such as telephone networks and postal services; (3) governance systems such as court systems; and (4) basic public services and facilities, such as schools, sewers, and water systems.

Which of these things isn’t like the others? Let me first quote his definition of “infrastructure resources”:

(1) The resource may be consumed nonrivalrously;

(2) Social demand for the resource is driven primarily by downstream productive activity that requires the resource as an input; and

(3) The resource may be used as an input into a wide range of goods and services, including private goods, public goods, and nonmarket goods.

As far as I can see, schools don’t fit any of these criteria. While there are certainly some under-attended schools who could be called non-rivalrous in some sense, there is typically a trade-off between the number of students in a classroom and the quality of instruction. And I suppose you could say that in general, education is a pre-condition for higher future earnings, but if we interpret this definition that broadly, almost everything is “infrastructure.” People couldn’t be productive citizens without food, so does that make farmers, supermarkets, and restaurants “infrastructure?”

Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.