For all its wonders, technology is not something policymakers can sprinkle on deep-seated economic and social problems to make them go away. Electronic employment eligibility verification – the idea of automated immigration-background checks on all newly hired workers – illustrates this well.

A national EEV program would immerse America’s workers and businesses in Kafkaesque bureaucracy and erode the freedoms of the American citizen, even as it failed to stem illegal immigration.

Ultimately, there is no alternative but for Congress to repair the broken immigration system by aligning legal immigration with our nation’s economic demand for labor.

Read about it in my new paper, “Electronic Employment Eligibility Verification: Franz Kafka’s Solution to Illegal Immigration.”

A podcast on it can be found here.

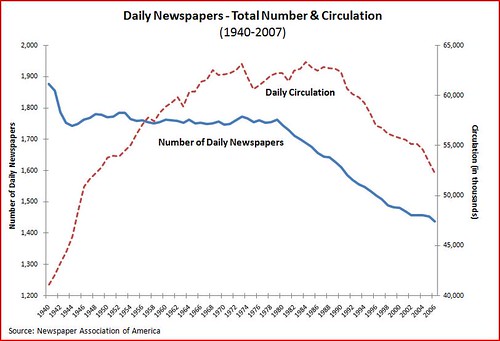

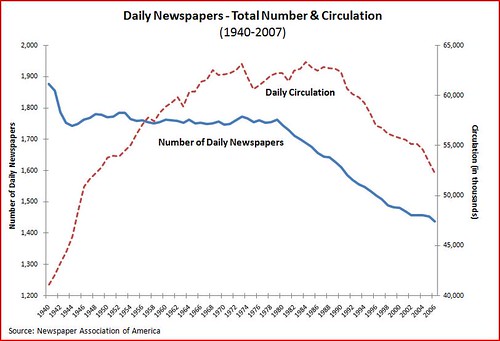

If we were to believe the rhetoric of some in Washington and various pro-regulatory groups like Free Press, you’d think we still lived in the 1800s and that a handful of newspaper barons like William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer still dominated our media landscape. Just today, in fact, Sen. Byron Dorgan (D-ND) introduced a “Resolution of Disapproval”–largely at the urging of Free Press and other regulatory advocates like Parents Television Council–that would overturn a half-hearted media liberalization effort undertaken by the Federal Communications Commission last December.

That FCC effort dealt with just one of the myriad regulations governing media structures in this country: the newspaper/broadcast cross-ownership rule. The newspaper/broadcast cross-ownership rule, which has been in effect since 1975, prohibits a newspaper owner from owning a radio or television station in the same media market. “No changes to the other media-ownership rules [are] currently under review,” FCC Chairman Martin noted at the time, leaving many TV and radio broadcasters wondering when they will ever get regulatory relief.

In a New York Times op-ed released at the same time as his December proposal, Martin argued that “in many towns and cities, the newspaper is an endangered species,” and that “if we don’t act to improve the health of the newspaper industry, we will see newspapers wither and die.” Moreover, he wrote, “The ban on newspapers owning a broadcast station in their local markets may end up hurting the quality of news and the commitment of news organizations to their local communities.” In other words, newspapers need the flexibility to change business arrangements and ally with others to survive.

Exhibit 1

Continue reading →

What he said:

Personally, I couldn’t care less whether Jimbo is sleeping with Rachel Marsden (other than the fact that she appears to be insane), or what they say to each other in their IM chats. I don’t care whether Jimbo has had marital problems, or whether he’s had disagreements with the foundation over his expenses. All that says to me is that he’s human, and has made mistakes.

But the implication is that because he’s made some mistakes in his personal life, that somehow Wikipedia itself is demeaned or invalidated in some way, as though someone had discovered that Mother Theresa was skimming money, or running drugs through the orphanage. To me, Jimmy Wales is nothing more than the guy who set Wikipedia in motion; it has become much more than a one-man show, if it ever was. What he does in his personal life is of no interest to me, nor do I think it’s particularly relevant to what matters about Wikipedia.

I think this is roughly akin to the argument that because Enron was cooking its books, capitalism is fatally flawed. Wikipedia is a large community of people that’s fundamentally defined by its decentralized decision-making process. Jimmy Wales has more influence than anyone else in that community, but his benevolent dictatorship is sharply constrained by the need to keep the foot soldiers happy. Whether he’s personally corrupt (and just to be clear, none of the dirt that’s been dug up thus far proves anything of the sort) or not is beside the point, he’s grown the site to the point where it could easily carry on without him.

Not quite, says my boss Ken Ferree, president of PFF, in testimony this morning before the House Committee on Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Telecommunications and the Internet. Even though there’s a heated battle going between large sports leagues and video distributors over where sports programming sits on the dial and what the price is charged for it, the bottom line is that there is no reason for the government to be called in to regulate this game. As Ken argues:

there are powerful forces acting on both sides of the bargaining equation. On the one hand, sports programming networks own extremely valuable content, which, generally speaking, distributors wish to carry. On the other hand, program distributors are under tremendous pressure to control consumer rates; limiting programming costs is perhaps the most direct means of achieving that end. The market, not regulatory authorities or appointed arbitrators, is best positioned to balance those interests.

Read Ken’s entire statement to the Committee here. [And there’s more coverage of the hearing over at Broadcasting & Cable.]

Over at Ars, I have a new piece up that draws a (somewhat provocative, perhaps) parallel between today’s copyright debates and the property rights debates of the 18th and 19th centuries:

The American property system is based on the British common law system, but colonists quickly discovered that British property law was inadequate to the realities of the New World. In England, land was scarce and titles were well established. The American colonies, in contrast, had an abundance of land but poorly-defined boundaries and inadequate record-keeping. As a result, squatting became extremely common. Landless Americans would move to the frontier, clear some land, and begin building on it without first securing a property title.

This was illegal, and governments worked hard to prevent it. The resulting conflicts made today’s battles over file sharing look tame. In 1786, when Massachusetts tried to eject squatters in Maine (a Massachusetts territory at the time) the result was what one historian describes as “something like open warfare.” Squatters refused to pay for their land or vacate it, and the government tried to forcibly evict them. One sheriff was killed trying to evict a squatter, and juries refused to convict the accused murderer.

Copyright maximalists love to draw parallels between property rights and copyrights. But if we take that analogy seriously, I think it actually leads in some places that they aren’t going to like. Our property rights system was not created by Congressional (or state legislative) fiat. Property rights in land is an organic, bottom up exercize. The job of government isn’t to dictate what the property system should look like, but to formalize and reinforce the property arrangements people naturally agree to among themselves.

The fact that our current copyright system is widely ignored and evaded is a sign, I think, that Congress has done a poor job of aligning the copyright system with ordinary individuals’ sense of right and wrong. Just as squatters 200 years ago didn’t think it was right that they be booted off land they cleared and brought under cultivation in favor of an absentee landowner who had written a check to a distant federal government, so a lot of people feel it’s unfair to fine a woman hundreds of thousands of dollars to share a couple of CDs’ worth of music. You might believe (as do I) that file sharing is unethical, just as many people believed that squatting was unethical. But at some point, Congress has no choice but to recognize the realities on the ground, just as it did with real property in the 19th century.

.

Business Week media columnist Jon Fine penned a “Requiem for Old-Time Radio” this week that illustrates the troubles facing one of America’s oldest media sectors. Fine expresses the same sort of reverence and nostalgia I often do when talking about what radio meant to some of us in our youth:

“I remember what we now call “terrestrial radio” with ridiculous fondness. I recall huddling with it long past bedtime, the volume set low, hoping to hear something I loved. Thus the truism of how radio is the most intimate medium: You’re in bed with the lights out, the music and the DJ’s voice going straight into your brain, the images created are yours alone.”

Radio really did inspire the imagination of a entire generations like that in the past. But, as Fine notes, those generations got old, and so did radio. “Realities of the music world—the explosion in both expression and availability, first on independent labels and now everywhere, thanks to the Internet—began overtaking commercial radio stations well over 20 years ago.” Indeed, as I documented in part 5 of my “Media Metrics” series, the competition for our ears has never been more intense:

Continue reading →

Gary Gygax, the father of role-playing games, died today at his home in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. As a fellow Wisconite and lover of video games–the modern forum for Gary’s roll-playing games–I have to say this is a sad day.

Wired has a post on his passing and for those of you who don’t know much about gaming and the contribution that Gygax made to the field, it’s worth reading the Wikipedia entry on his life.

Gygax with Stephen Hawking and Lieutenant Ohura on an episode of Futurama.

Though his passing isn’t a policy issue, Gygax was one of the founders of early gaming culture which has been carried through to the PC and console platforms which are under attack today. Gygax’s passing should remind us that attacks on gaming aren’t anything new. Role playing games were also attacked when they arrived on the scene. In fact, Tom Hanks starred in Mazes & Monsters, a movie based around the death of gamer James Dallas Egbert III, resulting in hype similar to the stuff we hear today about the effects of violent video games.

Today such objections to board games seem silly. Hopefully in the next decade we’ll look back on the proposed game burnings of the 90s and today as just as foolish.

Mari Silbey of MediaExperiences2Go has an interesting post about “The Changing Face of Concurrency.” She examines the various metrics companies and analysts use to study bandwidth flows or to model network activity. These include households passed, penetration ratio, concurrency ratio, and bandwidth. Concurrency represents the number of subscribers likely to be tuned in or logged on at any given time, which is obviously important for cable bandwidth measures or estimated since it is a shared network. It’s not enough to simply be examining penetration ratios or aggregate bandwidth measures when debating network management policies. Concurrency ratios give us a better way to measure what is possible on existing cable infrastructure.

More broadly speaking, the reason all this is important is because we need to have a common set of metrics when evaluating issues that come up in Net neutrality debates since opponents often use different terms and measures when discussing these issues. Anyway, just thought I would highlight her article for that reason.

Congressman Ed Markey (D-Mass) has introduced legislation aimed at ridding the cell phone world of the much criticized practicies of phone subsidies, long-term contracts, and termination fees. In the name of contract “consistency” Markey’s bill mandates that cell companies offer alternative plans that contain no subsidy for the handset and plans that offer month-to-month service.

Congressman Ed Markey (D-Mass) has introduced legislation aimed at ridding the cell phone world of the much criticized practicies of phone subsidies, long-term contracts, and termination fees. In the name of contract “consistency” Markey’s bill mandates that cell companies offer alternative plans that contain no subsidy for the handset and plans that offer month-to-month service.

The bill contains a long section of “findings,” which are intended to point out what, from Rep. Markey’s perspective, are the illogical practices of cell phone providers. However, if you look at the issue of termination fees, you’ll find that Rep. Markey’s bill ignores the role of competition in decreasing costs to consumers and fails to take into account long-term investment in increasing nation-wide wireless capacity.

The bill claims that termination fees “Do not reflect the cost of recovering the monetary amount of a bundled mobile device or any other expenditure for customer acquisition.” The most glaring problem with this finding is that it’s already outed. Sprint, which is currently hemorrhaging money, instituted a new policy in November that allows customers to change plans without extending contracts and prorates termination fees. This came on the heels of similar announcements from Verizon and AT&T in October of last year. So, the bill’s $175 average termination fee figure is likely an incorrect one based on old policies.

But termination fees don’t just serve the purpose of cost recovery, they also provide an incentive for customers staying loyal to their wireless provider and giving these providers revenue predictability. With predictable revenues, it’s easier for cell phone network companies to get the financing they need to build the multi-billion dollar networks of tomorrow. Rep. Markey’s bill may save consumers in the short-term, but in the long run adding volatility to the marketplace will stem investment and slow the roll-out of 4G and Wi-Max networks.

We often talk about the unintended consequences of legislation in our work at CEI–this is a prime example of some very significant and costly unintended consequences that will ultimately hurt consumers and threatens to put America behind the curve on cell phone technology.

Rep. Markey’s bill also deals with wireless broadband, coverage maps, and spectrum efficiency. Topics that Ryan Radia and I will be addressing in future posts.

Congressman Ed Markey (D-Mass) has introduced legislation aimed at ridding the cell phone world of the much criticized practicies of phone subsidies, long-term contracts, and termination fees. In the name of contract “consistency” Markey’s bill mandates that cell companies offer alternative plans that contain no subsidy for the handset and plans that offer month-to-month service.

Congressman Ed Markey (D-Mass) has introduced legislation aimed at ridding the cell phone world of the much criticized practicies of phone subsidies, long-term contracts, and termination fees. In the name of contract “consistency” Markey’s bill mandates that cell companies offer alternative plans that contain no subsidy for the handset and plans that offer month-to-month service. The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.