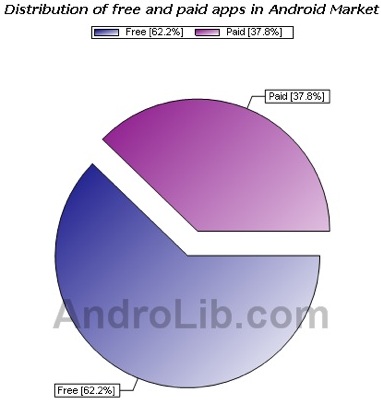

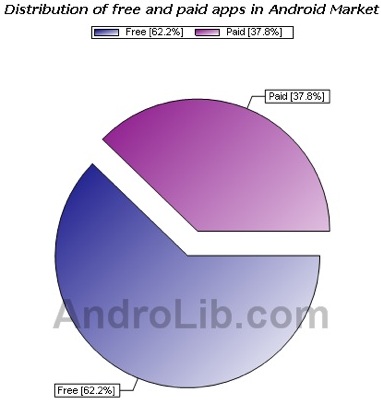

Oh yeah, that was me. And a lot of others. Well, we were wrong. The mobile app store market (Apple, Android, etc) is brimming with a bonanza of micro-business opportunities for producers and consumers alike. I am consistently amazing by the range of offerings available today, the vast majority of which remain free of charge. But what is more impressive is the growing array of applications and games available for mere pennies. Sure, some are more than a buck — but not that much more. I was just looking through the 40+ apps that I’ve got on my Droid right now (not really sure how many I’ve downloaded overall since I’ve deleted a lot) and I would guess that I paid for at least 25% of them–many after being “upsold” by first trying the free versions and then buying. Yes, I know there continues to be a debate about what counts as a “micropayment,” but the fact that so many more people are paying just a couple of bucks or less for content in these mobile app stores suggests that its only going to easier for people to pay even smaller sums for content in coming years.

What got me thinking about all this was slide #75 in Mary Meeker’s latest slideshow about Internet trends. The Morgan Stanley web guru notes that users are more willing to pay for content on mobile devices than they are on desktop computers for a number of reasons, but the first of which she listed was: “Easy-to-Use/Secure Payment Systems — embedded systems like carrier billing and iTunes allow real-time payment.” The important point here is that the combination of these slick, well-organized online app stores + secure, super-easy billing systems have combined to overcome the so-called”mental transaction cost problem,” at least to some extent. We’re not nearly as reluctant today to surf away when something says “$0.99” on our screen. Increasingly, we’re hitting the “Buy” button.

Continue reading →

Continue reading →

I’ve always generally agreed with the conventional wisdom about micropayments as a method of funding online content or services: Namely, they won’t work. Clay Shirky, Tim Lee, and many others have made the case that micropayments face numerous obstacles to widespread adoption. The primary issue seems to be the “mental transaction cost” problem: People don’t want to be diverted–even for just a few seconds–from what they are doing to pay a fee, no matter how small. [That is why advertising continues to be the primary monetization engine of the Internet and digital services.]

That being said, I keep finding examples of how micropayments do work in some contexts and it has kept me wondering if there’s still a chance for micropayments to work in other contexts (like funding media content). For example, I mentioned here before how shocked I was when I went back and looked at my eBay transactions for the past couple of years and realized how many “small-dollar” purchases I had made via PayPal (mostly dumb stickers and other little trinkets). And the micropayment model also seems to be doing reasonably well in the online music world. In January 2009, Apple reported that the iTunes Music Store had sold over 6 billion tracks.

That being said, I keep finding examples of how micropayments do work in some contexts and it has kept me wondering if there’s still a chance for micropayments to work in other contexts (like funding media content). For example, I mentioned here before how shocked I was when I went back and looked at my eBay transactions for the past couple of years and realized how many “small-dollar” purchases I had made via PayPal (mostly dumb stickers and other little trinkets). And the micropayment model also seems to be doing reasonably well in the online music world. In January 2009, Apple reported that the iTunes Music Store had sold over 6 billion tracks.

And then there are mobile application stores. Just recently I picked up a Droid and I’ve been taking advantage of the rapidly growing Android marketplace, which recently hit the 20,000 apps mark. Like Apple’s 100,000-strong App Store, there’s a nice mix of paid and free apps, and even though I’m downloading mostly freebies, I’ve started buying more paid apps. Many of them are “upsells” from free apps I downloaded. In most cases, they are just 99 cents. A few examples of paid apps I’ve downloaded or considered buying: Stocks Pro, Mortgage Calc Pro, Currency Guide, Photo Vault, Weather Bug Elite, and Find My Phone. And there are all sorts of games, clocks, calendars, ringtones, heath apps, sports stuff, utilities, and more that are 99 cents or $1.99. Some are more expensive, of course.

Continue reading →

Micropayments are an idea that simply won’t die. Every few years, there’s a resurgence of interest in the idea. Critics predict they won’t work. The critics are then proved right, as companies founded to promote micropayments inevitably go belly-up.

The latest iteration comes courtsey of Time magazine, which recently saw fit to run a cover story about how micropayments will save newspapers. And Shirky once again steps up to the plate to explain why micropayments won’t work any better in 2009 than they did in 1996, 2000, or 2003. (I wrote up Shirky’s arguments here and here) But for my money, the best response to the Isaccson piece is at the Abstract Factory blog:

Why did Time’s editors choose to run this article, rather than, for example, an article by Shirky or Odlyzko or any number of people who would write something more clueful? I hypothesize two reasons. First, Time’s editors themselves do not have a clue, and also do not have any problem publishing articles on a subject they have no clue about. Second, look at the author blurb at the bottom of the article (emphasis mine):

Isaacson, a former managing editor of TIME, is president and CEO of the Aspen Institute and author, most recently, of Einstein: His Life and Universe..

When you’re a member of the club, your buddies will publish any old crap you write; better you than some stupid professor nobody knows. We’ve seen this before.

I mentioned irony earlier. Isaacson has filigreed the irony with extraordinary precision. His article is inferior to material produced for free online by people who draw their paychecks from other sources (Shirky and Odlyzko are both professors who also work(ed) in the private technology sector). Furthermore, it is inferior as a direct consequence of structural weaknesses of traditional magazines. Despite its inferior quality, it presumes its own superior status by ignoring or dismissing contributions to the discussion which occurred outside of traditional “journalistic” media. Finally, taking that superiority as a given, it argues, poorly, that people ought to pay money for products like itself, because (quoting Bill Gates) nobody can “afford to do professional work for nothing.”

In short, Isaacson’s article not only fails to make its case, it actively undermines its own case while doing so.

Quite so. There’s more good stuff where that came from.

I have generally agreed with Clay Shirky (and Tim) that micropayments either don’t work very well or just aren’t needed given other pricing options / business models. But my eBay activity over the past few years has made me reconsider. I was going back through some of my past eBay purchases tonight and leaving feedback and I realized that I have made dozens of micropayments in recent months for all sorts of nonsense (stickers, posters, small car parts, Legos for my kids, magazines, and much more). Most of these items are just a few bucks, and many don’t even break the 99-cent threshold. I think that qualifies as micropayment material. And certainly I am not the only one engaged in such micro-transactions because there are countless items on eBay for a couple of bucks or less.

Of course, just because micropayments and PayPal work marvelously in the context of the used junk and trinkets we find on eBay, that does not necessarily mean they will work as effectively for many forms of media content. Advertising or flat user fees are probably still preferable since consumers don’t like the hassles associated with micropayments. Still, they seem to be working fine on eBay, so it would be wrong to claim that they never work online.

I just came across this great article from 2000 by Clay Shirky. He argues that micropayments are a bad idea that are doomed to fail because they economize on extremely cheap resources (bandwidth, content) at the expense of a relatively valuable resource–the user’s time. He persuasively argues that there’s no such thing as a no-brainer transaction–if a micropayment is large enough to be worth the bother to the seller, then it’s large enough that the buyer will want to consider it before approving it. But the time and annoyance of having to think before clicking on every link the user encounters might vastly outweigh the value of the penny being transacted.

Another way to put this, I think, is that we already have micropayments: they’re called ads. Users pay for content, not with cash payments, but with their time– giving a split-second of attention to the ads on the page as they read the content. And it turns out that in most cases, advertisers are willing to pay more for ad impressions than users are willing to pay for content. And users prefer ads to micropayments because micropayments take more time and hassle to deal with than ads that can be easily and safely ignored.

Over a month ago I testified at the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee hearing on Bitcoin. I’ve been asked by the committee to submit answers to additional questions, and I thought I’d try to tap into the Bitcoin community’s wisdom by posting here the questions and my draft answers and inviting you to post in the comments any suggestions you might have. I’d especially appreciate examples of innovative uses of Bitcoin or interesting potential business cases. Thanks for your help! Continue reading →

A common question among smart Bitcoin skeptics is, “Why would one use Bitcoin when you can use dollars or euros, which are more common and more widely accepted?” It’s a fair question, and one I’ve tried to answer by pointing out that if Bitcoin were just a currency (except new and untested), then yes, there would be little reason why one should prefer it to dollars. The fact, however, is that Bitcoin is more than money, as I recently explained in Reason. Bitcoin is better thought of as a payments system, or as a distributed ledger, that (for technical reasons) happens to use a new currency called the bitcoin as the unit of account. As Tim Lee has pointed out, Bitcoin is therefore a platform for innovation, and it is this potential that makes it so valuable.

Eric Posner is one of these smart skeptics. Writing in Slate in April he rejected Bitcoin as a “fantasy” because he felt it didn’t make sense as a currency. Since then it’s been pointed out to him that Bitcoin is more than a currency, and today at the New Republic he asks the question, “Why would you use Bitcoin when you can use PayPal or Visa, which are more common and widely accepted?”

He answers his own question, in part, by acknowledging that Bitcoin is censorship-resistant. As he puts it, “If you live in a country with capital controls, you can avoid those[.]” So right there, it seems to me, is one good reason why one might want to use Bitcoin instead of PayPal or Visa. Another smart skeptic, Tyler Cowen, acknowledges this as well, even if only to suggest that the price of bitcoins will fall “if/when China fully liberalizes capital flows[.]”

Continue reading →

Washington Post columnist Ezra Klein had a terrific column yesterday (Human Knowledge, Brought to You By…) on one of my favorite subjects: how advertising is the great subsidizer of the press, media, content, and online services. Klein correctly notes that “our informational commons, or what we think of as our informational commons, is, for the most part, built atop a latticework of advertising platforms. In that way,” he continues, “it’s possible that no single industry — not newspapers nor search engines nor anything else — has done as much to advance the storehouse of accessible human knowledge in the 20th century as advertisers. They didn’t do it because they are philanthropists, and they didn’t do it because they love information. But they did it nevertheless.”

Quite right. As I noted in my recent Charleston Law Review article on “Advertising, Commercial Speech & First Amendment Parity,” media economists have found that advertising has traditionally provided about 70% to 80% of support for newspapers and magazines, and advertising / underwriting has entirely paid for broadcast TV and radio media. And it goes without saying that advertising has been an essential growth engine for online sites and services. How is it that we’re not required to pay per search, or pay for most online news services, or shell out $19.95 a month for LinkedIn, Facebook, or other social media services? The answer, of course, is advertising. Thus, Klein notes, while “we see [] advertising as a distraction… without the advertising, the information wouldn’t exist. So the history of information, in the United States at least, is the history of platforms that could support advertising.”

And the sustaining power of advertising for new media continues to grow. As I noted in my law review article: Continue reading →

I’m reading David Brin’s 1998 classic [The Transparent Society](http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0738201448/ref=as_li_ss_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=jerrybritocom&linkCode=as2&camp=217145&creative=399349&creativeASIN=0738201448) and I’d like to share a passage that I found especially interesting in light of the [recent Do-Not-Track bill](http://thehill.com/blogs/hillicon-valley/technology/160035-rockefeller-unveils-do-not-track-bill) introduced by Sen. Rockefeller.

On this blog, Adam Thierer has often written about the [implicit quid pro quo](http://www.google.com/search?q=site:techliberation.com+quid+pro+quo) between tracking and free online services. It seems to me that many folks find this an abstract concept. Here is Brinn writing in the late 90s about the possibility of an explicit quid pro quo:

>An Economy of Micropayments? I cannot predict whether such an experiment would succeed, though using a “carrot”—or what chaos theorists call an “attractor state”—offers better prospects than the [IP owner’s] coalition’s present strategy of saber rattling and making hollow legal threats. In fact, the same approach might be used to deal with other aspects of “information ownership,” even down to the change of address you file with the post office. Perhaps someday advertisers and mail-order corporations will pay fair market value for each small use, either directly to each person listed or through royalty pools that assess users each time they access data on a given person. Or we might apply the concept of “trading-out”: getting free time at some favorite per-use site in exchange for letting the owners act as agents for our database records. It could be beneficial to have database companies competing with each other, bidding for the right to handle our credit dossiers, perhaps by offering us a little cash, or else by letting us trade our data for a little fun. Proponents of such a “micropayment economy” contend that the process will eventually become so automatic and computerized that it effectively fades into the background. People would hardly notice the dribble of royalties slipping into their accounts when others use “their” facts—any more than they would note the outflowing stream of cents they pay while skimming on the Web.

That is essentially what happened, except without all the transactions costs. It seems to me that all Do Not Track will do is introduce the transactions costs that we have so far avoided to the benefit of innovation. Who will this change benefit? The few people who are not willing to make the trade and who today have [options to opt out](http://adblockplus.org/). This leaves the majority of us who are willing to make the bargain in a very un-Coasean world.

As I’ve mentioned here previously, PFF has been rolling out a new series of essays examining proposals that would have the government play a greater role in sustaining struggling media enterprises, “saving journalism,” or promoting more “public interest” content. We’re releasing these as we get ready to submit a big filing in the FCC’s “Future of Media” proceeding (deadline is May 7th). Here’s a podcast Berin Szoka and I did providing an overview of the series and what the FCC is doing.

In the first installment of the series, Berin and I critiqued an old idea that’s suddenly gained new currency: taxing media devices or distribution systems to fund media content. In the second installment, I took a hard look at proposals to impose fees on broadcast spectrum licenses and channeling the proceeds to a “public square channel” or some other type of public media or “public interest” content.

In our latest essay, “The Wrong Way to Reinvent Media, Part 3: Media Vouchers,” Berin and I consider whether it is possible to steer citizens toward so-called “hard news” and get them to financially support it through the use of “news vouchers” or “public interest vouchers”? We argue that using the tax code to “nudge” people to support media — while less problematic than direct subsidies for the press — will likely raise serious issues regarding eligibility and be prone to political meddling. Moreover, it’s unlikely the scheme will actually encourage people to direct more resources to hard news but instead just become a method of subsidizing other content they already consume.

I’ve attached the entire essay down below.

Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.