A year ago, I filed a joint amicus brief with the Electronic Frontier Foundation urging the Supreme Court to overturn California’s paternalistic law on the dangerous grounds that videogame depictions of violence constituted “obscenity” unprotected by the First Amendment. Fortunately, we won. Thus, the First Amendment protects all media, while parents have a variety of tools available to them to limit what content their kids can consume, or games they can play.

But in case you’re wondering what the world might look like had the decision gone the other way, check out the contrast between the US version of Maroon 5’s hit song “Misery” and the UK version. First, here’s the (raucous and sexy) US version:

Now, here’s the UK version, where the sexually suggestive parts remain (kids love that stuff) but all the “violent” parts have been replaced with, or covered by, ridiculous cartoon images. Really, it’s just too funny. The best part is where the knife she uses to stab the gaps between his fingers on the table has been replaced with a cartoon ice cream cone. Don’t try that at home, kids—you’ll make a chocolatey mess!

In case you were wondering, the US version has nearly 47 million views while the UK version has a paltry half million views. Gee, I wonder why… (Actually, I suspect that most of the UK version’s viewers watched it because it’s so hilariously stupid.)

Parents can easily turn on YouTube’s safe search tool to block many objectionable videos—and lock it so kids can’t turn it off. (CBS made a great video explaining how to do this for parents.)

Given the enormous scale of videos on YouTube, Safe Search isn’t perfect: It wouldn’t block this particular video, probably because the video doesn’t trigger any obvious keywords like “porn” and not enough users have complained about it to bring it to the attention of Google’s human review team. But it’s easy to find a wide variety of tools that will restrict kids’ access to specific domains, such as YouTube. This allows parents to supervise their kids’ use of those sites.

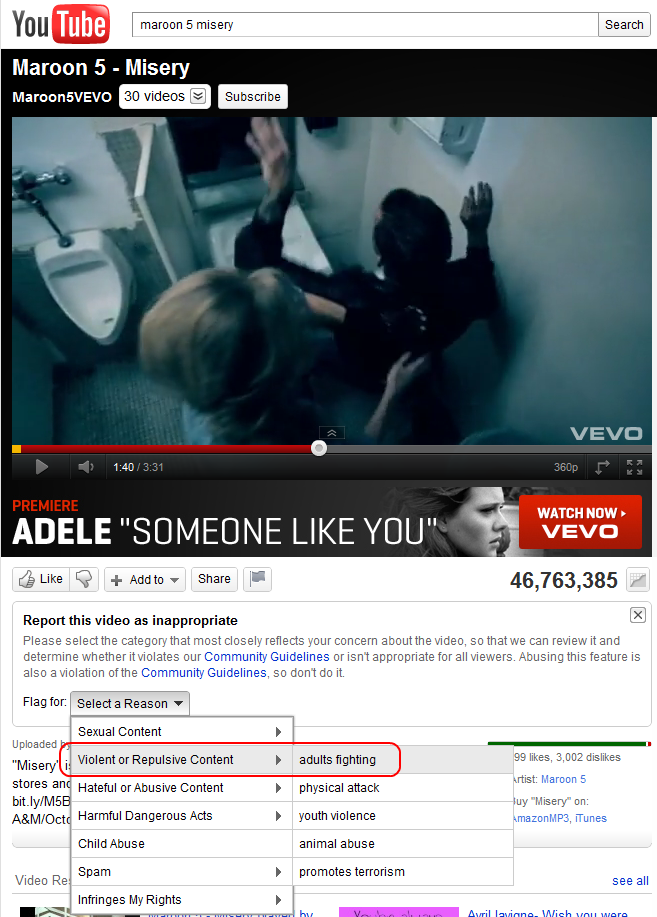

Now, if you don’t think Google’s blocking enough, it’s easy to flag a video as inappropriate by clicking on the flag below the video, which expands a dialogue box, like so:

Like all web tools, parental controls are always evolving. In the next update, I’d love to see Google allow parents to restrict their kids’ use of YouTube to certain playlists, either set up by the parents themselves or by, say, third party groups dedicated to screening content for parents. That would empower parents to configure YouTube as they see fit and trust that their kids can use the site wisely, without parents having to watch the whole time or rely on a necessarily imperfect (but still pretty darn good) tool like SafeSearch.

As a constitutional matter, the important point here is the one Adam Thierer always makes: parental control tools need not be perfect to be preferable to government regulation. That’s an (accurate) paraphrase of the Supreme Court’s clear 2000 decision on this subject in U.S. v. Playboy:

It is no response that voluntary blocking requires a consumer to take action, or may be inconvenient, or may not go perfectly every time. A court should not assume a plausible, less restrictive alternative would be ineffective; and a court should not presume parents, given full information, will fail to act.

That’s freedom for you! As the Court went on to add:

Technology expands the capacity to choose; and it denies the potential of this revolution if we assume the Government is best positioned to make these choices for us.

Parental controls aren’t perfect but they’re getting better all the time. Would you rather live in the UK’s world of crude, cartoonish and clumsy censorship?

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.