Early one morning, the Civil War crashed into my bedroom. A loud popping noise crackled just outside our window . . . I went to the window and saw men in gray uniforms firing muskets on the road in front of our house.

These men in grey uniforms weren’t soldiers, not even actors playing soldiers—these men were reenactors. They had found their way into the front yard of writer Tony Horwitz, inspiring him to write the bestselling Confederates in Attic.

For a new generation of civil war buffs there’s a way to reenact without the smell of bacon grease, gunpowder, and coffee grounds hanging in the air. Buffs old and young have many things in common—namely, abundant free time and obsessive attention to detail—but the younger breed prefers keyboards to Colt revolvers.

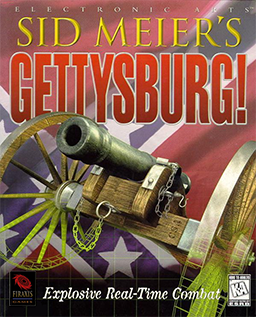

Sid Meier’s Gettysburg, released in 1997, marked a significant step toward satisfying generation X reenactors, but it still didn’t quite scratch the itch. More recent releases, like the History Channel’s cleverly named History Channel: Civil War was decried by gamers as boring while buffs were annoyed at its inaccuracy.

Sid Meier’s Gettysburg, released in 1997, marked a significant step toward satisfying generation X reenactors, but it still didn’t quite scratch the itch. More recent releases, like the History Channel’s cleverly named History Channel: Civil War was decried by gamers as boring while buffs were annoyed at its inaccuracy.

Because of all of this, a new community was born—or at least a sub-community.

Since the early days of video games, hobbyists have modified commercial video games—creating their own specialized versions with unique attributes and themes. “Modding,” as it’s often called, naturally appeals to the meticulous nature of the reenactor. Obsessions with detail and historical accuracy can now be expressed not only in recreating clothing and weaponry, but entire battlefield landscapes.

Electronic Arts’ Battlefield 1942 has been reworked to produce Battlefield 1861. Microsoft’s Rise of Nations as well as its Age of Empires series have also been re-worked to produce incredibly detailed Civil War games. Some of these efforts are the result of one lonely man’s hobby, but more often they are the result of a team of a dozen or more developers coordinating their efforts using online forums and email lists.

This kind of community of obsessive hobbyists is part of the reason why I don’t believe the PC gaming industry is anywhere near its death. There is such a huge amount of dark data out there—data that exists, but that hasn’t been aggregated into a useful form just yet. Much of the PC gaming community is non-commercial, unmeasured, but likely terrifically huge.

I’ve been research modding communities recently and made some interesting discoveries. For example, Quake Live, a new service of id Software, is very popular—odd thing is, it supports a game that’s nine years old.

ID’s Marty Stratton recently spoke about Quake Live, noting:

I was very happy to find over 100,000 people signed up for our beta with no promotion, no advertising.

This sort of thing is unique to PCs—though it may develop with console communities given more time. However, I think the fact that PC games are played on the same machines that we also use to email, participate in online forums, mod software, and all variety of other activities, creates a greater opportunities for PC games to develop dynamic communities that attain cult-like status.

I’d appreciate any solid numbers on the size of modding communities or even vanilla games are somewhat old. I find it incredibly interesting. Thanks in advance for any help.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.