by Berin Szoka & Adam Thierer, Progress Snapshot 5.11 (PDF)

Ten years ago, Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman lamented the “Business Community’s Suicidal Impulse:” the persistent propensity to persecute one’s competitors through regulation or the threat thereof. Friedman asked: “Is it really in the self-interest of Silicon Valley to set the government on Microsoft?” After yesterday’s FCC vote’s to open a formal “Net Neutrality” rule-making, we must ask whether the high-tech industry—or consumers—will benefit from inviting government regulation of the Internet under the mantra of “neutrality.”

The hatred directed at Microsoft in the 1990s has more recently been focused on the industry that has brought broadband to Americans’ homes (Internet Service Providers) and the company that has done more than any other to make the web useful (Google). Both have been attacked for exercising supposed “gatekeeper” control over the Internet in one fashion or another. They are now turning their guns on each other—the first strikes in what threatens to become an all-out, thermonuclear war in the tech industry over increasingly broad neutrality mandates. Unless we find a way to achieve “Digital Détente,” the consequences of this increasing regulatory brinkmanship will be “mutually assured destruction” (MAD) for industry and consumers.

New Fronts in the Neutrality Wars

The FCC’s proposed rules would apply to all broadband providers, including wireless, but not to Google or many other players operating in other layers of the Net who favor such broadband-specific rules. With this rulemaking looming, AT&T came after Google with letters to the FCC in late September and then another last week accusing the company of violating neutrality principles in their business practices and arguing that any neutrality rules that apply to ISPs should apply equally to Google’s panoply of popular services. In particular, AT&T accused Google of “search engine bias,” suggesting that only government-enforced neutrality mandates could protect consumers from Google’s supposed “monopolist” control.

The promise made yesterday by the FCC—to only apply neutrality principles to the infrastructure layer of the Net—is hollow and will ultimately prove unenforceable. Continue reading →

Last Wednesday, Holman Jenkins penned a column in The Wall Street Journal about net neutrality (Adam discussed it here). In response, I have a letter to the editor in today’s The Wall Street Journal:

To the Editor:

Mr. Jenkins suggests that Google would likely “shriek” if a startup were to mount its servers inside the network of a telecom provider. Google already does just that. It is called “edge caching,” and it is employed by many content companies to keep costs down.

It is puzzling, then, why Google continues to support net neutrality. As long as Google produces content that consumers value, they will demand an unfettered Internet pipe. Political battles aside, content and infrastructure companies have an inherently symbiotic relationship.

Fears that Internet providers will, absent new rules, stifle user access to content are overblown. If a provider were to, say, block or degrade YouTube videos, its customers would likely revolt and go elsewhere. Or they would adopt encrypted network tunnels, which route around Internet roadblocks.

Not every market dispute warrants a government response. Battling giants like Google and AT&T can resolve network tensions by themselves.

Ryan Radia

Competitive Enterprise Institute

Washington

To be sure, the market for residential Internet service is not all that competitive in some parts of the country — Rochester, New York, for instance — so a provider might in some cases be able to get away with unsavory practices for a sustained period without suffering the consequences. Yet ISP competition is on the rise, and a growing number of Americans have access to three or more providers. This is especially true in big cities like Chicago, Baltimore, and Washington D.C.

Instead of trying to put a band-aid on problems that stem from insufficient ISP competition, the FCC should focus on reforming obsolete government rules that prevent ISP competition from emerging. Massive swaths of valuable spectrum remain unavailable to would-be ISP entrants, and municipal franchising rules make it incredibly difficult to lay new wire in public rights-of-way for the purpose of delivering bundled data and video services.

FOXNews.com has just published an editorial that I penned about Monday’s net neutrality announcement from the FCC.

by Ryan Radia

The federal government may gain broad new powers to regulate Internet providers next month if Federal Communications Commission Chairman Julius Genachowski gets his way. In a milestone speech on Monday, Genachowski proposed sweeping new regulations that would give the FCC the formal authority to dictate application and network management practices to companies that offer Internet access, including wireless carriers like AT&T and Verizon Wireless.

providers next month if Federal Communications Commission Chairman Julius Genachowski gets his way. In a milestone speech on Monday, Genachowski proposed sweeping new regulations that would give the FCC the formal authority to dictate application and network management practices to companies that offer Internet access, including wireless carriers like AT&T and Verizon Wireless.

Genachowski’s proposed rules would make good on a pledge that President Obama made in his campaign to enshrine net neutrality as law. The announcement was met with cheers by a small but vocal crowd of activists and academics who have been pushing hard for net neutrality for years. But if bureaucrats and politicians truly care about neutrality, they would be wise to resist calls to expand the government’s power over private networks. Instead, policymakers should recognize that it is far more important for government to remain neutral to competing business models — open, closed, or any combination thereof.

Continue reading →

Forbes.com has just published an editorial that Berin Szoka and I penned about yesterday’s net neutrality announcement from the FCC.

by Adam Thierer & Berin Szoka

There was a time, not so long ago, when the term “Internet Freedom” actually meant what it implied: a cyberspace free from over-zealous legislators and bureaucrats. For a few brief, beautiful moments in the Internet’s history (from the mid-90s to the early 2000s), a majority of Netizens and cyber-policy pundits alike all rallied around the flag of “Hands Off the Net!” From censorship efforts, encryption controls, online taxes, privacy mandates and infrastructure regulations, there was a general consensus as to how much authority government should have over cyber-life and our cyber-liberties. Simply put, there was a “presumption of liberty” in all cyber-matters.

Those days are now gone; the presumption of online liberty is giving way to a presumption of regulation. A massive assault on real Internet freedom has been gathering steam for years and has finally come to a head. Ironically, victory for those who carry the banner of “Internet Freedom” would mean nothing less than the death of that freedom.

We refer to the gradual but certain movement to have the federal government impose “neutrality” regulation for all Internet actors and activities—and in particular, to yesterday’s announcement by Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Chairman Julius Genachowski that new rules will be floated shortly. “But wait,” you say, “You’re mixing things up! All that’s being talked about right now is the application of ‘simple net neutrality,’ regulations for the infrastructure layer of the net.” You might even claim regulations are not really regulation but pro-freedom principles to keep the net “free and open.”

Such thinking is terribly short-sighted. Here is the reality: Because of the steps being taken in Washington right now, real Internet Freedom—for all Internet operators and consumers, and for economic and speech rights alike—is about to start dying a death by a thousand regulatory cuts. Policymakers and activists groups are ramping up the FCC’s regulatory machine for a massive assault on cyber-liberty. This assault rests on the supposed superiority of common carriage regulation and “public interest” mandates over not just free markets and property rights, but over general individual liberties and freedom of speech in particular. Stated differently, cyber-collectivism is back in vogue—and it’s coming very soon to a computer near you! Continue reading →

If I can amplify a bit on a post at the Cato blog earlier today, I want to clarify that I fully agree some of the ISP behaviors that net neutrality proponents have identified as demanding a regulatory response really are seriously problematic. My point of departure is that I’d rather see if there are narrower grounds for addressing the objectionable behaviors than making sweeping rules about network architecture. So in the case of Comcast’s throttling of BitTorrent, which is the big one that seems to confirm the fears of the neutralists, I think it’s significant that for a long while the company was—”lying about” assumes intent, so I’ll charitably go with “misrepresenting”—their practices. And I don’t think you need any controversial premises about optimal network management to think that it’s impermissible for a company to charge a fee for a service, and then secretly cripple that service. So without even having to hit the more controversial “nondiscrimination” principle Julius Genachoswki proposed on Monday, you can point to this as a failure of the “transparency” principle, about which I think there’s a good deal more consensus. Now, there are bigger guns out there looking for dodgy filtering practices these days, so I’d expect the next attempt at this sort of thing to get caught more quickly, but by all means, enforce transparency about business practices too. Consumers have a right to get the service they’ve bought without having to be 1337 haxx0rz to discover how they’re being shortchanged. But before we get the feds involve in writing code for ISP routers, I’d like to see whether that proves sufficient to limit genuinely objectionable deviations from neutrality.

There’s a hoary rule of jurisprudence called the canon of constitutional avoidance. It means, very crudely, that judges don’t decide broad constitutional questions—they don’t go mucking with the basic architecture of the legal system—when they have some narrower grounds on which to rule. So if, for instance, there are two reasonable interpretations of a statute, one of which avoids a potential conflict with a constitutional rule, judges are supposed to prefer that interpretation. It’s not always possible, of course: Sometime judges have to tackle the big, broad questions. But it’s supposed to be something of a last resort. Lawyers and civil liberties advocates, of course, tend to get more animated by those broad principles, whether the First Amendment or end-to-end. But there’s often good reason to start small—to look to the specific fact patterns of problem cases and see whether there are narrower bases for resolution. It may turn out that in the kinds of cases that neutralists rightly warn could harm innovation, it’s not one big principle, but a diverse array of responses or fixes that will resolve the different issues. In a case like this one, perhaps a mix of mandated transparency, consumer demand, and user adaptation (e.g. encrypting traffic) will get you the same (or a better) result than an architectural mandate.

Continue reading →

The Tennis Channel and ESPN have teamed up to offer live coverage of the US Open online. Not only is this a wonderful thing for consumers, but it also demonstrates just how easily content creators (including traditional television programming networks) can completely bypass cable companies, who once supposedly used their “bottleneck” power to act as “gatekeepers” over the content Americans could receive. If this was ever true, it certainly isn’t true in the era of Internet video!

The venture will, of course, be ad-supported. But just how much content such a model can support will depend heavily on whether Internet video programming distributors like this venture (or Hulu.com) will be able to personalize the ads shown on their videos based on the likely interests of users. Ad industry observer David Hallerman has predicted that spending on behavioral advertising:

is projected to reach $1.1 billion in 2009 and $4.4 billion in 2012 [a quarter of U.S. display advertising].The prime mover behind this rapid increase will be the mainstream adoption of online video advertising, which will increasingly require targeting to make it cost-effective.

The problem isn’t just the expense involved in streaming online video, it’s that contextually targeting advertising (based on keywords) is easy when the content is text but far more difficult when the content is video.

So if you’re hoping to cut the cord to cable and save the expense of a monthly cable subscription, you’d better hope the privacy zealots don’t wipe out advertising model necessary to make Internet video a true substitute for traditional subscription video sources!

The D.C. Circuit has struck down as arbitrary and capricious the FCC’s “cable cap.” The cap prevented a single cable operator from serving more than 30% of U.S. homes—precisely the same percentage limit struck down by the court in 2001. The court ruled that the FCC had failed to demonstrate that “allowing a cable operator to serve more than 30% of all cable subscribers would threaten to reduce either competition or diversity in programming.”

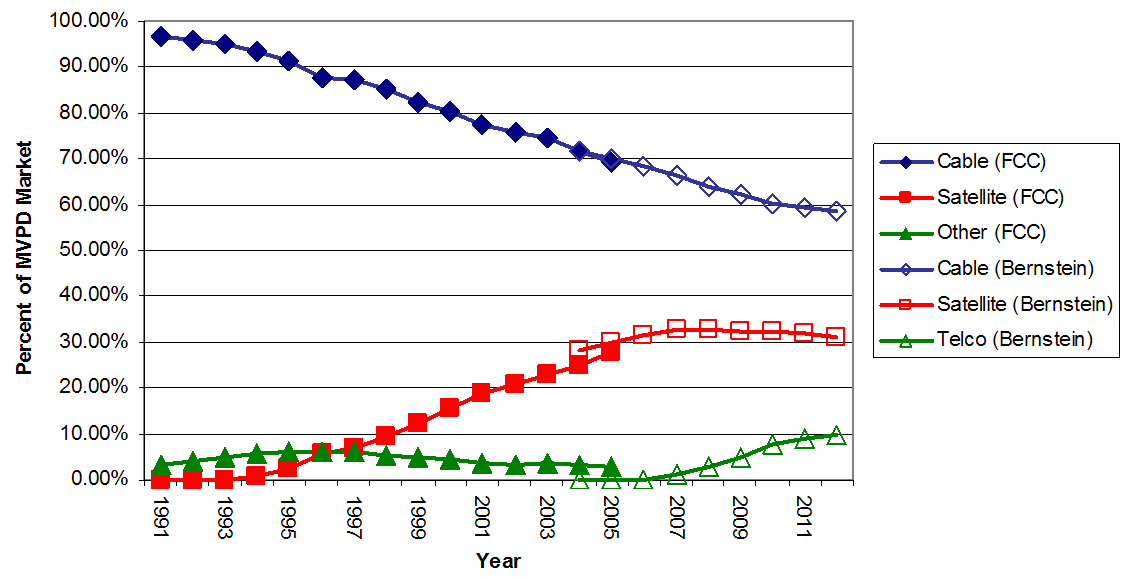

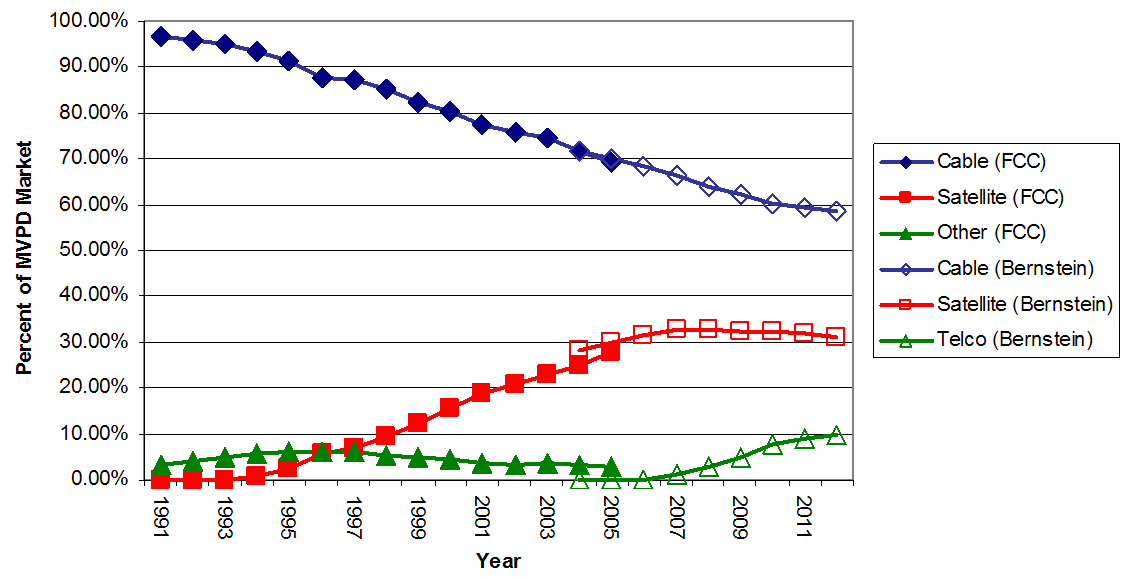

The court’s decision rested on the two critical charts (both generated by my PFF colleague Adam Thierer in his excellent Media Metrics special report) at the heart of the PFF amicus brief I wrote with our president, Ken Ferree:

First, the record is replete with evidence of ever increasing competition among video providers: Satellite and fiber optic video providers have entered the market and grown in market share since the Congress passed the 1992 Act, and particularly in recent years. Cable operators, therefore, no longer have the bottleneck power over programming that concerned the Congress in 1992.

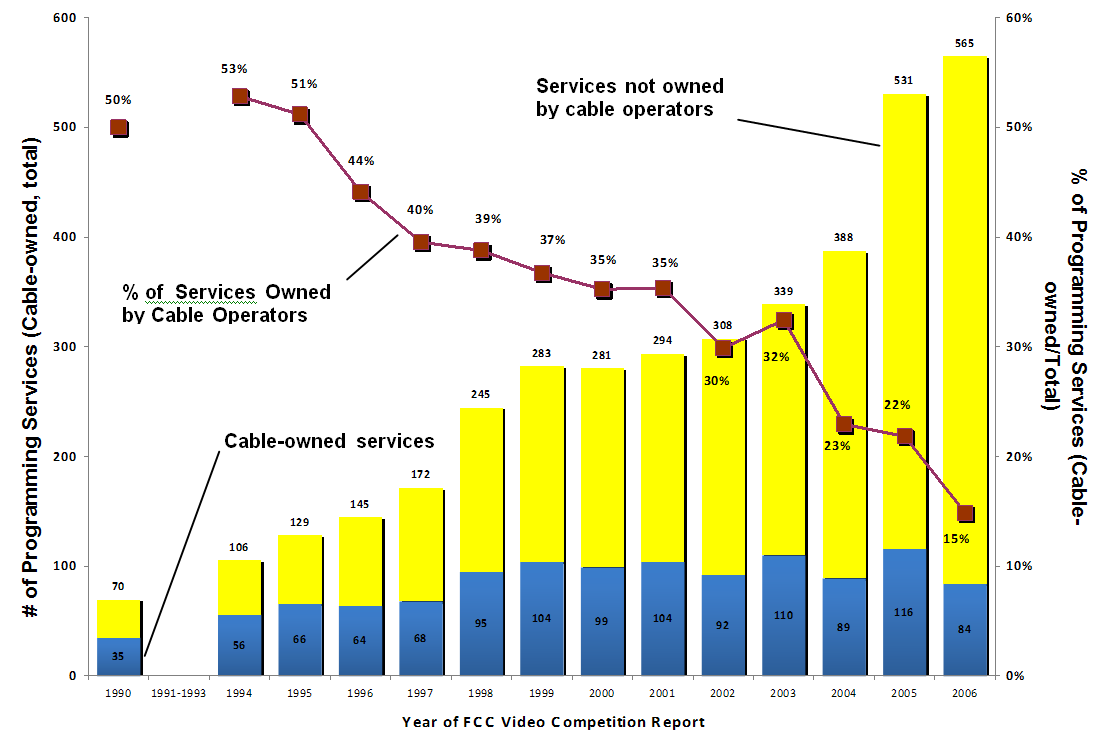

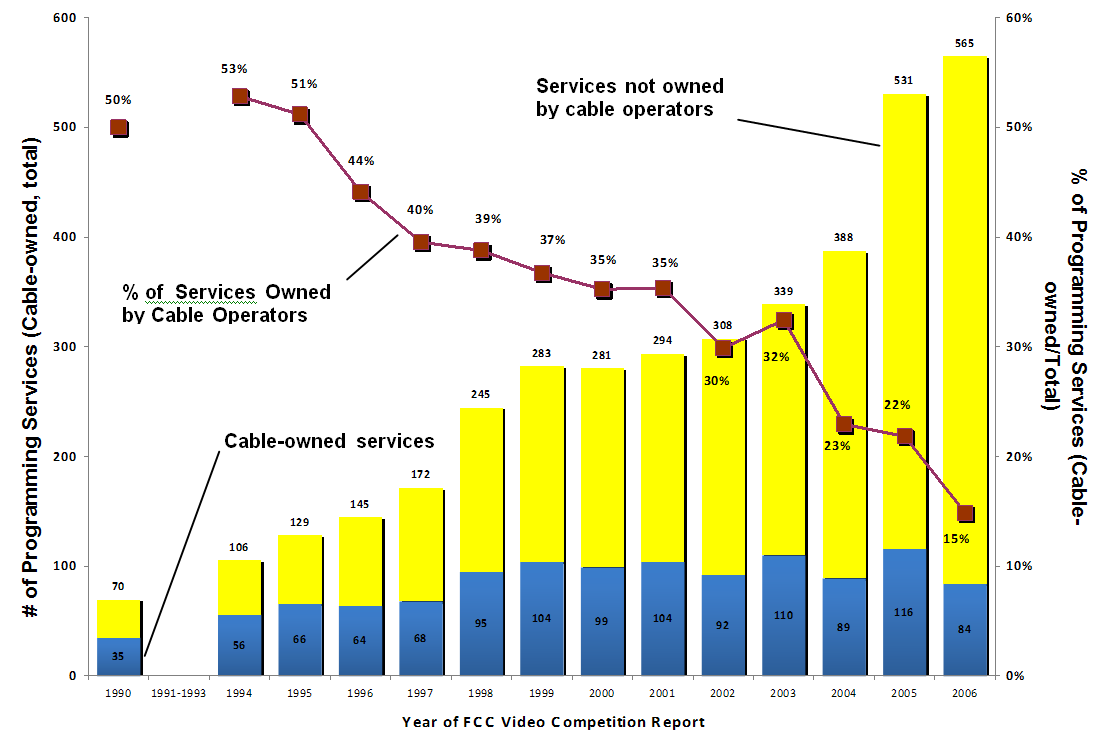

Second, over the same period there has been a dramatic increase both in the number of cable networks and in the programming available to subscribers.

Our chart shows the explosion in the number of programmers (though not the total amount of programming), as well as the falling rate of affiliation between cable operators and programmers, which was among the prime factors motivating Congress when it authorized a cable cap in the 1992 Cable Act:

Continue reading →

by Adam Thierer & Berin Szoka — (Ver. 1.0 — Summer 2009)

by Adam Thierer & Berin Szoka — (Ver. 1.0 — Summer 2009)

We are attempting to articulate the core principles of cyber-libertarianism to provide the public and policymakers with a better understanding of this alternative vision for ordering the affairs of cyberspace. We invite comments and suggestions regarding how we should refine and build-out this outline. We hope this outline serves as the foundation of a book we eventually want to pen defending what we regard as “Real Internet Freedom.” [Note: Here’s a printer-friendly version, which we also have embedded down below as a Scribd document.]

I. What is Cyber-Libertarianism?

Cyber-libertarianism refers to the belief that individuals—acting in whatever capacity they choose (as citizens, consumers, companies, or collectives)—should be at liberty to pursue their own tastes and interests online.

Generally speaking, the cyber-libertarian’s motto is “Live & Let Live” and “Hands Off the Internet!” The cyber-libertarian aims to minimize the scope of state coercion in solving social and economic problems and looks instead to voluntary solutions and mutual consent-based arrangements.

Cyber-libertarians believe true “Internet freedom” is freedom from state action; not freedom for the State to reorder our affairs to supposedly make certain people or groups better off or to improve some amorphous “public interest”—an all-to convenient facade behind which unaccountable elites can impose their will on the rest of us.

Continue reading →

One reason AT&T may not like Google Voice is that it allows you to send and receive text messages for free. This has led many to argue that SMS are free to the carriers and they are overcharging. Congress is considering getting involved. Most recently there’s this from David Pogue in the NY Times:

The whole thing is especially galling since text messages are pure profit for the cell carriers. Text messaging itself was invented when a researcher found “free capacity on the system” in an underused secondary cellphone channel: http://bit.ly/QxtBt. They may cost you and the recipient 20 cents each, but they cost the carriers pretty much zip.

The price of a text message does sound ridiculous when you consider it on a per bit basis. The problem with thinking about it that way, though, is that it neglects the fact that AT&T had to build a network, and it has to maintain that network, before a text message can be “free.” AT&T charges customers so it can recoup its investment. It does so through voice and data service fees, but also through other fees, including for text messages. However it charges customers, it ultimately has to bring in enough to cover its costs or it goes out of business.

Now, if we passed a law today that said carriers could not charge for SMS because, after all, it’s free, we would see a an increase in the fees it charges for voice, data, and other services. The mix of prices for services we have right now is one the market will bear and consumers want, and there’s no reason to think that we could command a better one.

Better yet, if you want a “free” text messaging option, consider Boost Mobile, which offers just that. Of course, they have different voice prices and an older and slower network. In the end, they have to cover their costs, too.

Over at Twitter, our TLF blogging colleague Jerry Brito asks a smart question about the Federal Communications Commission’s recently-opened investigation of the Apple-Google spat over Apple’s recent decision to reject the Google Voice app from the iPhone App Store. Jerry asks: “Maybe I should know this, but what authority does the FCC have to demand that Apple explain anything?” Good question, Jerry! But no, I don’t think there’s anything you’re missing. We might consider this merely the latest chapter of the agency’s rogue operator history: If you can’t find the authority to do something, just assert it anyway and go for broke! The idea of living within the confines of the law and paying attention to statutory authority seems like an alien concept to the FCC. As my PFF colleagues Barbara Esbin and Adam Marcus have pointed out in their amazing recent law review article, “The Law Is Whatever the Nobles Do: Undue Process at the FCC,” when all else fails, the agency just asserts “ancillary jurisdiction” and claims that the whole world is their oyster. They argue:

The FCC’s means of asserting regulatory authority over broadband Internet service providers’ (“ISP”) network management practices is unprecedented, sweeping in its breadth, and seemingly unbounded by conventional rules of interpretation and procedure. We should all be concerned, for apparently what we have on our hands is a runaway agency, unconstrained in its vision of its powers.

Of course, even if we ignore the agency’s cavalier attitude about the law and statutory authority, there are other reasons to be concerned about FCC interference in this matter. Continue reading →

providers next month if Federal Communications Commission Chairman Julius Genachowski gets his way. In a milestone speech on Monday, Genachowski proposed sweeping new regulations that would give the FCC the formal authority to dictate application and network management practices to companies that offer Internet access, including wireless carriers like AT&T and Verizon Wireless.

providers next month if Federal Communications Commission Chairman Julius Genachowski gets his way. In a milestone speech on Monday, Genachowski proposed sweeping new regulations that would give the FCC the formal authority to dictate application and network management practices to companies that offer Internet access, including wireless carriers like AT&T and Verizon Wireless.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.