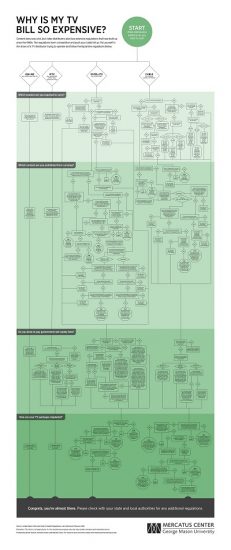

In the US there is a tangle of communications laws that were added over decades by Congress as–one-by-one–broadcast, cable, and satellite technologies transformed the TV marketplace. The primary TV laws are from 1976, 1984, and 1992, though Congress creates minor patches when the marketplace changes and commercial negotiations start to unravel.

Congress, to its great credit, largely has left alone Internet-based TV (namely, IPTV and vMVPDs) which has created a novel “problem”–too much TV. Internet-based TV, however, for years has put stress on the kludge-y legacy legal system we have, particularly the impenetrable mix of communications and copyright laws that regulates broadcast TV distribution.

Internet-based TV does two things–it undermines the current system with regulatory arbitrage but also shows how tons of diverse TV programming can be distributed to millions of households without Congress (and the FCC and the Copyright Office) injecting politics into the TV marketplace.

Locast TV is the latest Internet-based TV distributor to threaten to unravel parts the current system. In July, broadcast programmers sued Locast (its founder, David Goodfriend) and in September, Locast filed its own suit against the broadcast programmers.

Many readers will remember the 2014 Aereo decision from the Supreme Court. Much like Aereo, Locast TV captures free broadcast TV signals in the markets it operates and transmits the programming via the Internet to viewers in that market. That said, Locast isn’t Aereo.

Aereo’s position was that it could relay broadcast signals without paying broadcasters because it wasn’t a “cable company” (a critical category in copyright law). The majority of the Supreme Court disagreed; Aereo closed up shop.

Locast has a different position: it says it can relay broadcast signals without paying because it is a nonprofit.

It’s a plausible argument. Federal copyright law has a carveout allowing “nonprofit organizations” to relay broadcast signals without payment so long as the nonprofit operates “without any purpose of direct or indirect commercial advantage.”

The broadcasters are focusing on this latter provision, that any nonprofit taking advantage of the carveout mustn’t have commercial purpose. David Goodfriend, the Locast founder, is a lawyer and professor who, apparently, sought to abide by the law. However, the broadcasters argue, his past employment and commercial ties to pay-TV companies mean that the nonprofit is operating for commercial advantage.

It’s hard to say how a court will rule. Assuming a court takes up the major issues, judges will have to decide what “indirect commercial advantage” means. That’s a fact-intensive inquiry. The broadcasters will likely search for hot docs or other evidence that Locast is not a “real” nonprofit. Whatever the facts are, Locast’s arbitrage of the existing regulations is one that could be replicated.

Nobody likes the existing legacy TV regulation system: Broadcasters dislike being subject to compulsory licenses; Cable and satellite operators dislike being forced to carry some broadcast TV and to pay for a bizarre “retransmission” right. Copyright holders are largely sidelined in these artificial commercial negotiations. Wholesale reform–so that programming negotiations look more like the free-market world of Netflix and Hulu programming–would mean every party has give up something they like improve the overall system.

The Internet’s effect on traditional providers’ market share has been modest to date, but hopefully Congress will anticipate the changing marketplace before regulatory distortions become intolerable.

Additional reading: Adam Thierer & Brent Skorup, Video Marketplace Regulation: A Primer on the History of Television Regulation and Current Legislative Proposals (2014).

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.