I’ve been wading through the FCC’s latest Mobile Wireless Competition Report, and articles about it trying to make sense of what the the agency might be up to on this front. It’s hard to get a read on where the agency may be going here. As my PFF colleague Mike Wendy suggested in his post on the FCC’s report, “far from press reports which state the FCC clearly determined the market is not ‘effectively competitive,’ well, that’s wrong. In fact, the FCC fails to make any such determination whatsoever.” Moreover, just flipping through the charts and tables of the 237-page report, one is struck by how dynamic this marketplace is, and how crazy it would be for the FCC to declare it anything other than effectively competitive and highly innovative.

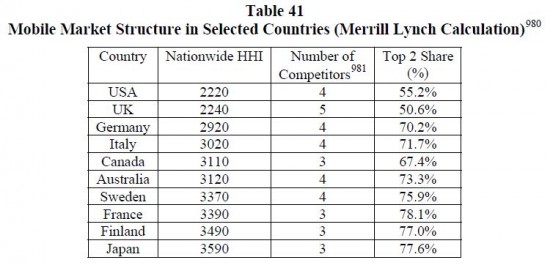

Yet, the FCC and many others seem hung up on industry structure. In particular, there seems to be a lot of hand-wringing about increasing consolidation among the sector’s top players. But the data the FCC reproduces in the report seem to undermine that concern. For example, here’s a snapshot of the “Mobile Market Structure in Selected Countries,” which appears on pg. 197 of the FCC report. It shows how much more consolidated foreign mobile markets are relative to the U.S., which is true of wireline markets too. And you can find much more evidence of how competitive the marketplace is in these two reports.

Nonetheless, it is still they case that the mobile marketplace is experiencing more consolidation these days. It’s nothing to fret about, however. The sky isn’t about to fall on consumers as some seemingly fear. The problem with this “big-is-bad” thinking is that it fails to understand the nature of competition in network industries. The economics of network industries are not those of a corner lemonade stand. We’re never going to have hundreds or even dozens of companies providing the underlying backbone over which bits of information travel. There are significant sunk costs associated with providing network services. Deploying all these network alone is a nightmare. Rolling out a sophisticated and reliable wireless architecture is incredibly costly and labor-intensive. Just siting all the towers, for example, can be cumbersome and get quite expensive. And then there are the endless “truck rolls” to fix tiny problems and upgrade facilities.

The bottom line is this: The networking business is for big boys, and there are only going to be so many big boys that will ever be able to stick with it and turn a profit to keep those networks functioning properly while also planning for future innovations and upgrades. We learned this lesson the hard way in the late 1990s as we witnessed the FCC conduct a grand experiment with infrastructure sharing in an effort to create more competition in the telecom business. The idea was simple: Let’s provide small telecom resellers every possible incentive to use the networks owned by incumbent telecom companies so we can create a new crop of “competitors.” It was obvious that this scheme was never going to produce any legitimate new network competitors, but what was so interesting about this misguided episode in regulatory planning was that it didn’t even produce any reliable “fake” competitors either. The resellers that were given access to existing networks were never able to concoct a legitimate business model to convince investors (or even that many customers) that they were worthwhile investments. These resellers create networks built of paper instead of serious, facilities-based networks. As a result, almost all of them went under. Again, the hard lesson here was that the networking business is not a Mom-and-Pop operation.

THIS IS NOT TO SAY THAT THE NETWORKING BUSINESS IS A NATURAL MONOPOLY. Indeed, from everything we know today, we can safely conclude that the wireless world and broadband networking business can be very competitive with even just a couple of major providers in each region. When it comes to wireless, we’re damn lucky to have 4 or more providers in many regions today. I still find it astonishing we have as many wireless providers as we do. Still, many will claim that’s just not enough. We need more networks to have “real” competition, they will say. But, again, the economics of networking will simply not allow it. There is just no way that more than a few providers will be able to remain profitable in direct competition with each other. To amortize the sunk costs of network deployment, maintenance and upgrades, carriers need to have a steady base of customers and fairly reliable rate of return on their investments. Nobody has put it better in recent memory than the current Obama administration Department of Justice when the agency’s leading officials noted in a filing to the FCC:

In markets such as this, with differentiated products subject to large economies of scale (relative to the size of the market), the Department does not expect to see a large number of suppliers. Nor do we expect prices to be equated with incremental costs. If they were, suppliers could not earn a normal, risk-adjusted rate of return on their investments in R&D and infrastructure.

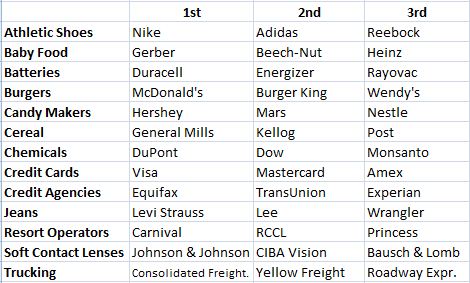

Exactly right. Moreover, almost every mature industry usually shakes out to just a handful of providers. If you don’t believe me, check out The Rule of Three: Surviving and Thriving in Competitive Markets by Jagdish Sheth and Rajendra Sisodia. It’s a few years old now, but it remains the best explanation I’ve seen of how things typically play out in most markets. The following table is a bit dated, but here’s a snapshot of the “big 3” in many other major industry sectors:

If we can live with 3 or 4 players in markets such as these, we’ll be just fine with just 3 or 4 major backbone providers or wireless operators. And if we expect major wireless players to make the investments necessary to support the robust, nationwide, high-speed networks that we will need to have invented and then reinvented every couple of years, then we must allow them to have the assets and scale necessary to thrive going forward. Lemonade stand economics can work for corner coffee shops and shoe shines, not for sophisticated wireless networks.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.