Recently, the Future of Life Institute released an open letter that included some computer science luminaries and others calling for a 6-month “pause” on the deployment and research of “giant” artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. Eliezer Yudkowsky, a prominent AI ethicist, then made news by arguing that the “pause” letter did not go far enough and he proposed that governments consider “airstrikes” against data processing centers, or even be open to the use of nuclear weapons. This is, of course, quite insane. Yet, this is the state of the things today as a AI technopanic seems to growing faster than any of the technopanic that I’ve covered in my 31 years in the field of tech policy—and I have covered a lot of them.

In a new joint essay co-authored with Brent Orrell of the American Enterprise Institute and Chris Messerole of Brookings, we argue that “the ‘pause’ we are most in need of is one on dystopian AI thinking.” The three of us recently served on a blue-ribbon Commission on Artificial Intelligence Competitiveness, Inclusion, and Innovation, an independent effort assembled by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. In our essay, we note how:

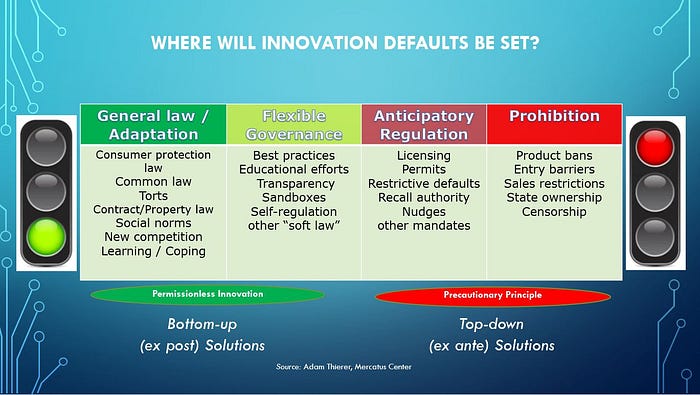

Many of these breakthroughs and applications will already take years to work their way through the traditional lifecycle of development, deployment, and adoption and can likely be managed through legal and regulatory systems that are already in place. Civil rights laws, consumer protection regulations, agency recall authority for defective products, and targeted sectoral regulations already govern algorithmic systems, creating enforcement avenues through our courts and by common law standards allowing for development of new regulatory tools that can be developed as actual, rather than anticipated, problems arise.

“Instead of freezing AI we should leverage the legal, regulatory, and informal tools at hand to manage existing and emerging risks while fashioning new tools to respond to new vulnerabilities,” we conclude. Also on the pause idea, it’s worth checking out this excellent essay from Bloomberg Opinion editors on why “An AI ‘Pause’ Would Be a Disaster for Innovation.”

The problem is not with the “pause” per se. Even if the signatories could somehow enforce a worldwide stop-work order, six months probably wouldn’t do much to halt advances in AI. If a brief and partial moratorium draws attention to the need to think seriously about AI safety, it’s hard to see much harm. Unfortunately, a pause seems likely to evolve into a more generalized opposition to progress.

The editors continue on to rightly note:

This is a formula for outright stagnation. No one can ever be fully confident that a given technology or application will only have positive effects. The history of innovation is one of trial and error, risk and reward. One reason why the US leads the world in digital technology — why it’s home to virtually all the biggest tech platforms — is that it did not preemptively constrain the industry with well-meaning but dubious regulation. It’s no accident that all the leading AI efforts are American too.

That is 100% right, and I appreciate the Bloomberg editors linking to my latest study on AI governance when they made this point. In this new R Street Institute study, I explain why “Getting AI Innovation Culture Right,” is essential to make sure we can enjoy the many benefits that algorithmic systems offer, while also staying competitive in the global race for competitive advantage in this space. Continue reading →

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

Running List of My Research on AI, ML & Robotics Policy

by Adam Thierer on July 29, 2022 · 0 comments

[last updated 4/24/2024]

This a running list of all the essays and reports I’ve already rolled out on the governance of artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and robotics. Why have I decided to spend so much time on this issue? Because this will become the most important technological revolution of our lifetimes. Every segment of the economy will be touched in some fashion by AI, ML, robotics, and the power of computational science. It should be equally clear that public policy will be radically transformed along the way.

Eventually, all policy will involve AI policy and computational considerations. As AI “eats the world,” it eats the world of public policy along with it. The stakes here are profound for individuals, economies, and nations. As a result, AI policy will be the most important technology policy fight of the next decade, and perhaps next quarter century. Those who are passionate about the freedom to innovate need to prepare to meet the challenge as proposals to regulate AI proliferate.

There are many socio-technical concerns surrounding algorithmic systems that deserve serious consideration and appropriate governance steps to ensure that these systems are beneficial to society. However, there is an equally compelling public interest in ensuring that AI innovations are developed and made widely available to help improve human well-being across many dimensions. And that’s the case that I’ll be dedicating my life to making in coming years.

Here’s the list of what I’ve done so far. I will continue to update this as new material is released: Continue reading →