Perfect media equality is impossible. There has never been anything close to “equal outcomes” when it comes to the distribution or relative success of old media: books, magazines, music, movies, book, theater tickets, etc. A small handful of titles have always dominated, usually according to a classic “power law” or “80-20? distribution, with roughly 20% of the titles getting 80% of the traffic / revenue.

Perfect media equality is impossible. There has never been anything close to “equal outcomes” when it comes to the distribution or relative success of old media: books, magazines, music, movies, book, theater tickets, etc. A small handful of titles have always dominated, usually according to a classic “power law” or “80-20? distribution, with roughly 20% of the titles getting 80% of the traffic / revenue.

But here’s the really interesting thing: This trend is increasing, not decreasing, for newer and more “democratic” online media. As I pointed out in two previous essays [“YouTube, Power Laws & the Persistence of Media Inequality” & “Cuban on Fragmentation & Attention in the Blogosphere (or Why Power Laws Really Do Govern All Media)”], there is solid evidence that blogs, YouTube, Twitter, and other digital media outlets and platforms not only follow a classic power law distribution but that the distribution is even more heavily skewed toward the “fat head” of the distribution curve, not “the long tail” of it.

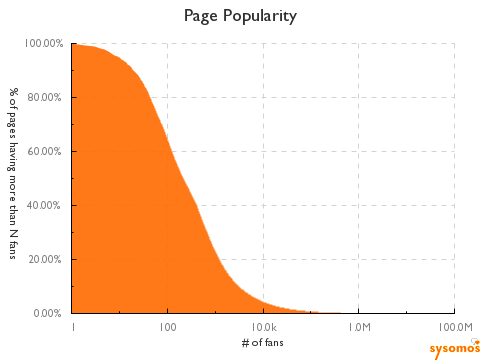

The latest evidence of the persistence of power laws across media comes from Facebook. Erick Schonfeld has a new essay up at TechCrunch (“It’s Not Easy Being Popular. 77 Percent Of Facebook Fan Pages Have Under 1,000 Fans“) highlighting some new findings from an upcoming report by Sysomos, a social media monitoring and analytics firm. Here’s the summary from Schonfeld:

A full 77 percent of Facebook fan pages have less than 1,000 fans… The vast bulk of fan pages have between 10 and 1,000 fans. Only 4 percent have more than 10,000 fans, and less than 1/20th of a percent have more than a million fans. It breaks down as follows:

- 95% of pages have more than 10 fans

- 65% of pages have more than 100 fans

- 23% of pages have more than 1,000 fans

- 4% of pages have more than 10,000 fans

- 0.76% of pages have more than 100,000 fans

- 0.047% of pages have more than one million fans (297 in total).

That’s a pretty lopsided distribution but, again, it’s the same sort of thing we’ve seen at work for all media platforms. But this distributional inequality has been accelerating and deepening with the Internet and digital media distribution platforms. As Schonfeld rightly summarizes, “The Internet has long been defining celebrity down, and now we know by how much.” Exactly right, but down below I’ll explain why shouldn’t get too worked up about all this.

First, let’s try to understand why this is occurring. Simply put, freedom of choice breeds media inequality through a radically uneven distribution of outcomes. Historically, some media economists and analysts thought that power laws always exist in all media contexts because the economics of media are quite different than most other industries. Namely, media industries typically exhibit “public good” qualities; high fixed (production costs), but lower distribution costs. But then along came the Internet–a perfectly open media platform for all to use as they wish–and yet power law not only did not fade, but the distributional imbalance became more severe, as Clay Shirky first documented here.

So, there must be another explanation. I believe the primary reason why power laws are probably more prevalent in media and communications industries than in other sectors of the economy is because the creation and consumption of news and popular culture is a truly social phenomenon. Think of it as the economics of popular choice and the sociology of fashion and fads. People (and consumers) react to what others are reading or watching. Word-of-mouth counts. Bandwagon effects exist. First-mover advantages are significant. And so on. The end result is a hopeless imbalance of outcomes or outputs. Media egalitarianism is simply an impossibility. And, again, despite what Chris Anderson said in The Long Tail, the “future of all business” most definitely does not lie mostly in the 80% part of the tail. While the long tail of the curve certainly is more profitable than in the past, that “fat head” of the tail is still where most profits (or at least eyeballs) are at.

But as I argued here previously, none of this makes a damn bit of difference!

What is really important is equality of media opportunity, not equality of media outcomes. A focus on the latter is both foolish and destructive. It is foolish because media equality is an impossibility absent extreme measures, which in turn explains why it is destructive. We would need totalitarian government controls on media outputs and consumption in order to achieve anything remotely close to “balance” or “equality” in terms of media results.

Again, all that really counts is that people have a chance to be heard, not whether millions are listening. New media platforms really do change some things for the better because at least we now all have an equal chance to make a go at it and grab a bit of that audience. That’s certainly more than could be said back in the old analog media world, in which we suffered from outlet scarcity and information poverty. Today, by contrast, will live in a wonderful world of media abundance, where every man, woman, and child really does have a soapbox on which to stand and speak to the world.

Of course, no one may be listening. And there will always be someone else who will nab greater audience share than you.

Get used to it. It is the way the media world has always worked, and it is the way every media platform will work until the end of time. So long as citizens are free to choose, media inequality is inevitable.

[Update May 2015: Guess what, this is true for Twitter, too!]

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.

The Technology Liberation Front is the tech policy blog dedicated to keeping politicians' hands off the 'net and everything else related to technology.